The killer mines of Libya: How they work, what they do

Fourteen months of fighting in Tripoli has turned the Libyan capital’s neighbourhoods into death traps.

Tonnes of ordnance remain from clashes between the Libyan National Army (LNA) and the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA), which controls the city.

Most dangerous, however, are the mines laid by LNA forces and now being extricated by GNA military engineers. More than 70 civilians, including children, have been killed by blasts, with at least 125 people wounded. Injuries include loss of limbs.

Middle East Eye showed photographs of mines recovered by the GNA to Mark Hiznay, associate director of Human Rights Watch’s Arms Division.

Much of the weaponry and ammunition left over from the clashes between the LNA and GNA dates from the rule of Muammar Gaddafi, Libya’s leader until 2011.

But Hiznay said the mines laid in Tripoli’s streets and houses were not seen in Libya until Haftar’s offensive on the capital. They were provided, he suggests, by the Wagner Group, a Kremlin-linked military contractor hired by Haftar.

“This is not Gaddafi stuff, this is Wagner stuff from Russia,” he tells MEE. “I can’t say Wagner had these on the aeroplane when they flew in. But they got their weapons from somewhere, and this wasn’t the LNA.”

PMN-2

Some of the more common mines found in Tripoli are PMN-2s, Russian-made devices that come in two colours: green and brown.

The top of the PMN has a black circle with a cross on, which is the pressure plate. These are designed to either detonate when stepped on, or with a weight release.

“These are your classic blast mines,” Hiznay says, “the ones people step on and go ‘boom’. PMNs have a fairly large explosive content for its size, so these are the types that blow the bottoms of legs off.”

MON-50 and MON-100

The MON-50 and MON-100 found in Libya come in a standard Soviet green and dark brown varieties. In the United States they are known as claymore mines.

The MON is stood vertically on its on legs. If you are stood in front of the mine then you would be faced by a slightly curved rectangle.

The device is triggered either electronically or by a tripwire. The MON explodes directionally, sending out a 45-degree blast radius and shards of metal sheet backed by plastic towards its target.

“These are particularly nasty, I mean they’re common but they’re nasty,” says Hiznay.

MONs are infantry mines, usually found on battlefields. Hiznay says: “Regular soldiers would carry these, put in front of their defensive position, and ignite if they’re under attack. And this would be a last-ditch thing to use, before they get overrun.”

