The parents treated as terrorists for trying to save their son

From outside, the entrance looked unpromising: a nondescript grey door tucked behind a supermarket and a mosque on a traffic-choked high street in east London. But inside the welcome could not have been warmer.

For Sally Lane and John Letts, the journey of a few hours from their home in Oxford was as nothing compared to the months of parental angst they had endured since learning that their teenage son, Jack Letts, had travelled, as his mother wrote to a friend, to the “worst possible place”.

And now finally, they felt, they had found the man they had been looking for.

“They were so friendly. They kept hugging us,” Letts told Middle East Eye.

Letts and Lane speak with simmering bemusement that occasionally swells into teary-eyed anger as they describe how their lives have unravelled since that first meeting on 4 November 2015.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“They told us, 'You are a part of our family,'” said Lane. “I honestly thought they were the answer to all our problems."

Lane, 57 with shoulder-length blonde hair, has a sharp memory for the details of the case which she recalls with a precision perhaps honed in her former career as a literary editor. She is wearing the same colourful patterned scarf that she wore when the couple appeared at London's Old Bailey court to face terrorism charges in January 2017.

Letts, 59, with grown-out greying stubble and black-framed glasses, has the look of an unkempt university professor after a morning on the allotment.

His Canadian accent remains untamed by his decades in the UK since he took a job at the University Museum of Natural History in Oxford during the early 1990s. There, he built a career as an archaeological botanist and, more lately, as a farmer and purveyor of heritage grains and sourdough bread.

The couple originally met in Canada but Oxford has been their home ever since, with Jack, the eldest of their two sons, born there in 1995.

The university city was a good match for the family, who were politically engaged and supporters of environmental and progressive causes. But their activism was firmly rooted in western liberal democratic values and an instinctive faith in the integrity and decency of public institutions.

“It’s taken me 57 years to become a radical,” said Lane. “That’s what this experience has done to me. I was very middle of the road but now I see the world completely differently.”

This is the story of how a couple described by one judge as “perfectly decent people” became the focus of a major counter-terrorism investigation and were “ferociously prosecuted” - even as the UK was at the highest state of alert following a series of deadly IS attacks in Europe.

It is also a story about “white middle-class liberal types”, as Letts puts it, entering a looking glass world in which that worldview no longer makes sense.

As Letts sums it up: “Once you find yourself on the other side of the fence, and you are considered an enemy of the state, what happens?”

The meeting

The couple’s meeting in east London was with Hanif Qadir, the head of the Active Change Foundation, a youth-focused charity, with a growing reputation in the fields of “preventing violent extremism” and “deradicalisation”.

Over tea and biscuits, they had told Qadir about Jack: his conversion to Islam aged 16 and his restless eagerness to learn more about the religion and culture. He learnt Arabic prodigiously from books and through conversations with Arab university students whom he met at the local mosque.

'I screamed at him, 'How can you be so stupid? What are you doing? You’re going to get beheaded!’'

- Sally Lane, Jack Letts' mother

His parents were supportive. According to them, Jack had struggled with obsessive compulsive disorder, which they believe his religious practice helped him to control.

In May 2014, then aged 18, Jack embarked on what was meant to be a short holiday in Jordan.

From Jordan, he flew to Kuwait, where he told his parents he intended to enrol on a language course. But without their knowledge he then went to Iraq and onto Syria. At some point he married the daughter of a tribal chief from Fallujah, which by then was under the control of Islamic State (IS) militants.

In early September, Jack phoned Lane to tell her that he was in Syria. The conversation lasted about 30 seconds.

“He said ‘Mum, I’m in Syria’. It was a really bad, crackly line,” said Lane.

“I screamed at him, ‘How can you be so stupid? What are you doing? You’re going to get beheaded!’ And then the line went dead.”

Three weeks later, Jack called again, this time from an Iraqi phone number. By then, Lane had been in touch with numerous organisations and mosques and a local Prevent worker to seek advice.

On the face of it, the Active Change Foundation looked like a regular youth club with table tennis and pool tables, video games and graffiti art on the walls, but its work was attracting attention in high places.

In 2014, during a speech at the United Nations, US President Barack Obama cited ACF's “#NotInMyName” social media campaign as an example of young British Muslims challenging IS propaganda. ACF's work had also been praised and discreetly supported by the British government through the Prevent programme.

Qadir's credentials were based in part on his own life story. An avuncular British-Pakistani originally from the north of England, with mismatched brown hair and a grey beard, the now-54-year-old had travelled to Afghanistan in 2002 with the intention of fighting against the US-led invasion, according to his own account. But he returned disillusioned to the UK within weeks and set up ACF the following year.

If Lane and Letts hoped that Qadir would hear echoes of his own past mistakes in Jack's journey, then they were quickly reassured.

“He said he sounded like a good kid,” Letts recalled Qadir telling them. Qadir had even talked about Jack working for ACF when he returned to the UK, Letts said.

According to the couple, Qadir then revealed details of his connections with the intelligence services, and suggested that he could help them in their efforts to get Jack out of Syria.

“He told us: ‘We have ways of getting people out,’” said Letts.

Qadir will later dispute many of the details of what was said, including the extent of his connections with the security services. But by the end of that meeting Lane and Letts were convinced Qadir was their son's best hope.

A plan was drawn up: Letts would give Qadir access to both his own and Jack’s Facebook accounts, allowing him to see their private messages and posts.

By the time they made the return journey to Oxford, Lane and Letts felt renewed hope. In an email to Qadir a few days later, Lane wrote that the meeting had been “the first time that we have felt not alone or helpless in this horrible situation”.

But unbeknown to them, counter-terrorism police had also contacted ACF to discuss the couple’s case as part of an investigation into their son.

As part of that investigation, police had assigned a Prevent officer to monitor and report on Lane and Letts under the guise of offering them support. It also involved gathering evidence and intelligence through third parties such as ACF.

Prevent is a strand of the British government’s counter-terrorism strategy, which is directed at those the authorities consider vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism. It has long faced criticism amid complaints that it discriminates against Muslims and is used to gather intelligence on those who cross its radar.

What is the Prevent Strategy?

+ Show - HidePrevent is a programme within the British government's counter-terrorism strategy that aims to “safeguard and support those vulnerable to radicalisation, to stop them from becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism”.

It was publicly launched in the aftermath of the 2005 London bombings and was initially targeted squarely at Muslim communities, prompting continuing complaints of discrimination and concerns that the programme was being used to collect intelligence.

In 2011, Prevent's remit was expanded to cover all forms of extremism, defined by the government as “vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs.”

In 2015, the government introduced the Prevent Duty which requires public sector workers including doctors, teachers and even nursery staff to have “due regard to the need to prevent people being drawn into terrorism”.

A key element of Prevent is Channel, a programme that offers mentoring and support to people assessed to be at risk of becoming terrorists. Prevent referrals of some young children have proved contentious. 114 children under the age of 15 received Channel support in 2017/18.

