Explained: Melilla, Ceuta, and the western Mediterranean migration route

On 25 July, 23 people died at the Moroccan border as they attempted to cross into the Spanish enclave of Melilla, after as many as 2,000 migrants - mainly from sub-Saharan Africa - climbed the barbed wire fence surrounding it.

Moroccan authorities said in a statement that the deaths were due to a “stampede” and that 140 police officers were wounded during the event.

Around 100 people successfully managed to cross the border into Melilla.

African Union chief Moussa Faki Mahamat expressed his shock at the “degrading treatment of African migrants” and called for an immediate investigation into the matter.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Spain’s prime minister, Pedro Sanchez, said that the country would cooperate with investigations into the deaths of the migrants and said three enquiries had been opened: one by Spain's public prosecutor, another by Moroccan prosecutors, and by the Spanish rights ombudsman.

In Morocco, prosecutors are also pressing charges against 65 mostly Sudanese migrants for trying to cross the border, a defence lawyer in Rabat said.

While there have been many attempts at crossing into Melilla, Friday’s attempt saw the highest death toll for migrants during a crossing in many years.

Here’s what you need to know about the Melilla border and the western Mediterranean migration route:

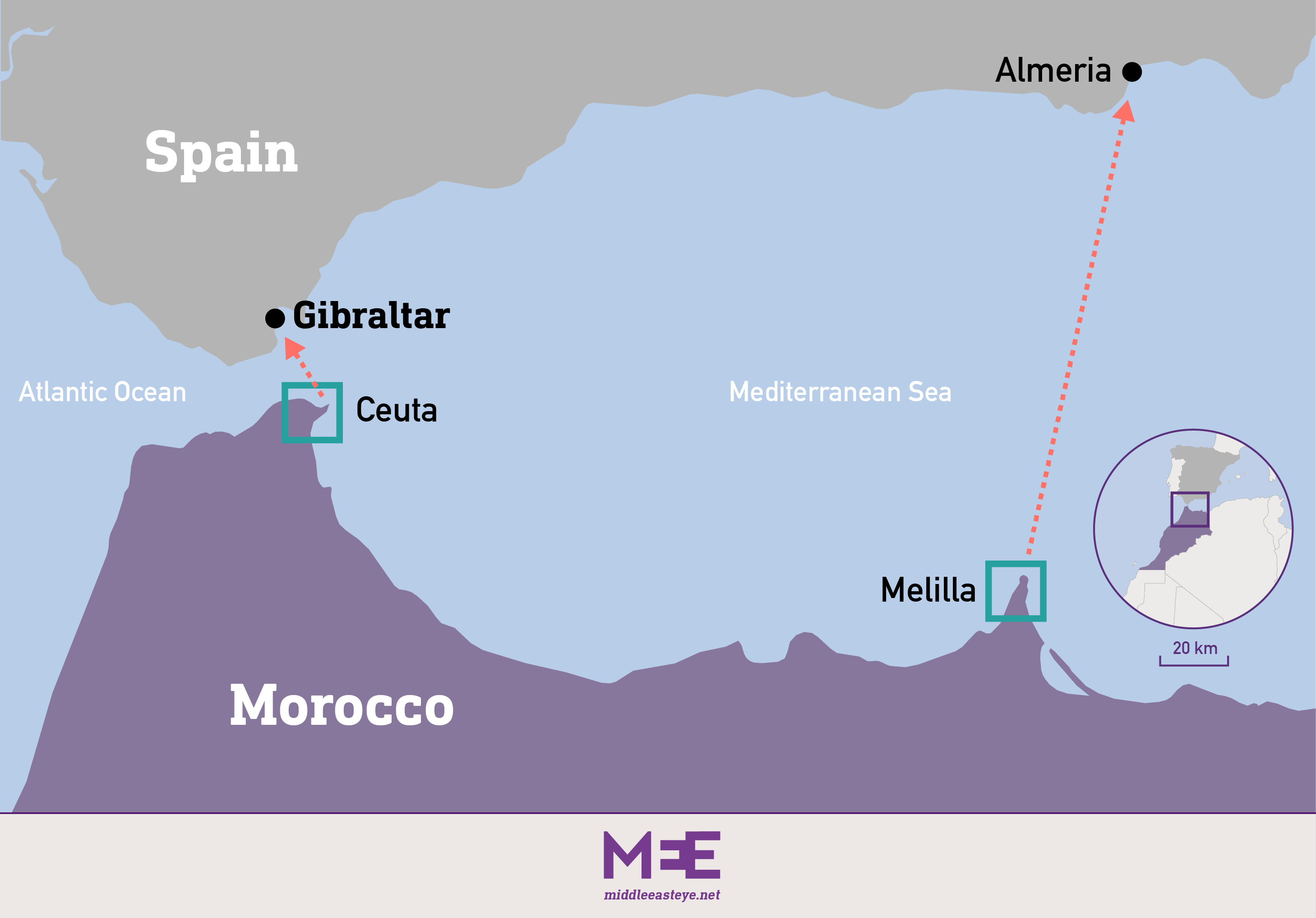

Western Mediterranean route

According to the European Union border agency, Frontex, the number of irregular migrants - those who entered Europe through unconventional means such as by small boat - using the western Mediterranean route through Spain, Morocco and Algeria, had increased in 2018 “significantly with a record of over 56,000 detections registered" that year.

In 2021, 18,466 migrants were recorded as using the route to cross into Europe.

Algeria was where most migrants depart from, with the highest majority of migrants being of Algerian nationality and the second being Moroccans.

Migrants from sub-Saharan Africa also use the route.

To stop migrants from taking this route, Morocco and Spain have developed an array of security, including 20ft razor wire fences and surveillance cameras, as well as armed officers patrolling either side of the borders of Melilla and Ceuta, another Spanish enclave.

