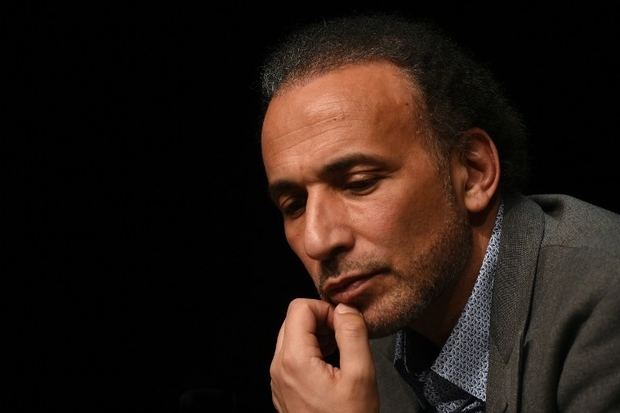

INTERVIEW: Tariq Ramadan on political Islam's 'necessary crisis'

Sometimes seen as an Islamic scholar, a theologian or even a preacher, Tariq Ramadan is first and foremost a philosopher who intends to connect political and religious matters. Annoying for some, a pioneer for others, everyone has an opinion about him. He is the author of books such as Islam and the Arab Awakening (2011) and What is a Western/Muslim Individual Today (2015).

Tariq Ramadan talks to Middle East Eye about terrorism, political Islam and what is going on in the Middle East and in France, where he recently applied for citizenship:

MEE: Does terrorism as we know it today bring up the issue of the interpretation and reform of Islam or is it only a social matter? In other words, according to this ongoing debate between Olivier Roy and Gilles Kepel, does it mean that we are seeing the “Islamisation of radicalism” (Roy) or “is Islam becoming more radicalised”?

Tariq Ramadan: I do believe that none of them is a hundred percent right. We need to acknowledge that there is a real issue with how the Scriptures are being interpreted. Whenever I am told that terrorists are not Muslim, I systematically reply that they actually are, and they cannot be marginalised, the same way they are marginalising other Muslim people. Scriptures are quoted even though their interpretations are twisted. In the face of misinterpretation the only way out would be using another interpretation of the Scriptures.

Moreover, those young ones who want to try military jihad are facing a triple issue. First of all, they are missing the point when it comes to understanding what there is at stake from a political viewpoint. How come so many of them are going to Syria and so few to Palestine, even though, when it comes to symbolism, Palestine definitively wins.

Then, it is essential to understand that it is not a religious matter. Among the UK Task Force, set up after the London bombing in 2005, it had been observed that 92 percent (now 87 percent according to the statistics) of the people who were leaving for jihad, became “radicalised” or I would rather say “extremely violent,” within six months. When they are planning the attacks, they are living a very sketchy life. However, saying that all of them have social difficulties would be untrue. Some of them feel humiliated, others frustrated. Sometimes, we would have extreme psychologically fragile cases. In the US, some of them got enrolled because they were in debt or threatened.

Finally, let’s not forget about the recruiters behind their screens. Those ones are quite skillful and well-supported financially. We came across the testimony of two young girls who explained to us how those recruiters take the time to exploit any psychological fragility they might spot in the future recruits. For instance, one of those young girls’ best friend from growing up got killed in Syria. Then, she was talked into going to Syria herself, so she could restore her late best friend’s dignity. This death laid the groundwork for her religious belief.

MEE: Is there an issue with the use of the word “Islamism”, since it covers up a wide range of meanings, from being applied to Ennahda, the Tunisian political party, to describing the takfiri movement?

TR: Yes, things need to be properly named. Political confusion starts with terminology confusion. Islamism implies some sort of political and social plan for Muslim people. In that classification, we find different categories. Legalist ones, traditional ones and revolutionary ones. Some of them are revolutionary but are non-violent, others are extremely violent. There are also the ones we call the literalists, like the Egyptian party Hizb al-Nour that used to be against democracy and now is getting into the political game.

Saying that the origin of the Islamic State (IS) is within the Muslim Brotherhood organisation only strengthens IS. This is what the Israeli government asserts when claiming that Hamas and IS are the exact same thing. By saying so, the historical resistance [against the Israeli occupation] is viewed as unlawful, called extremism and terrorism.

MEE: How are European Muslims supposed to answer all the questions those attacks have brought forward? Are they supposed to say sorry, as they are urged to do, or should they dissociate themselves clearly through getting even more politically involved?

TR: If we agree to say that those terrorists are indeed Muslim, I have no problem whatsoever to condemn their actions. I won’t apologise though, or justify my point of view. Condemning is essential in order to start a constructive discussion, in order to introduce an “and” that leads to reflection: “I condemn those actions and …’.

You cannot limit the debate to being solely in favour or against. It should be more complex. When you condemn, you need to understand what led to it. In general, if it is our responsibility to condemn terrorist actions after they had happened, we have an even greater responsibility beforehand to make sure they won’t happen. When Manuel Valls says there’s nothing to understand because “understanding is justifying,” he echoes back to Georges W Bush’s logic in 2001. When François Hollande says “they are attacking us because of who we are,” what does it say about victims in Mali, Baghdad, Ivory Coast or Turkey?

MEE: What does IS truly stand for? Is it only threatening our safety?

TR: Do you really think this organisation has settled in Iraq and Syria by chance? Those organisations, al-Qaeda being the first one, have all settled in areas full of mining and oil resources or in geostrategic zones. They settled in Afghanistan which underground is filled with oil and lithium. North Mali is filled with mining resources (uranium).