Criticism of the Prevent Duty includes that it has had a “chilling effect” on free speech in classrooms and universities, and that it has turned public sector workers into informers who are expected to monitor pupils and patients for “signs of radicalisation”. Some critics have said that it may even be counter-productive.

Advocates argue that it is a form of safeguarding that has been effective in identifying and helping troubled individuals. They point to a growing number of far-right referrals as evidence that it is not discriminatory against Muslims.

In January 2019 the government bowed to pressure and announced that it would commission an independent review of Prevent. This was supposed to be completed by August 2020. After being forced to drop its first appointed reviewer, Lord Carlile, over his past advocacy for Prevent, it conceded that the review would be delayed.

In January 2021 it named William Shawcross as reviewer. Shawcross's appointment was also contentious and prompted many organisations to boycott the review. Further delays followed. Shawcross's review, calling for a renewed focus within Prevent on "the Islamist threat", was finally published in February 2023 - and immediately denounced by critics.

Details about the police operation targeting Lane and Letts, which were disclosed during their subsequent trial on terrorism charges, provide more clarity about the overlap between Prevent work and police intelligence-gathering.

Within weeks the couple had been arrested and their son, branded “Jihadi Jack” by a Sunday newspaper, had become the focus of a global media story that they could no longer control, with devastating consequences for their lives.

'A wayward teenager'

On 3 November, one day before she and her husband had visited the Active Change Foundation in London, Sally Lane had been interviewed at home by police and formally cautioned about £233 ($302) which she had sent two months earlier in September, at Jack’s request, to a Syrian friend of his who by then was in Lebanon.

“It's nothing like on the telly,” said Detective Constable Michael Neath of the South East Counter Terrorism Unit (SECTU), according to a transcript of the interview.

“There isn't going to be any banging on the table or raised voices or anything like that, so it's not going to be like The Sweeney. Sorry.”

According to Lane and Letts, the money was primarily sent as a humanitarian gesture. It was intended to help the recipient and his family who they understood to be refugees.

But for Jack's parents, it was also an effort to keep open the tenuous lines of communication with their son who had complained in messages that people in the West did not care for Syrian refugees.

This was something the couple say that the police had encouraged. By then, investigators from Thames Valley Police’s South East Counter Terrorism Unit (SECTU) had visited them several times.

In December 2014, Lane and Letts received a low-key visit from police officers who suggested that they could help each other by sharing information about what Jack was up to.

“We told them everything we knew,” said Lane. “We'll tell them what we know and they'll tell us what they know. That was the deal.”

In March 2015, police officers again visited the couple, this time taking away their computers and phones. Jack was now the subject of a terrorism investigation. The couple were warned not to send any money to Syria: this was partly why, Lane told MEE, she later chose to send money to Lebanon instead.

Yet for Letts and Lane, the evidence of their son’s suspected involvement in terrorism appeared inconclusive. In messages via Facebook and Telegram, he was vague, sometimes talking about training to be a cleric or working as a translator. He appeared to have spent time in a hospital in the company of medical students.

Inconsistencies and contradictions in his messages led Letts and Lane to believe that his accounts were sometimes being accessed and used by others, that his communications were being monitored and that he was not free to speak openly.

What was lacking as far as they were concerned was any proof that Jack was a fighter or a member of IS. They approached academics studying the social media accounts of foreign fighters, who told them that Jack did not appear to be linked to any known networks of combatants.

According to his parents, Jack had also spent some time in an IS prison in Mosul for publicly challenging the group.

'I said he's a kind of wayward teenager, in a sense he's rebelling, but he's also got his mental health thing with OCD and all those other things'

- John Letts, Jack's father

They believe that his father-in-law’s influence as a tribal chief may have afforded him some protection and possibly spared him from, on the one hand, being forced to fight or pledge allegiance to the group, or, on the other hand, being executed as an enemy or suspected spy.

In a later police interview following his arrest, Letts recalled a long conversation he’d had with one of the investigators who had visited him one day on his farm.

“I said he's a kind of wayward teenager, in a sense he's rebelling, but he's also got his mental health thing with OCD and all those other things,” Letts said.

“I remember he said, ‘Well, we have no evidence honestly… We just want him to come back so we can interview him.’”

Towards the end of her interview, Lane mentioned that the couple had reached out for help to an organisation whose work had been profiled in a television documentary broadcast the previous week.

The programme, called “My Son the Jihadi”, told the story of Sally Evans, the mother of a Muslim convert, Thomas Evans, from High Wycombe, who joined al-Shabaab in Somalia and had been killed fighting in Kenya earlier in 2015.

The organisation was the Active Change Foundation, which was shown offering support to Sally Evans as she sought to understand her son’s transformation into an armed militant.

Lane and Letts had not yet watched the programme but they had been told about it and ACF's work. Letts had tried calling ACF several times but the phone was never picked up. On 31 October, he followed up with an email.

Lane’s mention of the programme appeared to catch the attention of one of her interviewers. “To be fair it might be good for you to watch it,” Specialist Case Investigator Kerry Corbett suggested, according to a transcript of the interview.

After the interview was over, Lane says her interviewers again urged her to watch the programme and told her that they could arrange for her to meet Sally Evans.

Later that day, the Active Change Foundation finally returned John Letts' call.

Operation Classbook

Meanwhile, police were putting in place their plan to deploy a Prevent liaison officer to gather evidence and intelligence on Jack Letts and his parents.

On 4 November, the same day that Sally Lane and John Letts met Hanif Qadir, Rachel Mahon, the appointed officer, had emailed the Active Change Foundation to discuss “signposting a family” to the organisation.

Mahon asked ACF to call her so that she could “explain our situation in a little more detail and establish what your criteria is for support work.”

Details about the Letts investigation, which was named Operation Classbook, were revealed in documents disclosed by the police during preparations for the couple’s trial.

Mahon was expected to “build a rapport with the family”. She would then discuss introducing them to Sally Evans and other support groups.

Her role also involved feeding information back to investigators, who she would notify of “any intelligence or evidential opportunities”. In short, Mahon would be both a shoulder for the family to cry on, and the eyes and ears of the police in the family living room.

Mahon was also expected to submit details of any updates provided by Evans or ACF as a “5x5x5 report”, a form used by police to assess the credibility and reliability of information from external intelligence sources.

Micheal Evans, Sally Evans’ son, told MEE that police officers had mentioned the possibility of introducing his mother to someone in a similar situation during visits to the family.

“The police said there might be someone to introduce us to who was going through a similar thing to see if we can help support each other but nothing ever came of it,” said Evans.

“My mum was trying to find someone else because it was a weird thing to be going through.”

Evans said that police had regularly visited his mother before his brother was killed in June 2015.

“We were always very open with the police because we felt like we didn’t have anything to hide. The police always said we will support you as much as we can but the second you send him money is when there will be a problem.”

Lane and Letts said they had discussed meeting Sally Evans but opted not to because they reasoned that her son had been killed and that talking to her about their own experience might cause her further upset.

While the role of police liaison officers is typically understood to involve supporting families caught up in investigations, their main purpose is to “gather evidence and information”, according to the College of Policing, the professional body for police officers in England and Wales.

