France riots: How the country's police and political elites protect each other

For clinical (and cynical) reasons worth investigating, French political elites have been reenacting a disturbing narrative, which frames their relationship with the people they're supposed to lead, for over two centuries.

In this nightmare vision, a horde of angry people raid the mansions and ministries of the republic (or the king, or the emperor), claiming the heads of their leaders and parading them on sticks.

And the only hope they can rely on, the only force they can count on to save them… is the police.

The "forces of order", as they are referred to in France, strive to protect their order, as a power structure of domination operating in two dimensions.

The first dimension is social and economic, maintaining privileges where they belong: yesterday for the benefit of the nobles and bourgeois; today at the service of major corporate and capitalistic interests.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The second is racial and political, building on the legacy of stereotypes and structural discrimination inherited from the French colonial empire.

In both dimensions, the police are there to implement the government's political vision: they curb the demonstrations, guard the banks, criminalise political opponents, harass Arab and Black kids at a disproportional rate and, on occasion, kill them.

Police brutality

This is why, on the night of 17 October 1961, the police killed hundreds of Algerian demonstrators by throwing them into the Seine.

This is why, on 29 November 1972, the police shot Mohammed Diab in the chest and back after beating him, while his mother and his sister watched the whole scene from the window.

This is why, on 16 October 1984, the police shot Salim Bazari in his car after he went through a red light.

This is why, on 6 December 1986, the police beat Malik Oussekine to death, when he was just walking in Paris after a jazz concert.

This is why, on 6 April 1993, the police killed 17-year-old Makome M'Bowole at a Paris police station, by shooting him at point blank range.

This is why, on 27 October 2005, Zyed Benna, 17, and Bouna Traore, 15, were running for their lives in a Paris suburb, terrified of the police, eventually killed by being electrocuted in a power substation, although they had done nothing wrong.

This is why Adama Traore died in police custody in July 2016, before his siblings were almost systematically criminalised, harassed and ostracised for calling for the truth about Traore's death.

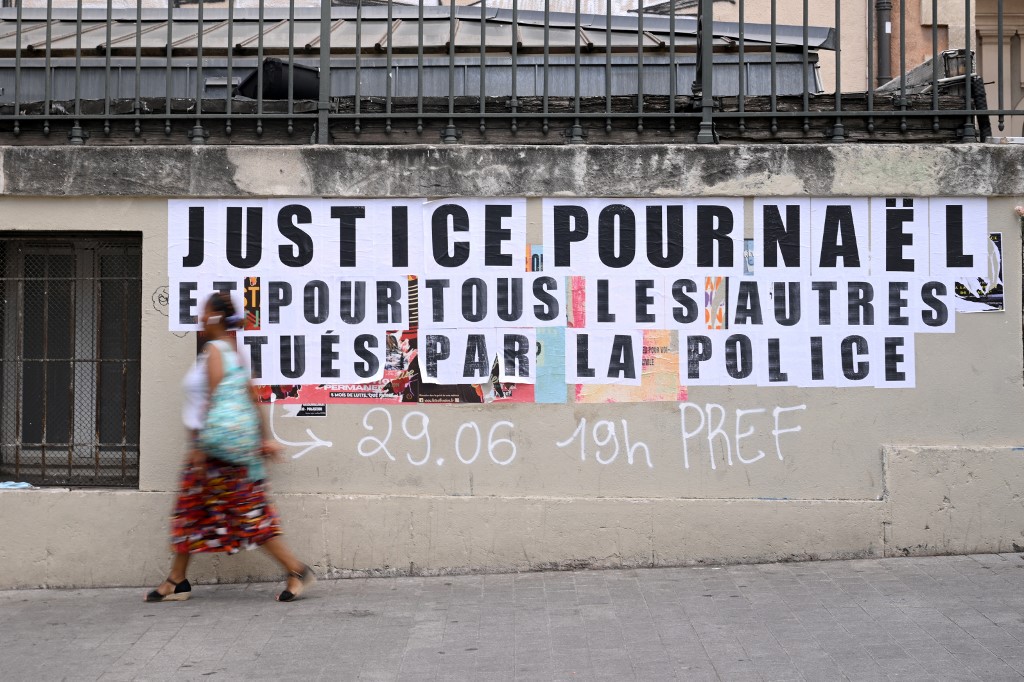

And this is why, on 27 June 2023, in Nanterre, a Paris suburb, 17-year-old Nahel Merzouk was shot and killed at point-blank range, like hundreds of other young men before him.

Many of these deaths reveal a racial bias in the way young Black and Arab men are constructed as a security threat to France, but it is important to point out that they are not the only targets of police violence.

Cedric Chouviat, for instance, a 42-year-old delivery man, died of asphyxia and a broken larynx at the hands of the police after using his cell phone on his scooter, in January 2020. In October 2014, Remi Fraisse, a 21-year-old botanist, was killed by a grenade fired by the police. And in June 2019, Steve Maia Canico was found dead in the River Loire, after police had raided the concert in Nantes he was attending.

Structural factors

The dynamics vary, but some structural factors remain at play: Firstly, Black and Arab kids are constructed as a threat, inherited from post-colonial racist tropes, and disproportionately targeted by the police.

A study has shown that Black male youths have a six times greater chance of being stopped by the police than white males, and Arab youths an eight times greater chance.

Secondly, the security approach implemented by the French police towards Black and Arab young men is deeply rooted in the political structures of the country and warrants unsolicited and unjustifiable violence, leading, on hundreds of occasions, to death.

Third, this racially biased approach focused on Black, Arab, Muslim and migrant communities acts as a laboratory, which in turn informs and influences the way security is implemented at a much wider level, affecting the fundamental freedoms and safety of all citizens.

The security approach implemented by the police towards Black and Arab young men is deeply rooted in the political structures of the country and warrants unsolicited violence

Fourthly, more than half of the police force votes for the far right and now, through their unions and representatives, uses lobbying techniques and threats to advance their political agenda, furthering even more the divide between the general population and the very institution whose mission is to protect them.

Lastly, the office in charge of investigating police violence and abuses (IGPN) is made up of police officers, resulting in a dismal number of cases actually looked at, with almost no sanctions, resulting in a total absence of trust in the institution and its accountability.

As long as the French government does not hold the police accountable when they break the laws they are supposed to enforce and the values they are supposed to uphold, no change can be expected in the foreseeable future.

Political elites in the country will continue to maintain this toxic relationship with the police, whereby they protect each other while endangering the security of all.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.