Nowhere to run: The Yemenis stranded in their own country

TAIZ, Yemen - When conflict and economic disaster befall a country, populations often flee, either to save themselves or in search of a better existence.

Millions of Syrians, for example, have arrived in Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon and elsewhere since war broke out in 2011.

Not so in Yemen. Neighbours including Saudi Arabia, Oman and other countries refuse to accept the vast majority of displaced Yemenis through official channels, amid fears that it would result in a massive influx.

It's impossible to enter Saudi Arabia - which has led the coalition attack on Yemen since 2015 - as a displaced person

It has left thousands of Yemenis stranded - or else turning to people smugglers.

Wadei al-Adimi, 28, an unemployed graduate from Taiz University, decided his best option was to go and live with his brother, who has been resident in Saudi Arabia for seven years.

But it’s difficult to get a worker visa and impossible to enter the kingdom - which has led the coalition attack on Yemen's Houthi-controlled areas since 2015 - as a displaced person.

So Adimi turned to the smugglers after his brother sent him $2,000 to cover the fees and associated costs for the journey.

"I travelled to Shabwa province,” says Adimi, “and there a friend recommended a smuggler who takes people from Shabwa to Jeddah in Saudi Arabia. I travelled with 11 others in the same car."

Adimi said that the smuggler, who is legally allowed to enter Saudi himself, took them along rough mountainous roads, then stopped and asked the passengers to walk five kilometers alone across terrain inaccesible for vehicles. He then met them on the other side of the border, out of sight of checkpoints.

Some customers of the smugglers are less fortunate: they might get lost in the mountains or be discovered by Saudi patrols, who fire upon them if they try to escape.

"The smuggler comes from to an area in the border between Yemen and Saudi," says Adimi. "He is an expert in smuggling, so he could save us from the borders' guards and they did not see us."

Eventually Adimi was met by his brother in Jeddah, who then took him to the immigration authorities. He was given a visitor visa once the pair explained that Adimi had fled the war in Yemen and that his brother would support him. Many Yemenis without such guarantees are deported back across the border if they are discovered by the authorities.

"Smuggling is always dangerous and we took a risk to reach Saudi Arabia," says Adimi. "But the Saudis appreciate us and they did not bother us when we arrived."

The cattle boat to Djibouti

Yemen is one of the poorest countries in the world, ranking 160 out of 188 entries on the United Nations Human Development Index.

Since conflict erupted in Yemen in March 2015, Yemenis, Somalis and others have fled for the Horn of Africa, including Djibouti, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan, as well as Saudi Arabia and Oman.

The UNHCR said in October 2017 that 190,352 people have arrived from Yemen in neighbouring countries, often in desperate conditions. An estimated two million have been driven from their homes and are internally or externally displaced – but an estimated one million have attempted to return home, even though it is not safe, according to UNHCR.

What happened to Wadei al-Adimi was fairly straightforward: he is a young single male with no dependents, access to money and someone to meet him at his destination. It is much harder to leave Yemen with your family unless you are an official or very wealthy and can travel through airports.Where Yemenis have fled

Source: UNHCR, 31 October 2017 (Sudan 30 September 2017)

- Oman: 51,000

- Somalia: 40,044

- Saudi Arabia: 39,880

- Djibouti: 37,428

- Ethiopia: 14,602

- Sudan: 7,398

Atif Galal, 30, a father of two children, worked in marketing until war broke out and he lost his job.

"When I lost all hope of finding work, I thought about emigration,” he said. “Early in 2017 I contacted friends in Djibouti to look for work and they promised me proper work," he says.

So in March 2017 Galal withdrew cash he had saved in the bank during peace time, said goodbye to his family and left Taiz for Aden.

“From Aden I went with a ship of cattle to Djibouti and then a friend took me to my new work in a shop in Djibouti.”

Financially, Galal is now better off than he would have been back home, although he is unable to pay for his relatives to travel and join him, instead sending money transfers to pay for their food. "My new work is fine," he says. "I met many Yemenis in Djibouti who have fled the war during the last three years."

Then there are those who want to leave Yemen – but cannot.