Tayab Ali of ITN Solicitors, which represented Lane and Letts during their trial, said: “Often police will try to get the confidence of a family by suggesting that they need support through a family liaison officer, but in fact they are another evidence gatherer.

“They are not acting in the legal interests of the defendant, they are part of the investigative mechanism. What they never say is that you need to be legally represented.

“But this framework is designed to mimic that relationship [between lawyer and defendant] when it is well known in intelligence gathering operations that this is not happening.”

'Jack seems to be making plans'

The profile of the Active Change Foundation had been bolstered by the coverage of its work in “My Son the Jihadi” - but the organisation's work had been in the spotlight for the best part of a decade.

In 2006, CNN International had profiled ACF's work, describing Hanif Qadir as being "on the frontline of Britain's battle against terror". The BBC too had covered the organisation favourably in 2014, calling its staff the “foot soldiers of deradicalisation”.

But the project that had brought it most attention, and Obama's approval, was the #NotInMyName social media campaign in the same year. It encouraged young Muslims to speak out against IS, which was then gaining notoriety with a series of horrific propaganda videos showing the beheadings of Western hostages.

In fact, #NotInMyName had been created with the support of Breakthrough Media (now known as Zinc Network), a media company contracted by the Home Office to produce communications campaigns targeting British Muslims.

ACF's links to Prevent and the Home Office were no secret. Annual reports and accounts filed by the organisation list the Home Office among its funders and partners.

'We did have contacts with the security services and the intelligence services, but not to the point where I could call James Bond to go and pick him up'

- Hanif Qadir, Active Change Foundation

While Hanif Qadir was the public face of the organisation, another key figure who would also become involved in the Letts case was Mike Jervis, 55, ACF’s head of strategy and research.

An East Londoner with Guyanese parents, Jervis’s background was in mentoring youngsters, typically from black and ethnic minority backgrounds, caught up in gangs, and supporting families whose children had been led astray or been victims of gang violence.

But, behind the scenes, Qadir and ACF were under scrutiny. In September 2015, Qadir had been suspended from the Home Office's Channel programme, a deradicalisation scheme within Prevent which paired people assessed to have extremist beliefs with mentors.

According to Qadir, the suspension related to an intervention which he had aborted after he became concerned that the young Muslim convert he was working with was faking extremist beliefs in order to take advantage of the support structure that ACF was offering him.

“He didn’t know anything about Islam," Qadir told MEE. “It was just what he’d been watching in YouTube videos on his phone. And in the end, I said, ‘You know what? I can’t take this guy anymore. He’s doing my head in and he’s been playing us along.’”

Though ACF has now closed, Qadir still rents a small office space in its former building in Waltham Forest. As he talks, he sits among piles of plastic bags of second-hand clothes, left there by a neighbourhood Kashmir-focused charity which uses the space as a storeroom.

Qadir’s suspension did not cover the Letts case, he said, because that related to family support and mentoring, rather than a formal Channel assignment.

Qadir said that he had discussed with Jack’s parents a potential best-case scenario, in which he would return to the UK and eventually work for ACF after due process and a successful rehabilitation had taken their course, at their first meeting in November 2015.

But he denies suggesting that ACF could help Jack leave Syria and says that Lane and Letts have exaggerated his claims about his contacts with intelligence services.

Rather, Qadir says, his offer of help was conditional on Jack leaving Syria himself and reaching a British diplomatic office in a neighbouring country (Qadir says he suggested Jordan).

Qadir told MEE his contacts with intelligence services were merely a routine part of his work with Home Office and counter-terrorism officials, and that he would have sought their advice about the case.

“We did have contacts with the security services and the intelligence services, but not to the point where I could call James Bond to go and pick him up,” Qadir said.

But Jervis recalls that ACF was involved in discussions about Jack getting out of Syria and the possible need for his parents to send him money. While Qadir was focused on Jack, Jervis’s main role was providing support and advice to his parents.

“In terms of law and protecting the family my role would be, well, if they are intending to send money I’d better give them some advice,” Jervis told MEE.

Some of this involved conducting risk assessments aimed at planning for different scenarios in which Jack was assumed to be either discontented, disillusioned or dangerous.

“Can he get out this way? Can he talk to that person? There was a whole lot of scenario planning,” said Jervis.

Jervis’s assessment was that they could only send money with the permission of the police and set about researching how this could be done.

'I found that there is a big misguidance in the state that I have nothing to do with'

Jack Letts' message about Islamic State

In early December 2015, Jack Letts sent a series of fateful messages to his mother.

It triggered a chain of events that was to lead to his parents' arrest just over one month later.

For the first time, Jack appeared open to leaving Syria and even returning to the UK. He asked Lane how long he could expect to spend in prison if he came home.

Most significantly as far as his parents were concerned, Jack said he wanted to leave because he said IS was teaching people “a huge creedal mistake”.

Jack said he had gone to Syria with the “intention of defending the Muslims who are being oppressed” and to “find more understanding of my religion”.

“I found that there is a big misguidance in the state that I have nothing to do with,” he wrote.

For John Letts and Sally Lane, the significance of these messages was clear: they understood that Jack was now in hiding and had set his mind on leaving. But they feared that even expressing these differences had increased the danger he faced from IS.

By this point, Lane and Letts were in regular contact with Qadir. Now they looked to him for guidance in organising Jack's escape.

In an email to Qadir on 11 December, John Letts wrote: “He's continuing to write to Sally regularly, and more frequently, about finding a way to get out, and he seems more desperate every time.”

Letts also mentioned that Rachel Mahon and Kerry Corbett, one of the SECTU investigators who had interviewed Lane in November, had visited them two days earlier.

Lane and Letts had discussed with the police whether they could meet Jack in Turkey if he was able to get himself across the border and out of Syria, and whether they could give him money once he was there.

'It seems mad that we all want him out, but they want him out so they can arrest him'

- John Letts

Letts told Qadir: “We’re in a position where we can’t really help him because we’d be supporting terrorism. It seems mad that we all want him out, but they want him out so they can arrest him, whereas we just want him to be safe.”

Mahon was “supportive” and considered it “great news” that ACF was involved in the case, Letts wrote. But, he said, he did not trust her colleague in the counter-terrorism unit.

“Should we be informing the police of all our actions and discussion?” Letts asked Qadir. “Would it make it worse if the police knew he was trying to get out?”

Writing back, Qadir appeared sympathetic about Letts' distrust of the police: “They have protocols in place and will only follow them because that is all they know what to do!”

It was obvious, he wrote, that Jack had “realised that ISIS follow a very warped ideology, nowhere close to Islam” and wanted to “free himself from them”.

Qadir added: “I am still hopeful of a good outcome and a solution, which I am working on with my ‘good friends’”, which Lane and Letts understood to be a reference to his contacts in the intelligence services.

In reply, Lane wrote to Qadir to request an urgent meeting: “We have been in touch with Jack and he seems to be making plans.”