Moreover, it is essential to question the impact and role of some international players that create or let those organisations settle there. Thus, IS has played a major role in helping Bashar al-Assad to reposition Syria on the international scene. Now, it is almost impossible to come up with a solution that would exclude him. The political game appears to be very cynical indeed.

Then, the fact that this organisation is called the Islamic State reveals something even deeper. In fact, it implies that every single Islamist party in Egypt, Iraq or Tunisia are not really representing Islam and Muslim people. Nowadays, political Islam is going through a crisis, however this crisis is necessary, for it will lead to a changing way of thinking. In order to make it out of this dead-end, reviewing political Islam becomes mandatory.

Muslim societies must leave behind these dual aspects: secularism/Islamism. During the Arab Spring in 2011, I had been thinking that what was happening was the sign of the loss of political meaning for Arab societies. This is actually what has happened …

MEE: Precisely how do you assess the political landscape in the Middle East since the 2011 Arab Spring? For instance in Egypt, how does President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s politics differ from Mubarak’s?

TR: In my opinion, we had qualified those actions as “revolutionary” too quickly. Back then, I was cautiously optimistic. I reckoned we were dwelling too much on political issues and didn’t take into consideration what was at stake economically. For instance, we can affirm that what happened in Egypt was an internal military coup d’etat. The corrupted governance of Mubarak and his son Gamal became an issue. Moreover, he had started to negotiate more openly with China and India.

Then more broadly, a destabilised Middle East in pursuit of security means that the US has found its way back in. When it comes to economic relationships, China and India are doing a far better job. Shaking up this whole region means that Israel needs the US for its safety and military camps are “flourishing” everywhere in the Middle East. It has been said that Obama is less interested in the Middle East. I don’t think so. This mess has been created and maintained. Maybe the US is pretending to be less interested, however, it allows them to take their power back when it comes to security.

MEE: How can we justify people’s different reactions regarding the victims of terrorism in Paris and Brussels versus the victims in Baghdad or Beirut?

TR: Globalisation means indeed everything is global but there are still very specific centres of power, especially when it comes to media and news. Those media hubs are located in the “North,” so the media’s exposure and how events are going to be covered will definitely differ from whether or not those attacks are happening in the “North” or not. Misinformation about some attacks is going to affect how emotionally involved the audience is going to get. In the end, an emotional ranking is artificially created when it comes to casualties.

When terrorism is directly aiming at Western countries, it is automatically and abnormally enlarged in order to instill emotions and fear. However, when attacks happen in the Middle East, is it conveniently downplayed and less talked about. Unless they would benefit more from a heavy coverage.

MEE: You just gave a conference in Bordeaux; Alain Juppe, mayor of Bordeaux and probably running for president in 2017, said he was against it. He brought forward the usual argument that “you are talking out of both sides of your mouth”. What do those controversies around you say about France?

TR: This is old news indeed, using the same tricks. A topic can be distorted. It is like using a smoke screen, the same thing for an individual. The topic here is Islam. If French politicians are no longer talking about Islam, they know they will have to talk about something else, which brings the spotlight on their inefficiency. They will have to talk about domestic social and economic issues and they will have to justify their foreign policy, which is obviously something they need to avoid at all costs.

Saying that I am talking out of both sides of my mouth just proves my very point. Politicians would bypass real social issues by referring to my grandfather, who founded the Muslim Brotherhood, or to my brother, currently chairman of the Islamic Centre in Geneva.

I can't help but notice that those feuds from French politicians against me would suddenly reappear before elections. I am portrayed as a dangerous individual who can be fought thanks to their ideas. In my opinion, those manoeuvres are serious political mistakes. How can someone like Alain Juppé still claim I haven’t condemned the Paris and Brussels attacks, when I actually have. What I am saying is crystal clear.

Those politicians need to finally understand that the votes of French Muslim people are as important as anybody else. In 2012, those French Muslim people voted massively for Francois Hollande against Nicolas Sarkozy. With the results of elections getting even tighter, those votes can make the difference. I am obviously not in favour of a “community electorate,” however, pressure is so great on them that I can easily understand how it can affect their votes.

MEE: You did claim before the Paris attacks that there is no racism or Islamophobia in France, it is only fear. Do you still believe that?

TR: Yes I do. I think that political parties are fuelling this fear in order to create divisions. The more we bring up fear, the more we neglect real political issues. Political debate in France is crumbling since every single issue is brought to Islam now. By doing so, fear is created which can lead to racism. However, we can overcome that fear through trust.

Part of the French political class is realising that there is are large number of Muslim people coming from the ghettos who want to make themselves heard, politically, especially about foreign policy issues. Its electoral weight can bring back to the forefront the Palestinian issue.

MEE: What made you apply for French citizenship last February?

TR: For the past 25 years, I have refused to apply for it. I had no intention to cover my tracks since I am not a politician and I do not represent anybody. However, I have noticed I have always been put aside. Moreover, lately we have talked about revoking French citizenship for some individuals. Therefore, I have decided to apply for citizenship, which in a way points out the contradictions of this bill that states the forfeiture of French citizenship exclusively to individuals holding dual nationalities. Through this application, I put myself in the midst of the French political debate and discredit everything that might be said against me about this matter.

Nevertheless, I have no political agenda whatsoever, even though some might think the contrary.

This interview was translated from MEE French by Nassima Demiche.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.