But the borders, like many borders, have been a deadly place for migrants for decades.

According to Amnesty International, in 2005, at least 13 people died at the hands of Moroccan and Spanish police.

In February 2014, “another 15 people drowned on Tarajal Beach when Spanish police used anti-riot equipment against them”.

Melilla and Ceuta

The small Spanish enclave of Melilla and the enclave of Ceuta are the only European land borders in Africa.

Melilla first fell under Spanish rule in 1497 and Ceuta in 1668 after Portugal gave it to Spain under the Treaty of Lisbon.

But once Morocco gained its independence in 1956 after decades of rule by the French and Spanish, Spain refused to include Melilla and Ceuta as Moroccan territories.

Since 1995, both port cities have had limited self-governance as autonomous regions.

Spain refuses to discuss returning the enclaves to Morocco. It claims that the cities are integral to the country and have been for the past five decades.

But the enclaves have been increasingly criticised by human rights agencies because of the strict border policy and reports of excessive use of force from officers at the fences.

Western Sahara

For Spain and Morocco, the borders at Melilla and Ceuta have been used as a battleground for diplomatic disputes.

One such dispute is the question of Western Sahara, a territory that Spain colonised until Morocco annexed it in 1975, viewed by Morocco as sovereign territory, but supported as an independent territory by Algeria.

So in April 2021, when Spain allowed the Western Sahara independence leader Brahim Ghali to be treated for Covid-19 on the grounds of humanitarianism, the move angered Morocco.

The Moroccan government warned that allowing the Polisario Front leader to receive treatment would result in a “consequence”.

In retaliation for Ghali’s treatment, Morocco loosened its border controls in May 2021, resulting in 8,000 migrants crossing over into the Spanish enclave of Ceuta.

But, in March 2022, Spain announced a policy shift on its stance towards Western Sahara after Spanish prime minister Pedro Sanchez extended his support to the 2007 Moroccan plan of granting autonomous status to Western Sahara under Moroccan sovereignty.

Since then, the two countries have eased their strained diplomatic relations and began working together again.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.