A 'sticky situation'

Late in the day on 22 December 2015, Lane and Letts returned to ACF’s east London offices with the hope of finalising details of Jack’s escape plan.

“Basically, we thought this was our big chance,” Lane later told police, according to an interview transcript.

Part of the plan involved sending money in order for Jack to pay a smuggler to get him across a border. He would have to pay £1,000 upfront, and another £2,000 afterwards, he had told Lane.

Lane took notes during the ACF meeting. She says they were based on advice she received on buying a new SIM card and a cheap handset, with cash, to allow her to talk to Jack without her communications being intercepted.

“Active Change said they needed to know that the whole thing was genuine before they would agree to support him,” she explained to police in her interview.

“They wanted to know things like what his exit route was, how much it was going to cost, these were all the questions that we would need to ask Jack.

“And we would need a secure way of speaking to him, hence the SIM cards and what have you… and so that’s what we did. We came back and I asked Jack those questions.”

Meanwhile, Jervis was working on a strategy to protect Lane and Letts from potential prosecution.

“My view, based on what everybody had said, was that Jack needed money to get out of Dodge,” said Jervis.

“I said to John that we’ve got to assume that Jack is trying to get out for legitimate aims. Just make that assumption.

“If that’s the case then the request he is going to make is going to put you under pressure. Because if my son came to me and asked me to get him out of trouble, my parental instinct is to get him out of trouble.

“It was very important that we put some protective factors around them.”

But ACF was still talking to the police.

The next day, Qadir promised in an email to Rachel Mahon, the police Prevent officer, that he would update her “as and when we progress with Jack and his parents”. Qadir and Mahon were in contact again the following day, according to emails and phone records disclosed by ACF.

'Akhi, I write this with sincere intentions to assist you and your parents in such a difficult time, where they feel hopeless and pain whilst you are equally in a pretty sticky situation'

- ACF's Hanif Qadir writing to Jack Letts via Facebook

Neither Qadir nor police have said what was discussed, nor what Qadir was referring to when he promised to update Mahon. In his later statement to police, Qadir said his only contact with Mahon had been when she had been in touch at the beginning of November to discuss the case.

But plans for Jack’s flight seemed to be advancing.

On 24 December, for the first time, Qadir sent a message directly to Jack via his father’s Facebook account. Introducing him, John Letts urged his son to “have an open mind and give him a chance.

“He’s the first person we’ve met in the past two years who we think understands the situation and he’s offered to help us, and you, if you want it,” he wrote.

“I can’t really describe this offer in a message, but let’s just say that he has had a lot of direct experience of the world you’ve been living.”

Qadir then wrote to Jack:

“Akhi, I write this with sincere intentions to assist you and your parents in such a difficult time, where they feel hopeless and pain whilst you are equally in a pretty sticky situation.

"I can see from your message exchanges between you and your parents that you have realised the fact that the leadership/people around you are not upon the right manhaj [the path to truth], and are indeed applying a completely different creed of Islam.”

His final advice to Jack Letts was to urge him to trust in God, but also be careful.

“My main intention is to assist you in whatever way I can... Indeed it is the will of Allah that will prevail over any attempts by me or your parents to help you. However, let’s be mindful and ‘tie our camels’ so to speak.”

'We have been given clearance'

By 25 December 2015, it was clear that Jack Letts was becoming increasingly desperate. He had already told Lane that he wanted to flee Syria. He also shared the name of the person in Lebanon to whom his mother was to send the money to facilitate his escape.

“He told me, ‘They’re chasing me. I’m terrified. Please Mum, help me,'” Lane recalled.

Lane told her son she was still waiting for clearance from Qadir to send the money.

“The police need to be convinced that the money is for leaving otherwise I’m definitely doing two years. That is what Hanif can help with,” she wrote.

Jack replied: “I can’t just chill in the internet [cafe] all day every day waiting to have money for chips. Try and send it tomorrow morning ok?”

Two days later, Mahon put in a call to senior officers, telling them that Jack was urgently asking his parents for money to leave, and requesting advice to pass onto them.

'If they have an honest held belief Jack wants money to assist him leaving there is nothing we can do to stop them...'

- police senior duty officer guidance to Letts' parents

The lead investigators were off duty for the Christmas holidays but the senior duty officer offered the following guidance, according to extracts from police notebooks disclosed during the trial:

“If they have an honest held belief Jack wants money to assist him leaving there is nothing we can do to stop them... However they need to keep all correspondence with Jack to support their decision as this will be evidence in any subsequent investigation into their actions.”

Mahon’s notebook summary of this conversation read: “Money transfer an offence but not if purely JL return.” She was also tasked by the senior officer with the “evidential capture” of communications between Jack and his parents.

Mahon then called John Letts to pass on the news. In his later police interview, Letts recalled his reaction to that call.

“I was flabbergasterdly happy. I had this massive sense of relief. It’s like, ‘yes, we can do it but with the support of the police, this is fantastic,’” he said.

He told Lane, then rang Qadir. According to Letts, Qadir told him that the police’s green light to send the money was “fantastic news”.

But according to his later witness statement and courtroom testimony, Qadir had been surprised by the police advice.

“I can clearly recall winding my neck back into my shoulders thinking that was a bit strange,” he said in court. “I advised them [Lane and Letts] to check their position with the police.”

In his police witness statement, he said he had also phoned a contact in SO15, the Metropolitan Police’s counter-terrorism unit. Qadir told MEE that this referred to an ACF trustee who was a retired former senior Met officer.

“He is saying absolutely no chance. If the police have done that, that’s wrong,” Qadir recalled being told.

In his statement, Qadir also offered a different assessment of Jack’s motives for wishing to leave Syria, in sharp contrast with what he had suggested to his parents.

Now the ACF head was suggesting that Jack may have been planning to stage an attack in the UK or another European country.

“I considered Jack to be a threat to the UK should he return,” Qadir said.

At 3pm on 28 December, Jack reappeared briefly online.

'I considered Jack to be a threat to the UK should he return'

- Hanif Qadir's police witness statement

His mother told him: “We have been given clearance to go ahead. Do you still have a plan, and is that name still valid, or do you need to send another?” She added: “Please reply quickly.”

But Jack did not respond. The following day, on 29 December, the situation changed again with another call from the police.

This time the caller was Kerry Corbett. She told Lane that the advice they had been given by Mahon two days earlier had been overruled by the senior investigating officer. Corbett and Neath, the investigators who had interviewed Lane in September, would visit the next day to give them written guidance, she added.

The call sent Lane and Letts into a panic and left them with what they felt was an unconscionable dilemma. They had already told their son that the money transfer had been approved and feared that he had put his escape plan in motion.

The next day, Neath and Corbett visited Lane and Letts at home to deliver the written advice they had promised.

“The police do not endorse or authorise the sending of any monies to Jack Letts... However, the police cannot prevent such sending of money,” the guidance said.

“The police cannot confirm that any prosecution would necessarily follow; however, the parents of Jack Letts must be aware this is a possible outcome and therefore the decision whether or not to send the money rests with them, with no endorsement from the police.”

