Qatar: Pandemic and short-staffing woes leave restaurant industry struggling to stay afloat

With the country set to host the FIFA World Cup in December 2022, restaurants in Qatar had been getting ready for a big increase in customers, but the Covid-19 pandemic has only been one factor making it hard for them to prepare.

The pandemic has permanently changed the dining and takeaway scene in the country, said OTK Raheem, a partner at Jawahar Restaurant in Doha’s al-Bidda park.

“Neighbourhood restaurants used to command unflinching loyalty in the past, which is no longer the case,” Raheem told Middle East Eye.

A severe shortage of migrant workers, hectic road-digging, and the high costs of raw materials are also troubling the restaurant industry.

While the difficult circumstances have severely affected many restaurant owners’ profit margins - if not caused outright losses - their hopes remain pinned on the World Cup to turn their fortunes around.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Yet the increased demand for workers, as well as the lifting of longstanding and draconian labour restrictions, have meant more freedom for migrants to switch jobs in search of better working conditions.

The impact of the pandemic

Restaurateurs were clueless when the pandemic first struck, relying on deliveries and takeaways to keep business running.

“[We were] unable to know when the crisis would end, and we sent off workers who were not required at that moment,” a restaurateur in Doha’s Bin Mahmoud neighbourhood, who requested anonymity, told MEE.

His restaurant used to employ 45 workers, including contractors, before the first coronavirus lockdown. Now, only 18 members of staff remain.

Many workers said some restaurants treated them mercilessly during the lockdown, with some of those who were laid off left to fend for themselves without shelter or food.

Now, visa processing for new foreign workers - who form the backbone of many industries in Qatar - has become a far slower process than it used to be, making it harder for restaurants to take on much-needed new employees.

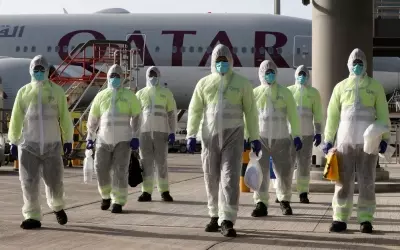

Bringing in new workers now involves a four-month wait and new expenses, with one human resources manager for a luxury hospitality firm telling MEE that airfare and hotel quarantine costs amounted to $3,570 per worker.

A cheaper quarantine dormitory for low-paid workers at Mekaines, 43 km outside Doha, charges $405 per worker, a quarter of the cost of a hotel quarantine. But unlike hotels where travellers are quarantined for two days, a 10-day stay is mandatory at Mekaines.

At the time of writing, there were no vacancies at Mekaines until 10 November.

The Bin Mahmoud restaurateur said he spent $6,317 in total, including airfare and Covid-19 vaccines, for seven workers returning from India, Sri Lanka, and Nepal.

“Many workers’ home countries don’t have efficient vaccination programmes. So, if we ask them to come immediately, we have to pay for their vaccination at private facilities,” the restaurateur said.

Workers from India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh, and the Philippines seeking a Qatari visa must get through a vetting process in the Qatar Visa Centers in their home countries. But wait times are long and visas hard to get, according to Shamsudheen Purameri, an entrepreneur opening two restaurants in Madinat Khalifa.

“We apply for 30 visas but get only one,” he told MEE.

The pandemic has also affected other restaurants that didn’t jettison their staff.

“Unlike most restaurants, my workers hadn’t gone on vacation for two years because of travel restrictions,” a restaurant partner in Doha’s Ain Khaled district told MEE. “But when things eased up, everyone went at once. Now we have reduced working hours.”

Worker shortage and roads under construction

The slow pace of visa processing has been viewed by some as a sign that Qatari authorities are deliberately seeking to reduce the number of foreign workers - who make up an estimated 88 percent of people in the country - ahead of the World Cup.

As of August, the latest figures on Qatar’s population were at their lowest since 2016.

That same month, a circular sent by a roads project manager for the public works authority, Ashghal, urged engineers, contractors, and consultants to “reduce inessential expatriate workforce…between 21 September 2022 and 18 January 2023,” citing a labour ministry directive.

Some believe a similar policy may be affecting foreign workers in the service industry.

“The shortage of staff affects the consistency of food and services,” Purameri said. “It affects the morale of the existing staff. Phone attendants get tired of complaints, and they leave when the stress is unbearable.”

Purameri says he has hired workers locally out of desperation, offering them double or triple the usual salary. “When the existing staff knows this disparity, they feel dejected,” he said.

