Saudi import ban spells more trouble for Lebanon's economy

Saudi Arabia’s recent decision to ban imports from Lebanon is the latest crushing blow to Beirut’s already battered economy, set to lose out on $250m in revenues if ties are not mended over a diplomatic spat that broke out last week.

The move is in retaliation against Lebanese Information Minister George Kordahi’s remarks calling the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen “absurd”, which Riyadh described as “insulting”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

The kingdom’s decision to punish Lebanon both diplomatically and financially marks the fourth hit to the Lebanese economy in the past two years, already reeling from a financial crisis that has led the Lebanese lira to depreciate by more than 90 percent, the Beirut port blast that devastated the capital in August 2020, and the Covid-19 pandemic.

If other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries follow Riyadh’s lead - Bahrain, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates have already recalled their ambassadors and taken other punitive steps - Lebanon could lose over $1bn a year at a time when it cannot afford another setback.

Exports on the line

“The country is in a situation where it needs every dollar that comes in, to make an effort to maintain whatever it has and not regress,” Laury Haytanian, a Beirut-based energy expert, told Middle East Eye.

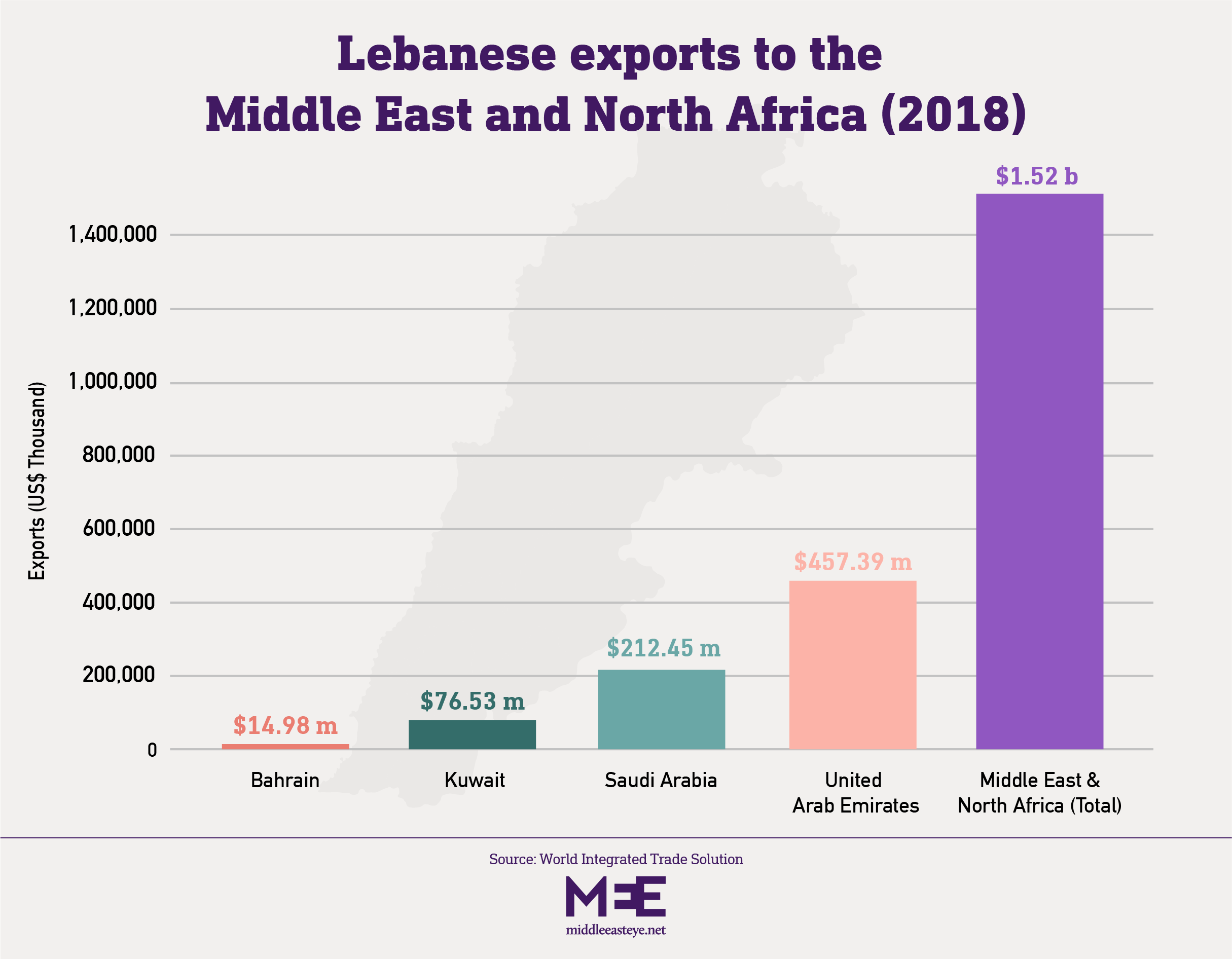

According to the latest available figures, Saudi Arabia accounted for 6.92 percent of Lebanon’s exports in 2019, worth $282m according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), with goods ranging from jewellery, chocolate, processed foods, fruits and vegetables.