By then however, the couple had mostly made up their minds. The next morning, before her husband awoke, Lane left the house and tried to send £1,000 ($1,304) via a branch of Western Union to the contact details in Lebanon that Jack had provided.

And, although the police had told her that they could not prevent her sending money, the transaction was immediately blocked and flagged for investigation.

'We are where we are'

On 31 December 2015, the same day that Sally Lane tried and failed to send the money to her son in Syria, Mike Jervis had sent her an email which began, optimistically, with “Happy New Year!”

Jervis had been out of the loop with developments during the Christmas holiday. His email belatedly set out his advice to Lane and Letts on how they should set about seeking permission from the police for the transfer.

His advice was that they could seek to protect themselves by referring to the 2015 Counter-Terrorism and Security Act which created the so-called “Prevent Duty” – a statutory obligation imposed on public services to “prevent people from being drawn into terrorism”.

The police had so far failed to provide Lane and Letts with any evidence that their son was involved in terrorism. Jervis reasoned that by asking them to provide any such information under their Prevent Duty obligations, the couple could not then be accused of not having done all they could to avoid breaking the law.

He advised that Lane and Letts should ask police to apply their duty of care under the Prevent Duty by asking them for any information about their son that would help them to make an “objectively informed decision”.

But in Oxford, Lane and Letts were making preparations for their anticipated arrest.

As part of this, Lane sent Jervis documents relating to the case and asked him to keep them safe as they expected their computers and phones to be seized.

Jervis wrote back with words of support, telling the couple: “I cannot logically see how extracting your son from a conflict zone after informing the police will constitute terrorism”.

“Your help is... heaven sent, my friend. Thank you,” John Letts replied.

On 4 January 2016, Lane again tried to send money, this time £500 ($652). Again it was blocked.

Early the following morning, Sally Lane and John Letts were arrested by police and taken into custody to be interviewed.

Corbett asked Lane whether she had understood that she could be arrested for sending money to Jack, based on the information sheet she had been given a few days earlier. Lane replied that she had decided she was prepared to face the consequences.

“I think I need to get him out alive and I think every day we're sitting here, he could be, you know, he could be killed right now,” Lane said. “I feel I should actually be out there communicating with him and not sitting here.”

Lane complained that the police had told them they could send the money, and that she had told her son that permission had been approved.

'I think he's in great danger and I can hardly sleep as a result of it'

- John Letts

Corbett replied: “I am aware that you were given misleading advice, and obviously as soon as I was aware I made you aware that it was wrong. We are where we are, aren't we?”

The transcript of Letts’ interview by Neath on the same day also gives a sense of his growing impatience with the police.

Letts complained: “I think he's in great danger and I can hardly sleep as a result of it. I had another nightmare about him last night and it's just horrible to think that he's not going to make it and I am being blocked at trying to protect him.”

Neath asked Letts what checks he and Lane had made to ensure that that the money would be used by Jack to fund his escape.

“Well, what checks could I have possibly done?” Letts replied. “I have no intelligence operatives working inside Syria or Lebanon.”

Asked if Jack had told them explicitly that he was in extreme danger, Letts laughed dismissively.

“Sorry, he's in Syria,” he said. “They're killing people for contacting people in the West, for being spies. It's a sinking ship where the rats are starting to eat each other.”

'That was when the penny dropped'

It was during a subsequent round of interviews on 23 February 2016 that Letts says he finally realised that the trust that he and his wife had placed in Qadir had been misplaced.

“I was stunned. I couldn’t believe it. That was when the penny dropped,” Letts told MEE.

“I was going on about Hanif. I kept saying to the police, ‘Come on guys, make a phone call, Hanif’s on this case’. He kept going on about these intelligence contacts. He said they were going to give us high-level cover.”

But by then, Qadir had provided police with his statement in which he suggested that Jack was a potential threat to the UK.

The police put this information to Letts during his interview. Later he wrote to Qadir: “As it stands, I feel deeply let down and confused given all that you said to us.”

In the weeks after their arrest, Lane and Letts had continued to lean on ACF for support.

Most significantly, they agreed at Jervis's suggestion, that it would be a good idea to be interviewed by a journalist who would write about their case to test public interest.

Jervis said that this might also work in their favour if they ended up being prosecuted. He proposed that they would remain anonymous and that details would remain sufficiently vague so that neither they nor their son would be identifiable.

“We agreed on the basis that we were worried about identifying Jack and putting him in danger,” said Lane.

Jervis put them in touch with Richard Kerbaj, a Sunday Times journalist who had also produced “My Son the Jihadi”. But the story did not go to plan.

The couple met with Kerbaj in Oxford early in January 2016 and he later, they said, read them extracts from his draft copy over the phone. They were concerned that it contained too much identifying information and asked Jervis to intervene to stop it being published.

According to Jervis, the original plan had been that he would be present for the interview, in order that the couple would not say anything that they were not happy to see in print.

Jervis recalled: “I’m saying to John, be careful because a journalist is a journalist. And then it goes pear-shaped. If you had stuck to the agreement, I would not have had to cool this down.”

Letts disputes this account. He said that Jervis had encouraged them to meet the journalist: “[Kerbaj] phoned and then he showed up. But Jervis was always supportive.”

