Lebanon's electricity crisis plunges Beirut, country into darkness

Wandering the streets of Beirut after sunset, car headlights are often the only thing breaking through the pitch-black night. The omnipresent sound of car engines during rush hour fades away at night, to be replaced by the buzz of generator engines, as if Beirut were a giant beehive. But instead of honey, the air of the city is thick with the smell of generator exhaust fumes.

Like the rest of Lebanon, the country's capital has been struck by acute fuel shortages, which have meant residents have had little, if any, state-supplied power for the past few months.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Lebanon's state electricity company, Electricite du Liban (EDL), warned in September that the country could plunge into a total blackout in October, amid dwindling fuel reserves, as the company is unable to generate the minimum 600 megawatts needed daily for the network to function properly.

On Saturday, EDL once again raised the alarm as the electrical grid shut down across the country - meaning residents of Lebanon are now entirely dependent on costly private generators for power, if they can even afford it.

The electric grid shutdown comes amid an already devastating economic crisis blamed largely on decades of corruption and mismanagement by the ruling class, with the Lebanese currency losing over 90 percent of its value in less than two years.

A new government was sworn in on 20 September, after more than a year of political paralysis, a development described by Prime Minister Najib Mikati as lighting “a candle in this hopeless darkness” - an ironic metaphor, given that the swearing-in process was delayed for several hours due to a power cut in parliament.

The dark nights, however, obscure the ways in which the absence of electricity transform daily life once the sun rises - and things are getting worse. Basic food items have now become a luxury, and what were once anecdotal details of life during the civil war have become a reality once again for many - with no end in sight.

‘Too risky to sell dairy products’

Until recently, Mohammad Kichly opened his barber shop in the neighbourhood of Qasqas at sunrise - not because he is a naturally early riser, but because he wanted to take advantage of the single hour of electricity provided by EDL to charge his equipment.

“I used to get a good night's sleep and open the barber shop around 9am, and customers don’t usually show up before 11am,” he tells Middle East Eye. “After all, I don't own a bakery.”

“August and September were hell,” he adds. The summer heat had forced him to move his barber chairs onto the pavement outside his shop. “The customers couldn’t bear the heat with no air-conditioning. I had already started to lose my customers with the economic crisis and skyrocketing prices for private generators… the electricity cuts were a death sentence for me.”

With the arrival of October, temperatures have dropped, allowing Kichly to bring his customers back inside. However, as winter approaches, many Lebanese fear the drop in temperatures will bring its own challenges.

Adham al-Rifai, a resident of the city of Baalbek, 1,170 metres above sea level, says he was lucky enough to stock up on diesel for the winter before subsidies were removed - but friends and relatives were not so lucky.

“To survive the winter season, one needs around 10 times the minimum wage each month in order to buy the necessary diesel,” he explains to MEE.

Before the electricity crisis, each year brought stories of Syrian refugees freezing to death in Lebanon’s mountainous areas. Now, Rifai warns, “we should expect news of mounting death tolls from the cold, not just among Syrians but also among Lebanese”.

Across the street from Kichly’s barber shop, Rami Hussein owns a small grocery store - but in recent months he has had to severely pare down the items available for sale.

“I no longer sell any dairy products, it is too risky now,” he tells MEE. “Imagine if any of my customers, who are also my neighbours, get food poisoning because they ate spoiled cheese bought from my store.”

Being a small neighbourhood shop owner, Hussein prioritises his reputation above all, but he feels stuck between a rock and a hard place.

“If I want to keep my refrigerators running on a private generator, I will have to pay more than I earn,” he explains. “It's not worth it. But with cutting back on some products, I no longer generate the necessary profits to make ends meet for my family.

“The light at the end of the tunnel that people talk about seems to be out as well.”

On the usually bustling Makdessi Street, Ghassan Houry still welcomes customers to Hamra Vintage store, as long as they can use the flashlights on their mobile phones to browse through items during electricity outages. Houry takes pride in the wares sold in his shop, but is heavily dependent on an expensive private generator to show potential clients that his chandeliers and vintage electric appliances on display do work.

"I live in Badaro and drive to Hamra, and I struggle to secure fuel to get to work. I get here and there's no electricity. It's one thing on top of another," he tells MEE. "Customers are not staying long because of the lack of light, and my products are not getting seen. Add that to the economic situation and people not having money..."

Elsewhere in the Hamra neighbourhood, Ahmed Takoush and his wife, Samar Itani, rely on a small, rechargeable battery-operated light in their La Polina flower shop during blackouts. The couple have to be strategic about using air-conditioning in order to preserve the cut flowers on sale - even if it means turning off every other appliance.

"At least I don't run a dairy business," Takoush says, the exhaustion audible in his voice.

Reliving the war

While the electricity crisis has made it hard for people in Beirut to earn a living, home life has not been spared either.