If the UAE, which has shuttered its Beirut embassy and put the land up for sale, and Kuwait follow Riyadh’s lead, the impact on the Lebanese economy will be even harder. The UAE accounted for 15.2 percent of Lebanon’s exports, worth $619m, and Kuwait 5.74 percent, worth $234m in 2019, according to the OEDC.

In contrast, Lebanon accounts for just 0.16 percent of Saudi Arabia’s exports worth $263m, of which a quarter are petrochemicals, and nearly 9 percent of Lebanon's milk and cheese imports.

Combined with Saudi Arabia, around $1.13bn in annual revenues are on the line.

Saudi Arabia is a major export market for Lebanese food and agriculture producers, with some 100,000 tonnes of fruits and vegetables sold to the kingdom every year worth $24m, according to the Bekaa Farmers Association.

In April, Riyadh temporarily banned the import of Lebanese fruit and vegetables after 5.3 million Captagon amphetamine pills were discovered hidden in boxes of pomegranates at Jeddah port.

Lebanon will not be able to readily shift such exports to new markets due to its agricultural produce not meeting European Union (EU) standards, as well as not being price competitive with other markets.

'The Gulf is the only export market. There’s no capacity to pivot to the EU, Asia or North Africa'

- Sami Halabi, Triangle Consulting in Beirut

“The Gulf is the only export market. There’s no capacity to pivot to the EU, Asia or North Africa,” Sami Halabi, director of knowledge and co-founder of Triangle Consulting in Beirut, said.

The unregulated use of pesticides on Lebanese produce has also caused multiple bans by Gulf countries in the past. Just last week, Qatar banned the import of Lebanese herbs after finding high levels of pesticides and E.coli.

The Saudi import ban could also mean a potential loss for Lebanese information and communications technology services, streaming and e-commerce platforms.

“There’s a lot of Arabic language content coming out of Lebanon geared at the Gulf market,” Halabi said. “If they ban Lebanese IP (internet protocol) addresses, the Lebanese will have to play cat and mouse to get around this.

"People [in the Gulf] won’t want to have to use a virtual proxy network to access Lebanese platforms, they want to plug-and-play, so will use other service providers instead.”