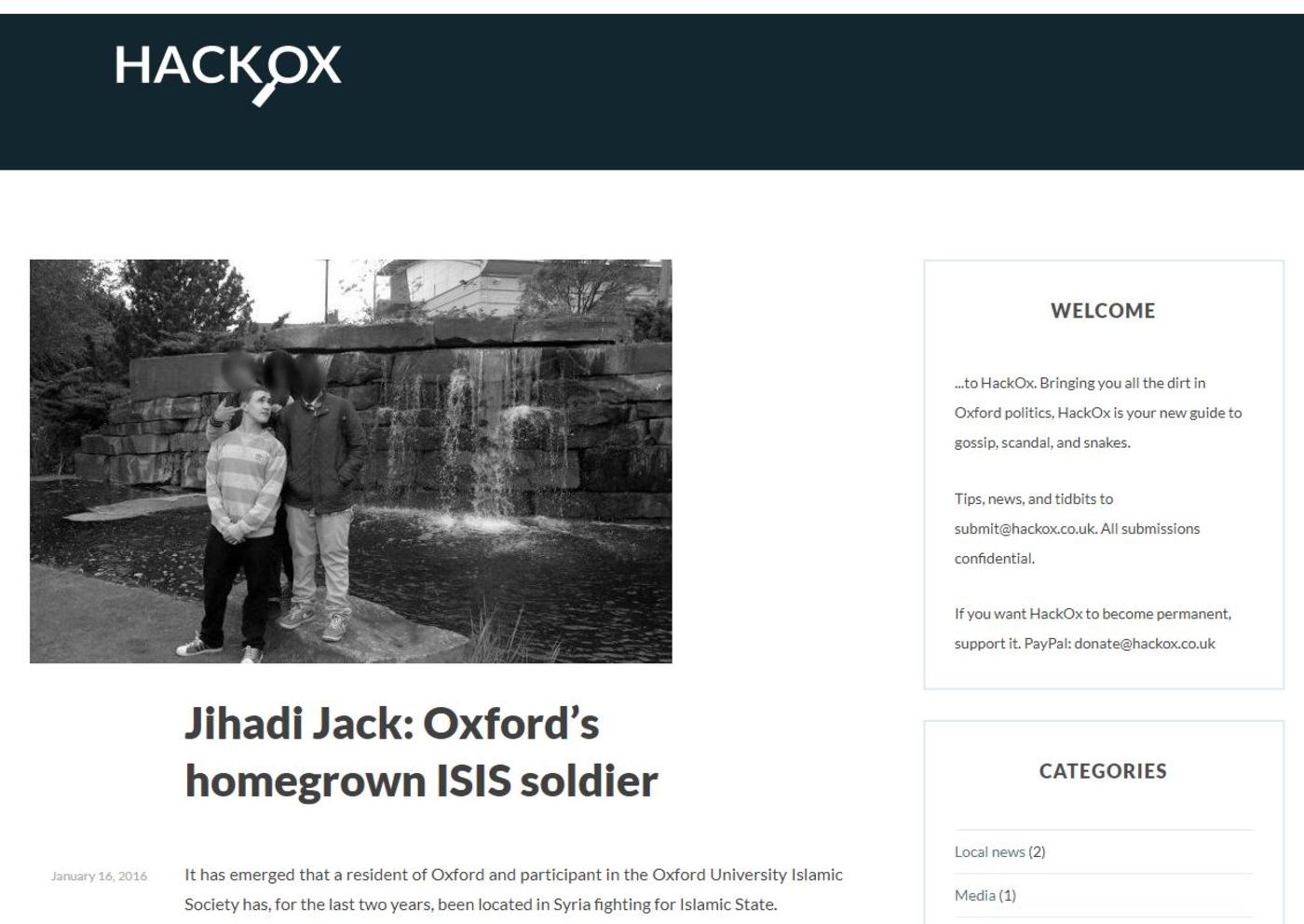

But then, on 16 January, a story about Jack Letts appeared on an obscure website called HackOx which was mostly focused on Oxford University student politics. Neither Letts or Jervis know how the website got the story and the Sunday Times is clear that neither they nor Kerbaj leaked the story.

MEE could not contact HackOx because the website no longer exists. A Twitter account for the site was set up in January 2016 but has been inactive since March 2016. The earliest archived pages date from January 2016, while the last story published on the site appears to date from 23 February 2016.

“Jihadi Jack: Oxford's homegrown ISIS soldier,” the headline said. The story alleged that Jack had been fighting for IS in Syria and “had already been made known to MI5 by his father”.

Jervis was still wrangling with Kerbaj but the story was now in the public domain. On 24 January, the Sunday Times ran its story under the headline “'Jihadi Jack' first white British boy to join ISIS”.

“We were horrified because the story was only about Jack. It called him 'Jihadi Jack'. It said he admitted joining ISIS. It went all over the world at lightning speed. We just couldn't control it,” said Lane.

'We were horrified because the story was only about Jack. It called him 'Jihadi Jack'. It said he admitted joining ISIS'

- Sally Lane, Jack's mother

Lane said the couple had not told anyone that Jack had admitted joining IS because he had not made any such admission to them.

She believes that the story created a situation in which their prosecution became more likely, and could not be quietly dropped, because of heightened public awareness of the case.

MEE put Lane’s allegations to the Sunday Times. A spokesperson for the newspaper said: “We stand by our journalism and the accuracy of our reporting on this story."

Jervis concedes that his plan to create a mood of public sympathy around the case backfired.

But he says it was the headline that did the real damage by associating Jack Letts with Mohammed Emwazi, the leader of a British cell of IS executioners who had been nicknamed “Jihadi John” by the media.

“It created Jihadi Jack which associated him to Jihadi John. In that sense the damage was done.”

A 'proper punchup'

By February 2016, the focus of the police investigation into Lane and Letts had shifted to ACF itself - the organisation whose work with the couple the police had themselves facilitated.

Over the next few weeks, Qadir and Jervis met investigators several times both at SECTU’s headquarters in Slough just west of London and at ACF's offices.

Both Qadir and Jervis initially agreed to be interviewed by police, and indicated that they could also provide statements about their work after first checking with the Home Office.

In early March, Neath visited ACF's office with a financial investigator to formally inspect the organisation's bank accounts. Police said this was to check whether it had provided the funds which Lane had tried to send to Jack. The visit went well, according to Neath's follow-up email.

“Many thanks for your and Hanif's assistance on Thursday,” Neath wrote to Jervis. “It was a genuine pleasure to visit the foundation and see some of the good work you guys do.”

Jervis used the meeting to urge the police not to press charges against Jack’s parents. Instead, he suggested, the case offered an opportunity to demonstrate that the Prevent strategy was working in a “just and transparent way”.

‘You lot have done wrong. I don’t believe they should have been arrested, let alone charged or prosecuted’

- Mike Jervis, ACF head of strategy and research

“We can use this to silence the Prevent detractors,” he wrote to Neath. “I really think we can do something to increase the confidence in the agenda if the decision not to charge is properly managed.”

But below the surface there appear to have been sharpening disagreements between ACF and the police about the organisation’s entanglement in the investigation.

“Don’t worry about how the paperwork looks, behind the scenes there was a proper punch up,” Jervis told MEE.

Jervis said ACF’s trustees had told them to seek legal advice on whether to hand over information to the police. The advice was that they should not. Instead, Jervis, said, the organisation told the police that they would provide its files to the Letts family.

“From my point of view, I was open and transparent all along. I said I’m not having a part of this,” said Jervis. “I said, ‘You lot have done wrong. I don’t believe they should have been arrested, let alone charged or prosecuted.’”

A particular flashpoint occurred after John Letts’s angry email to Hanif Qadir in late February 2016 after police had told Letts that Qadir said that Jack was a security threat.

“The police tells us not to say anything and then breaches that confidence. Nice one,” Jervis wrote to his colleague. “I don’t like being set up.”

The pressure brought to bear on their organisation was also affecting the once-close relationship between Qadir and Jervis.

Jervis says he only found out later that Qadir intended to testify against Jack’s parents after reaching out himself to the couple’s solicitors to offer his help with their side of the case.

After learning about the allegations that Qadir had made against the couple in his statement, Jervis said he had confronted his long-time friend and colleague.

“We were like brothers so I was upset,” Jervis recalled.

“I said, ‘Okay, that is slightly wrong son because at the end of the day they are our case. If you are giving advice then you go down with your case."

Jervis instead offered himself as a witness for the defence, writing a statement in which he questioned Qadir’s judgement.

“By being a witness for the prosecution, we are undermining our own client's case. My view is that this is unethical and should not be done by an ACF officer without good reason,” he wrote.

'If you are doing counter-extremism you don’t put Office for Security and Counter-Terrorism above the door because no one is going to come'

- Hanif Qadir, ACF

Jervis told MEE he was unaware of the police plan to gather intelligence on the Letts family through ACF.