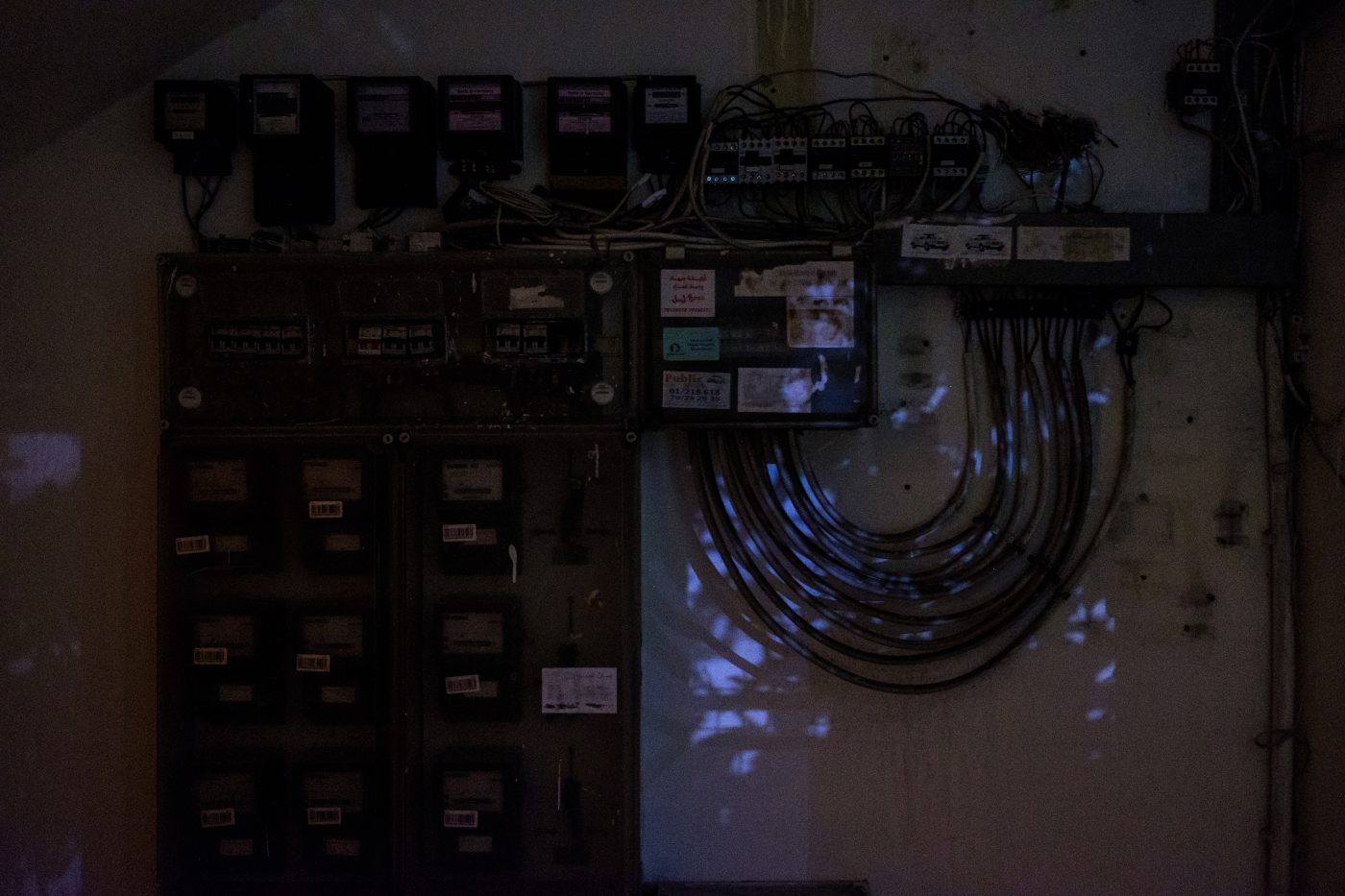

In Furn el-Chebbak, the numbers on apartment buildings’ electric meter boxes stand frozen in the absence of any EDL-supplied electricity.

"We work to pay the generator providers and still we get power cuts," the owner of a minimarket in the area tells MEE. The man asks that his name not be mentioned, out of fear, he says, that his generator provider might cut him off completely if he complains.

'We live in peacetime now, but the ruling political class is waging a war against us and our children'

– Layane, a mother of two

Most Beirutis rely on private generators, also known as ishtirak - but even private providers have had to impose their own power cuts for at least six hours a day, due to fuel shortages. Those who can afford it have purchased uninterruptible power supply (UPS) backup units, batteries and a voltage regulator when both state and private electricity are not available.

Suzanne Charafeddine is a 60-year-old laboratory technician in one of Beirut’s private hospitals. A resident of the southern suburbs, she is due to retire in four years, but her pension has been almost completely wiped out with the freefall of the Lebanese pound.

As frightening as it is to be deprived of a safety net, this is not what worries her every day.

“My biggest daily concern is how to climb the stairs to reach my apartment on the seventh floor after a long, tiring day,” she tells MEE. With the government phasing out subsidies on fuel, electricity has become so expensive that she has had to lower the amperage to avoid spending her entire salary on the generator bill alone.

“My neighbours did the same, and to cut back on expenditures the building committee decided to cut off electricity from the elevator,” she explains. “I guess wanting a good view in Lebanon turned out to have a big price at my age.”

Over a year and a half since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, Lebanon’s schools finally reopened in September - but the return of in-person classes has done little to bring back a sense of normality for families.

Layane would tell her two children stories of how she studied by candlelight during Lebanon's 15-year civil war, which ended in 1990.

“I never thought that my kids would relive what my generation went through,” the mum, who requested that only her first name be used, tells MEE, with the anger clear in her voice. “We lived in this misery then, but there was a war: getting through the day and living to see the next made everything else seem normal.

“We live in peacetime now, but the ruling political class is waging a war against us and our children.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.