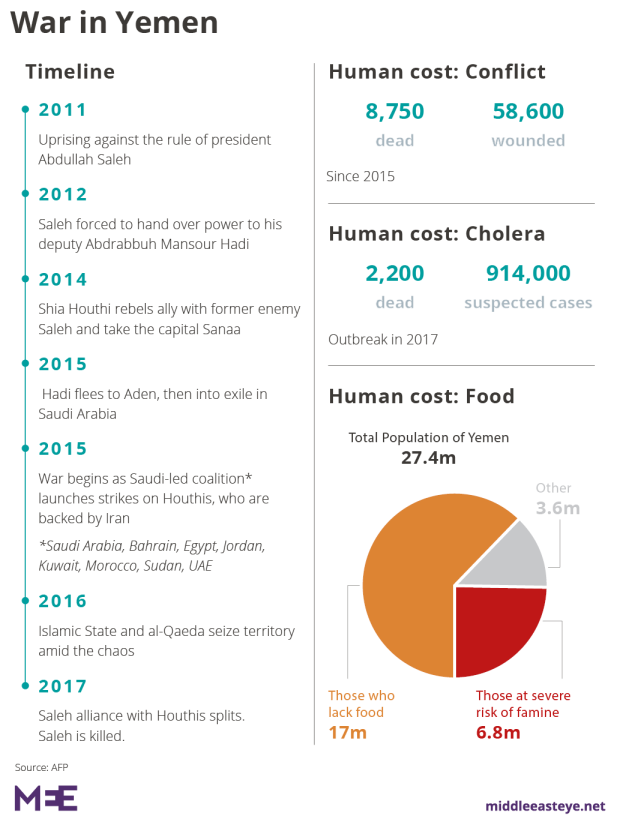

Most Yemenis are poor, certainly by the standards of other countries in the region. An estimated 20.7 million people of a population of 28 million need some kind of humanitarian or protection support: seven million people do not know where their next meal is coming from and are at risk of famine, according to the UN's humanitarian arm UNOCHA.

With barely enough money to help their families survive, paying for even an individual to travel abroad is near impossible.

He hopes to leave Yemen – but it’s unlikely to happen.

"Emigration is the dream of all the young people in need in Yemen,” he says, “ but only the rich can achieve it. Meanwhile we hardly have enough money to buy food and have no way to leave Yemen.

"Poverty forces us to live under the war and the economic crisis that has made people only think about food and nothing else.”

Yes, Azazi said, he had looked for a way to leave, but the cheapest trip costs around $1,000 per person, money he simply does not have.

"If I had $1,000, then I would open a small business in Yemen. Then there would be no need to risk myself with smugglers on the borders. The $1,000 is in itself a dream to have."

Those prepared to stay

Not everyone who is young wants to leave the country. Those with jobs tend to want to stay, despite the war.

Akram Yassin, 39, works as a distributor of cosmetics in Sanaa. He is happy with his work, has not thought about emigration, although he does admit, "If I do not have a job, I would think about leaving Yemen."

He says that the economic crisis is more dangerous than war, as the severe downturn has affected everyone while the conflict usually targets people in specific areas. "We can live under war. But needy people cannot live amid economic crisis. That is why those in need want to leave Yemen."

Fadhl al-Thobhani, a social expert and professor of sociology at Taiz University, said that the situation in Yemen is not like that in Syria or other countries, where those leaving have been officially welcomed by their new hosts.

"If Saudi Arabia opened its borders to Yemenis, we would see millions of Yemenis leave and head towards Saudi. This would affect Saudi negatively, so it is normal that neighboring countries will open their doors only for specific people."

“In Syria, both the needy and rich families can leave their country, but in Yemen only the rich ones can leave, while the poor have to live amid war. Poor people are the main victims of the war."

Adimi says he is grateful to the Saudi authorities for not expelling those Yemenis who have passports and someone to guarantee them.

And he hopes that those desperate to leave will be able to do so. “Life in Yemen means destruction of the future. I advise anyone who is young and desperate to work hard to leave Yemen and build their future."

For many stuck in Yemen, it’s an impossible hope.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.