But Qadir concedes that ACF’s role had been operating in a “grey area” because of the sensitive nature of its work.

He said: “If you are doing counter-extremism and deradicalisation you don’t put Office for Security and Counter-Terrorism above the door because no one is going to come.”

Qadir said he had told Lane and Letts from the start that he would pass on information to the authorities if he had concerns that public safety was at risk.

But Jack’s parents dispute that they were told this. Letts did sign a consent form on the couple’s behalf, allowing Qadir to “liaise and negotiate with legal authorities and any other necessary agencies related to help me and my family” – but the couple say they understood that this granted Qadir permission to approach his contacts to seek their help in getting Jack out of Syria.

“He told us all our conversations were confidential, and he advised us on hiding our communications,” said Lane.

There is one thing on which Qadir and Jervis still agree, however. They believe ACF’s involvement in the Jack Letts case was why the organisation lost its Home Office funding later in 2016. This, they say, eventually led to ACF closing in 2018.

”When the Letts got arrested we were called up to the Home Office and they told us in quite distinctive terms their displeasure at the case,” said Jervis.

Qadir adds: “I was told the home secretary [then Theresa May] was afraid of the media attention the case would bring,” he said.

“What I look at is getting my hands dirty, working with individuals of concern and turning them around. I said if you don't want us to do that then you are funding the wrong organisation.”

According to Jervis, the Home Office had initially allowed ACF to operate without interference.

“We were the number one. We were getting all the hardcore cases. People were walking in our door and saying ‘My brother is in Syria'.

“We told the Home Office, ‘You are not getting any information out of us because that is not what the job is'. And they told us back, ‘So long as you run your projects how you are supposed to run your projects then we are good.’”

But, Jervis notes, over time, the Home Office became more intrusive, keeping a closer eye on ACF’s activities and how its Prevent money was being spent.

The Home Office’s focus, he added, was shifting to online influence campaigns, such as ACFs #NotInMyName, at the expense of on-the-ground counter-extremism work.

'The Home Office put a media team around us. Any media enquiries would go to them first'

- Hanif Qadir, ACF

Qadir also expresses frustration at the direction in which ACF had been pushed.

“The Home Office put a media team around us. Any media enquiries would go to them first. They would say, speak to so and so and by the way go along these lines. It was almost like speaking for the government.”

A spokesperson for the Home Office told MEE: “We expect those who receive public funding to act with the standards of professionalism and we reserve the right to halt support to those who do not do so.

“The Home Office took a number of reasonable and proportionate steps to ensure that concerns were being properly addressed with the Active Change Foundation, including a verbal warning and suspension as a Channel Intervention Provider, before the decision was eventually taken to end our relationship with ACF.”

Responding to the Home Office's statement, Qadir said ACF had been showcased around the world by the Office for Security and Counter-Terrorism as an example of best practice.

"We were tasked to train other organisations to be recipients of funding," he said.

"All of a sudden in May 2016 we became unprofessional? That is utter nonsense."

'For the love of their child'

John Letts and Sally Lane appeared at Westminster Magistrates Court on 9 June 2016, charged on three counts of entering into a funding arrangement for the purposes of terrorism, relating to the £233 sent to Lebanon in September 2015 and the failed attempts to send money on 31 December 2015 and 4 January 2016.

They were initially remanded in custody on the basis that they might try to send money to their son again, despite having been at liberty to try to do so since their arrest in January.

The ruling was overturned six days later and they were freed on bail. “Two perfectly decent people have ended up in custody because of the love of their child,” said Mr Justice Saunders, the judge who ordered their release.

A series of preliminary legal skirmishes then delayed their main case. First they went to the Supreme Court to seek clarity about the wording of the offence, which required the accused to have “reasonable cause to suspect” that the money might be used for terrorism.

Lawyers for Lane and Letts argued that the charge ought to require “an element of a guilty mind”. The Supreme Court disagreed. It was sufficient, it ruled, for someone to commit the offence if, based on the information they had, they should have suspected that the money might be diverted into terrorism.

But, in a victory for the couple, the Court of Appeal rejected the prosecution argument that the couple should be denied the common law defence of duress.

This allowed their lawyers to argue, though only for the latter two charges relating to the failed attempts to send money, that they had acted because they believed that Jack’s life was in danger.

On 22 May 2019, the trial of John Letts and Sally Lane began at London's Old Bailey.

Among those who took the stand against them were Hanif Qadir and Rachel Mahon, the Prevent officer once described as “sympathetic” by John Letts.

“We felt utterly betrayed,” said Lane.

Defending Lane and Letts, their barrister Henry Blaxland described the trial as “inhumane to the point of being cruel”.

'This prosecution does absolutely nothing to further the prevention of terrorism'

- Henry Blaxland, barrister

“This prosecution does absolutely nothing to further the prevention of terrorism,” he said. “In fact it runs the risk of undermining the fight against terrorism because it runs the risk of bringing the law into disrepute. Law without compassion is not justice.”

Less than one month later, the jury found Lane and Letts not guilty on the 31 December 2015 charge. It also failed to reach a verdict over the 4 January 2016 charge.

But the couple were found guilty over the £233 sent to Lebanon at Jack’s behest in September 2015 - a charge they only faced because they had also been prosecuted over the later attempted payments, for which they faced no sanction.

Prosecutors never argued that the couple had funded or ever intended to fund terrorism. Instead their case rested on the fact that there were “reasonable grounds” for them to suspect that the money could potentially have been misused.

Sentencing them to a suspended 15-month prison term, Judge Nicholas Hilliard agreed. “The warning signs were there for you to see,” he said.

'We are on our own'

Sally Lane and John Letts have not heard from their son since receiving a letter delivered via the International Red Cross (IRC) in August 2019.

Jack Letts is currently among hundreds of other suspected IS members being held in a Kurdish-run prison in northeastern Syria.

His parents had been able to keep in touch with him sporadically for a while after the money transfers were blocked but by then he appears to have been spending most of his time in hiding. He was eventually picked up by Kurdish forces in mid-2017, some time after telling his parents that he had finally left IS territory.

In September 2019, Crispin Blunt, a British member of Parliament was able to visit Jack in prison. Blunt had originally been appointed as an expert witness by lawyers for Lane and Letts, as well as being tasked with attempting to negotiate Jack Letts' release with the Kurdish authorities in order that he could return to the UK to stand as a witness in their defence at the trial.

Blunt was able to deliver Jack letters from his parents, reporting back that he was “fit and well if not exactly full of the joys of spring”.

In October, the IRC told the couple that it had halted its visits to the prison because of security concerns following Turkey’s attack on Kurdish forces.

“We have had no proof of life since October,” said Letts. “We are waiting for either bad news or a Red Cross letter.”

Neither the UK nor Canada has so far shown much appetite for the repatriation of nationals accused of links to IS. Like many other British dual nationals in Syria, Jack has also been stripped of his citizenship, a move which prompted the Canadian government to complain about the UK “offloading its responsibilities”.

