New Zealand attacks inquiry leaves Muslims 'bewildered' and frustrated

Ever since a far-right extremist entered two mosques in New Zealand and opened fire on innocent worshippers, the country has grappled with the question of whether the attack could have been prevented.

On 15 March 2019, a gunman killed 51 people at the Al Noor Mosque and the Linwood Islamic Centre in Christchurch.

The world now knows he was a loner who spent his time on white nationalist online forums and had amassed weapons and tactical gear while taking steroids in preparation for the attack.

In August, Brenton Tarrant was sentenced to life in prison without parole - the toughest penalty imposed in New Zealand's judicial history.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

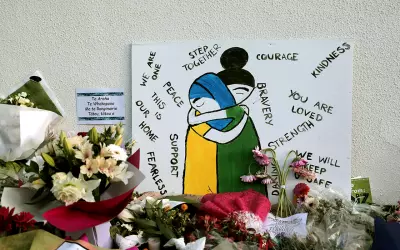

In the immediate wake of the shootings, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern called for kindness and calm.

Her compassion was lauded on the world stage and there was an outpouring of love and support for the Muslim community.

Ardern swiftly banned semi-automatic weapons such as the one used in the attack.

She launched the Christchurch Call, a platform to "eliminate terrorist and violent extremist content online", after the attacker broadcast a video of the massacre live on Facebook and published a self-styled manifesto filled with trolling and racist and far-right memes.

And she announced a Royal Commission of Inquiry - the highest level of independent inquiry - to examine the shooter, his ability to arm himself, and why he never came to the attention of police or the country's intelligence agencies.

Crucially, the inquiry was to determine whether the attack had been preventable.

800-page report

On 8 December the inquiry's commissioners delivered an 800-page report, with their findings and 44 recommendations.

Now, many of those affected, who were told their voices would be at the forefront of the inquiry process and government response, have been left feeling confused by the conclusion and sidelined by the process.

Some see the findings as the latest in a string of injustices imposed on Muslims in New Zealand.

Still, there is also a sense that the inquiry's tangible recommendations may bring about meaningful change if government and communities come together to ensure they are properly implemented.

The inquiry found failings in gun regulations and a firearms licencing system that was "lax, open to easy exploitation and was gamed by the individual".

And despite the killer seeking medical attention after accidentally shooting himself in the months leading up to the attack, he was never reported to police.

Fault was also found in the country's "fragile" intelligence agencies, which had been focusing their limited resources on the perceived threat of what the report called "Islamist extremist terrorism", while ignoring the rise of white supremacists.

Anti-Muslim bias is an issue the Muslim community had consistently raised before the attack.

Following the report's release, the police commissioner, the head of the New Zealand Security Intelligence Service, and Ardern all apologised for failings by government departments.

Ardern said she accepted "in principle" the inquiry's 44 recommendations.

Despite the shortcomings highlighted by the inquiry, it found no failures within any government agencies that would have allowed the attacker's planning and preparation to be detected.

Still, some who spoke to Middle East Eye said they believed the loss of life and trauma could have been avoided, and they do not accept the report's conclusion.

'I can't get my head around it'

Muslim community advocate and former refugee Guled Mire said the findings were "bewildering".

"There is a clear acknowledgement in the report around the systemic failures, yet there is no sense of accountability in terms of who's responsible for that, and what are they going to do about it," he said.

"I haven't been able to get my head around it."

Aya al-Umari, whose brother Hussein al-Umari was killed in the Al Noor mosque shooting, said the findings had validated what she already knew: "Institutional prejudice and unconscious bias contributed to what we saw on 15 March."

Had there been tighter controls and if unconscious bias didn't exist in society, Hussein might still be alive, she said.

Exhausted community members said they gave their time, expertise and emotions in the wake of the attack, and they had been looking for the inquiry to deliver answers.

Now, the lid has been lifted on the anger and frustration they held back for the past 21 months.

Mire said the findings were "predictable", given the limited scope of the inquiry and the priority and protection given to government agencies throughout proceedings.

By contrast, many feel Muslim communities were not at the heart of the process.

It took four months for the commissioners to meet with Muslims. And while there was a Muslim advisory group, some said it was "tokenistic".

Law student Sondos Qur'aan, who was part of the Muslim reference group, said the commissioners had genuinely tried to engage with anyone who wanted to be heard, but they were limited by the scope of the terms of reference set by the government.

Some have criticised the lack of police accountability. A police review said the response was "exemplary", a term at odds with the traumatising interactions described by survivors and victims' families.

On top of this, there has been no commitment to reparations, as well as complaints that the process lacked transparency, with much of the evidence suppressed.

Mire said it was hard to have faith in the findings and recommendations without trust in the process.

Following the report's release, Ardern thanked community members for their input and said practical actions could now be put in place to protect, care for and look after everyone.

"In the wake of such pain, I know that has been one of your goals. Now it's up to all of us to make that a reality," she said.

Those who felt let down by the inquiry, however, said Ardern's actions did not reflect her kind words.

"You just want to move forward and look at the future. But we can't look at the future without acknowledging this critical failure from a government that was supposed to be acknowledging us, and hearing our voices," said Mire.

Still, others said that despite the shortcomings of the inquiry, the focus now must be on looking ahead.

"I'm of the personal belief that, no matter what the findings were going to be, there's no way we can go back now and change everything that happened and bring back the 51 lives that passed away," said Qur'aan.

Ethnic affairs ministry

Recommendations made by the report include the creation of a new national intelligence and security agency, changes to firearms licensing rules, and reforming hate-speech laws.

There will also be a new ethnic affairs ministry - something that's long been promised by the government.

The ministry will replace the under-resourced and under-performing Office of Ethnic Communities, and will be responsible for improving social cohesion.

"Societies that are polarised around political, social, cultural, environmental, economic, ethnic or religious differences will more likely see radicalising ideologies develop and flourish," the report said.

"Efforts to build social cohesion, inclusion and diversity can contribute to preventing or countering extremism."

Qur'aan told MEE that Muslim communities were committed to social cohesion, but the country at large also had a role to play in embracing inclusivity.

"This is not something that we, as a Muslim community, need to advocate for. This is something all of New Zealand needs to advocate for," she said.

"It's about all New Zealanders - regardless of their ethnic background or religion - feeling safe here, feeling like they belong here, feeling like there isn't a 'they' or a 'them'; that we are all considered Kiwis, and we don't have to validate our position in this country."

The inquiry wasn't just for Muslims, she said.

"I think it was for everyone that's ever felt like they didn't belong in New Zealand."

Al-Umari and her family are still grieving the loss of her brother.

"No mother or father should have to bury their child in this manner," she said.

She voiced hope that new controls will help prevent similar attacks in the future.

Al-Umari said she hoped other countries may learn from New Zealand's response to the attacks, "not just at a government level, but an individual level".

She added: "We each play a part in reducing our unconscious bias that escalates to such hate crimes."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.