Some business owners said they’ve had to get more involved in menial work, waiting tables, and working in the kitchen to make up for the lack of staff. “Our full-time presence on the premises prevents us from concentrating on other things, like liaising with the government,” Purameri said.

Meanwhile, the construction work ahead of the World Cup has had a negative effect on the restaurant industry, with extensive and lengthy road repairs limiting the presence of potential customers in some areas for months on end.

In the neighbhourhood of Bin Mahmoud, for example, roadworks ongoing for 11 months have left some with little choice but to close up shop, with the pandemic and construction also affecting income.

“Nobody has these kinds of reserves to run a business for two years,” the Bin Mahmoud restaurateur said. “We wish the authorities were a bit more considerate.”

Since roadworks have affected the number of walk-in patrons, delivery has been the lifeblood of many restaurants.

But once again, restaurants have struggled to find delivery drivers willing to work for the lower wages offered by restaurants.

“We earn over $825 working for app-based delivery companies, but restaurants offer only half that wage,” a delivery driver for the Talabat app told MEE.

But restaurateurs said they were reticent to resort exclusively to app-based delivery companies, arguing that the margins that these organisations charge eat up their profit.

Increased competition and rising costs

Paradoxically, the pandemic led to an increase in the number of restaurants opened in Qatar - creating more competition.

“During the first lockdown in 2020, three types of businesses - groceries, restaurants, and pharmacies - were allowed to run without interruption, so many businessmen and professionals from other sectors began investing in restaurants,” the Ain Khaled restaurateur explained.

“They lured our workers with higher pay,” he added. “When they failed to make the profit they had hoped for, they introduced cheaper combos in the menu to drive sales without considering the cost.

“Eventually, they closed shop, and everyone - them, us, the lured staff - suffered,” the Ain Khaled restaurateur added. “Now I get at least three phone calls daily from people offering to sell their restaurants.”

Meanwhile, a shipping container shortage expected to continue until 2023 has driven up the prices of packaging, with the cost for containers rising from $3,000 to $9,000 since the beginning of a pandemic.

Fresh produce costs have also risen during the same time frame. “A box of cucumber that once sold between $3.85 and $5.49 has now cost us $14.56 for some time,” Raheem said.

A karak tea chain owner said his supplier of disposable cups no longer gave him price quotes. “They know we won’t buy them if we know the price in advance, because they know we can’t sell tea for $0.27 in that cup,” he told MEE.

Yet restaurateurs said they were reticent to increase the prices on their menus to make up for the costs of ingredients, fearing negative comments from a growing number of so-called “foodie” groups online.

Difficult working conditions

Purameri lamented the days of the ustads, the kitchen supervisor cum master chef in the Arabian Gulf restaurants. “They were pious and supportive of business owners. Now younger replacements are short-tempered and ever-ready to jump ship in times of crisis,” he said.

But the complaints of restaurant owners have not been well received by Qatar’s migrant workforce - for whom the ability to change employers is only a very recent development.

'Only people in extreme financial hardship or those with a passion for for it will stay in kitchens'

- Mohammed Ali, restaurant worker

A 2020 change in the country’s labour law finally put an end to the notorious kafala system’s most stringent restrictions, which had tied workers’ migration status to a single employer, creating a system rife with abuse and exploitation.

While the business owners and workers MEE spoke to said the pay for restaurant workers they knew was above the minimum wage of $274.67 per month, several current and former restaurant workers told MEE that kitchens were difficult workplaces.

“Exposure to smoke and steam, shifts lasting up to 14 hours, and no holidays except annual vacation are the norm in Gulf countries,” Mohammed Ali, who worked for two decades in several restaurants across the Gulf, told MEE. “Only people in extreme financial hardship or those with a passion for it will stay in kitchens.”

The grueling pace of work leaves little time for rest and leisure.

One kitchen staffer in Doha’s Matar Qadeem district who requested anonymity told MEE he had never had the time to visit a picnic spot or take a walk along the waterfront in the six years he has lived in the Qatari capital.

“Showering and sleeping are my only concerns when done with a day’s work,” he told MEE. “When I’m sick, I take a (paracetamol) tablet and go to work.”

“But a job is a job,” he added, saying that working conditions in restaurants remained somewhat easier than in construction or private security.

For some workers, restaurant owners need to do more than simply talk about how much they respect their employees if they don’t want them to go elsewhere.

“But that respect hardly translates into better working conditions or pay,” Ali said.

“They sweet-talk us and make empty promises to keep us.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.