Lane and Letts now hope to go to Canada to raise awareness about Jack’s case, but even travelling to a country where they both hold citizenship is no longer straightforward.

They have been advised that their terrorism convictions mean they will likely be prevented from boarding a plane to Canada on the basis of a US no-fly ban which affects flights from the UK to major Canadian airports. Instead Lane is now making plans to cross the Atlantic by ship.

Legal fees have cost the couple their home and their family finances. Their bank accounts were shut down as a consequence of the investigation. They have survived through the support of friends, who have sometimes themselves attracted the attention of the police.

Shortly after a dairy farming friend offered to pay Lane and Letts’ rent, he received a visit from police officers who warned him that he could also face investigation for funding terrorism if he passed on money to the couple.

The friend suggested to the officers that perhaps he could instead donate them some of the cheese produced on the farm. No, the police warned him, that was not allowed either. Sally Lane and John Letts could sell the cheese to fund their suspected terrorism-related activities.

The Prevent programme continues to haunt Jack Letts’ parents in unexpected ways.

John Letts says the couple has been unable to access confidential mental health care because psychiatrists they have approached have warned them that they could be required to pass on details to the authorities under the Prevent Duty.

“We are in one of the most stressful situations anybody can go through and we cannot get confidential psychological support,” he said.

“We are on our own, just the two of us, and there is so much stress.”

Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust told MEE that it could not comment on individual cases.

A spokesperson said: “We have a responsibility to fulfil our safeguarding obligations to protect people who may be vulnerable to exploitation.

“In some cases that could involve seeking advice from the police under the Prevent Duty and we are obliged to advise people of this possibility.”

Tayab Ali, their lawyer, says that Letts and Lane have good reason to feel that they had been set up and misled by the way that their case was handled by the police and by ACF.

'We are in one of the most stressful situations anybody can go through and we cannot get confidential psychological support'

- John Letts

Of the police investigation into them, Ali said: “They suggested to them that they were prepared to help when in fact they were just evidence gathering.”

He points out that ACF could have simply advised them to seek permission to send money to Jack through section 21 of the 2000 Terrorism Act, which states that a person cannot commit a financing terrorism offence if they are acting “with the express consent of a constable”.

Section 21 could also have been used by the police to bring absolute clarity to the situation. The legislation states that an offence is committed if someone goes ahead with a transaction when a constable has forbidden them from doing so.

“Sally and John would have had no defence if they had been forbidden from sending money,” said Ali.

MEE put a long list of questions to Counter Terrorism Policing South East (CTPSE) regarding SECTU’s handling of the investigations into Jack Letts and his parents and the issues raised in this article.

CTPSE did not answer MEE’s questions and instead sent a statement in which it said:

"Following a three week trial at the Central Criminal Court in London in June 2018, John Letts and Sally Lane, were convicted of one count of sending money which they had a reasonable suspicion could be used for the purposes of terrorism, contrary to Section 17 of the Terrorism Act 2000.

"Counter Terrorism Policing South East (CTPSE) has always maintained that we do not consider John Letts and Sally Lane to be terrorists and there is no suggestion that they supported the ideology or actions of Daesh in any way. However, they consciously chose to send money to their son despite knowing or suspecting that it might be used by him to support terrorist activity or it may fall into the hands of others who may use it for that purpose.

'The law around this is clear and applies equally to everyone, regardless of their motives and it is here to help stop the funding of terrorist organisations and individuals'

- Counter Terrorism Policing South East (CTPSE)

"The law around this is clear and applies equally to everyone, regardless of their motives and it is here to help stop the funding of terrorist organisations and individuals. Despite warnings from detectives, Mr Letts and Ms Lane ignored the advice and continued with their plan. By doing so, they broke the law and were found guilty by a jury of their peers.

"CTPSE will continue to work to keep the public safe and to mitigate the threats posed by terrorism, including stopping funds getting into the hands of terrorist organisations in the UK and overseas. We carry out our investigations to gather the evidence to enable the Crown Prosecution Service to make decisions on whether to prosecute those who ignore the law.

"It would not be appropriate for CTPSE to comment on any active ongoing investigations; however, the threat posed by UK nationals seeking to return from Syria or Iraq is something that we and our colleagues across the Counter Terrorism Policing network have planned for and have been managing. Together with our intelligence partners we have been using a wide range of measures and powers available to us to mitigate this threat.

"Anyone who returns from Syria or other conflict zones, having gone in support of any proscribed terrorist group – whether that’s fighting for or against Daesh – or for any other illegal purposes, can expect to be investigated by the police.

"Any investigation is carried out with an open mind and based on the evidence available. This is to determine if individuals have committed any terrorist or other criminal offences, regardless of their motivation, and to ensure that they do not pose a danger to the public or the UK’s national security.

"As a society we need to do all we can to prevent terrorist activity from happening in the first place, reporting any concerns in order that we can intervene early enough before people move into the space where prosecution becomes necessary."

The Home Office spokesperson told MEE that Prevent was working and was making a significant impact in preventing people being drawn into terrorism.

The spokesperson said there was nothing in law, or in guidance or training, that requires, authorises or encourages any form of spying in connection with the Prevent Duty.

Yet many of those involved in the Jack Letts case believe that it demonstrates a failure of policy-making in government over the issue of British citizens returning from Syria, to where hundreds travelled from the UK, and a refusal to recognise any distinction between their motivations and activities.

Those critical of this policy include Hanif Qadir who said that the government had created a “hostile environment” which disregarded the human rights of those who had gone to Syria, regardless of their individual circumstances.

By subsequently turning a blind eye to the fate of those now stranded, Qadir said the government risked “confirming a narrative that if you are a Muslim you are going to be disregarded and your human rights amount to nothing”.

'In this case many felt as though Sally and John were being made an example of because they were white middle-class non-Muslim parents'

- Tayyab Ali, lawyer

Lawyer Tayyab Ali suggests that the Lane and Letts case posed a particular problem for the government and prosecutors because the accused did not fit the template of the usual suspects – namely, brown-skinned Muslims – typically caught up with little public sympathy in the dragnet of draconian terrorism laws.

He compares their case to that of Salim Wakil, convicted earlier in 2019 with rather less publicity for sending money to his sister in Syria, which he also said was intended to help her return to the UK.

In sentencing Wakil, the judge noted that he suffered from “serious mental health problems” and was “suggestible and vulnerable”, and acknowledged that he had been manipulated by his sister. Nonetheless, Wakil was jailed for 30 months.

While Sally Lane and John Letts escaped with a suspended sentence of less than half that length, Ali suggests cases such as Wakil’s created a need for prosecutors to be seen to be applying the law consistently, with the result that Lane and Letts were "ferociously prosecuted".

“In this case many felt as though Sally and John were being made an example of because they were white middle-class non-Muslim parents. It felt as though there was pressure to prove that it is not just Asian people who are subject to these laws," he said.

"Allowing this to be one of the reasons to prosecute is still a form of prejudice that my clients had to unfairly deal with. Sally and John always wanted to do the right thing. The bottom line is the state let them down.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.