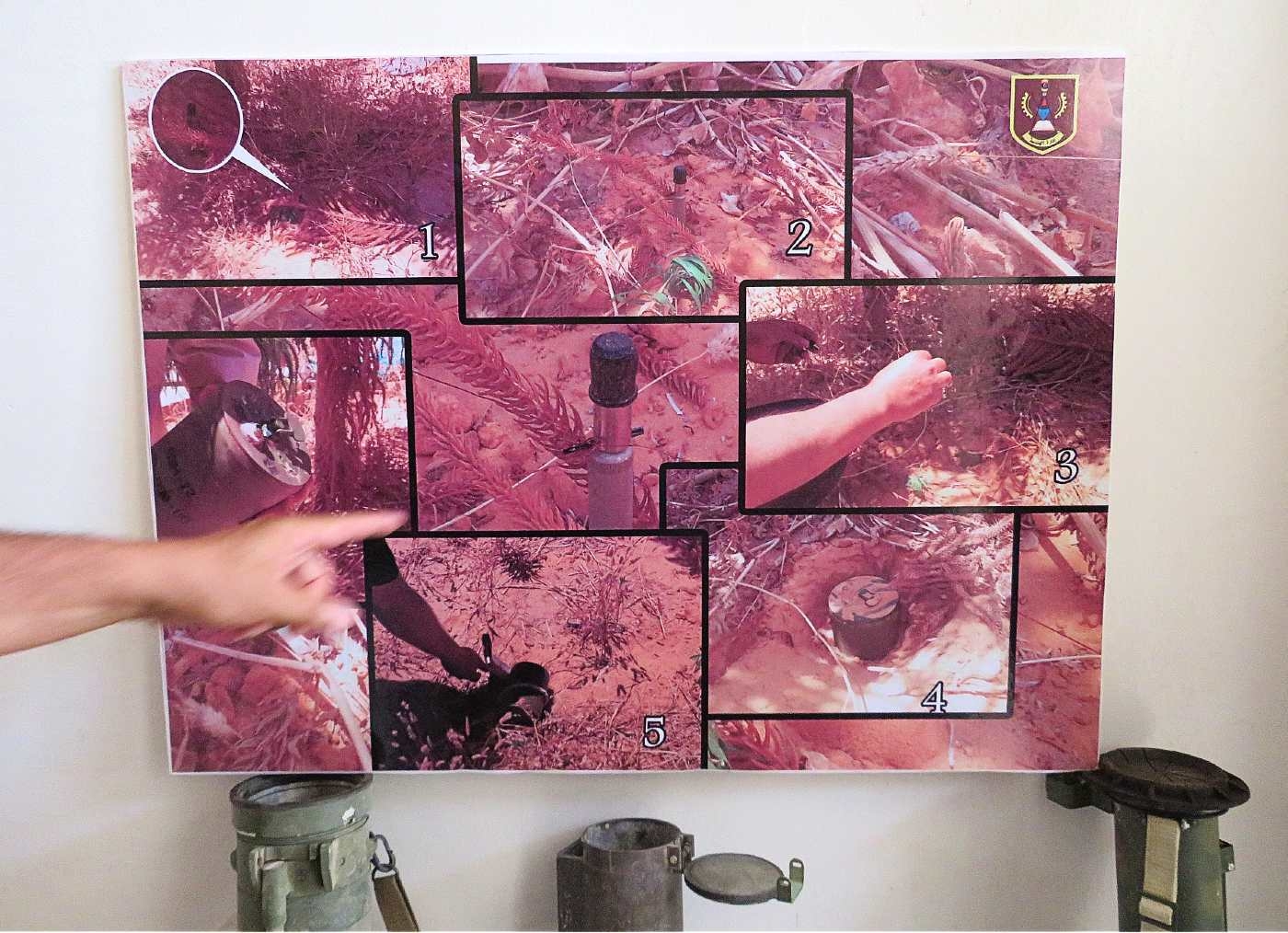

OZM-72

Some of the deadliest traps laid in Tripoli are the anti-personnel mines known as OZM-72s.

The device, which is usually olive green, is buried in the ground. When activated, it leaps a metre into the air before detonating, sending shards of its cast iron body and steel fragments out in a 360-degree blast radius.

Like the MON, the OZM-72 can be triggered by command or through a trip wire. Victim-activated detonation through tripwires is banned under international law - but manual electronic detonation is legal in the belief that the mine operator can distinguish between a civilian and a combatant.

“The Americans called them ‘Bouncing Bettys’ when they encountered the German version of this in World War Two," Hiznay says.

“Somewhere out in the Libyan desert there’s going to be the German grandfather of this device. But we didn’t see these OZM-72s in the other parts of the civil war.”

POM-2

The fourth kind of Russian mine MEE saw was the POM-2. These are anti-personnel mines that were originally designed to be scattered from helicopters, rockets and launchers.

When deployed, the POM-2 falls on the ground, rights itself on its six legs and shoots out spring-loaded tripwires. If anyone touches the tripwire, a cylinder launches one metre into the air before detonating.

Silver containers used to deploy POM-2s from trucks have been recovered from battlefields across Libya.

But bomb disposal experts have also recovered green cylinders that are used to hand place POM-2s like a grenade - a tactic employed by Wagner in a previous conflict.

“We first started seeing that in Ukraine in Donetsk,” Hiznay says, “and now it’s popped up here again in Libya.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.