Facing an economic abyss

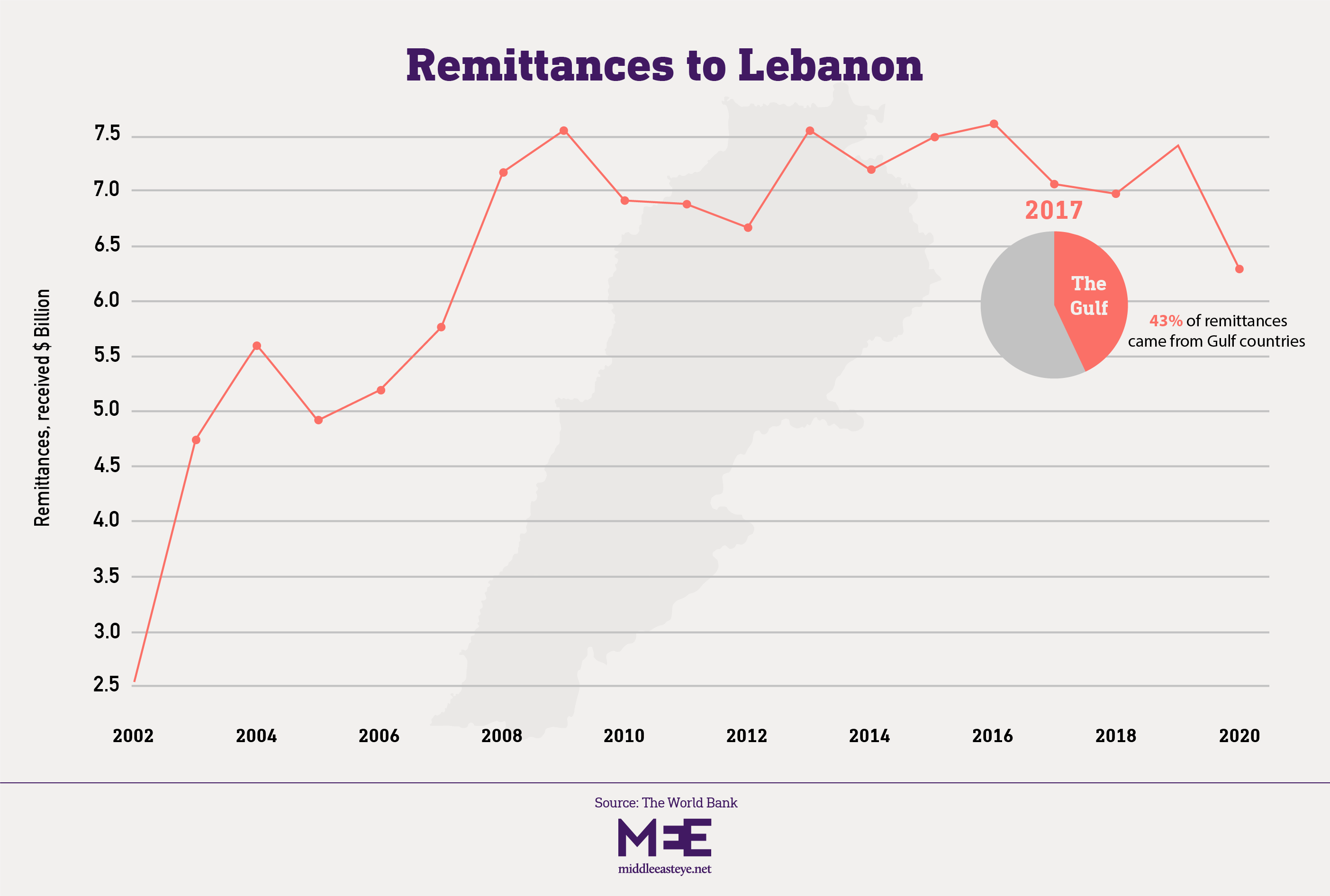

Riyadh’s calls for Kordahi to resign and its willingness to increase pressure on the small Mediterranean country have led to growing anxiety that the kingdom could escalate to banning financial remittances being sent from the kingdom to Lebanon.

“That would be a great blow as Lebanese are relying on remittances now more than ever,” said Haytanian.

There are an estimated 350,000 to 400,000 Lebanese citizens living in the GCC region, the majority of them in Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Remittances from the diaspora have long been an essential part of the Lebanese economy, amounting to $7.3bn in 2017, or 12.5 percent of Lebanon’s GDP. The Gulf accounted for 43 percent of remittances into Lebanon that year.

What is being termed a “blockade” of Lebanon by Riyadh has drawn parallels to the 2017-2021 blockade of Qatar, when Riyadh alleged Doha was backing “terrorist groups”, specifically the Muslim Brotherhood.

The current diplomatic crisis is considered by many to be an effort to pressure Lebanon’s Iran-backed Hezbollah movement.

“The Saudis saw an opening to apply pressure on Hezbollah and took it. It is not so much about what Kordahi said,” Halabi said.

This is not the first time the two countries have been at loggerheads. Since the assassination of Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in 2005, and the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel, Saudi Arabia’s position in Lebanon has weakened, reflected in lower foreign direct investment and less political sway in influencing domestic politics.

Following the Arab Spring uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa, Saudi Arabia banned citizens from visiting Lebanon in 2012, causing a major blow to the country’s tourism and retail industries.

In 2017, Riyadh stated that the Lebanese government, which then had a majority pro-Hezbollah parliament, had “declared war” on Saudi Arabia. Former Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri, a longtime Saudi ally, was forced to resign by Riyadh that year during a visit to the Gulf kingdom.

If the Gulf further tightens the screws on Beirut to try and force political change, the Lebanese economy will struggle while life for expatriate Lebanese in the GCC may get harder.

“Lebanon no longer holds the special place in the region it once did,” Theodore Karasik, a senior adviser at consultancy Gulf State Analytics in Washington, DC, said. “The UAE and other GCC countries don’t really need Lebanese skill sets anymore, as they are focusing on other nationalities and their own citizens” through nationalisation programmes.

"The local outlook is that Lebanon is entering a complex emergency. It may be economically going not to Chapter 11 (bankruptcy law in the US), but straight to Chapter 13 (liquidation),” Karasik warned.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.