The Rabaa massacre five years on: Doctors haunted by memories of victims burnt alive

Five years ago, Fatima Yehia and Hatem Mohamed volunteered as field doctors at a number of sit-ins that were violently dispersed by police and army forces in the crackdown that followed the 2013 coup.

Like many other medical professionals who volunteered to save lives in the bloody events of July and August 2013, they say they still struggle with survivor’s guilt five years later.

Hospitals should be sacred, injured should be sacred, the right to transfer patients is sacred. Life is sacred. This was shameless

- Fatima Yehia, volunteer field doctor

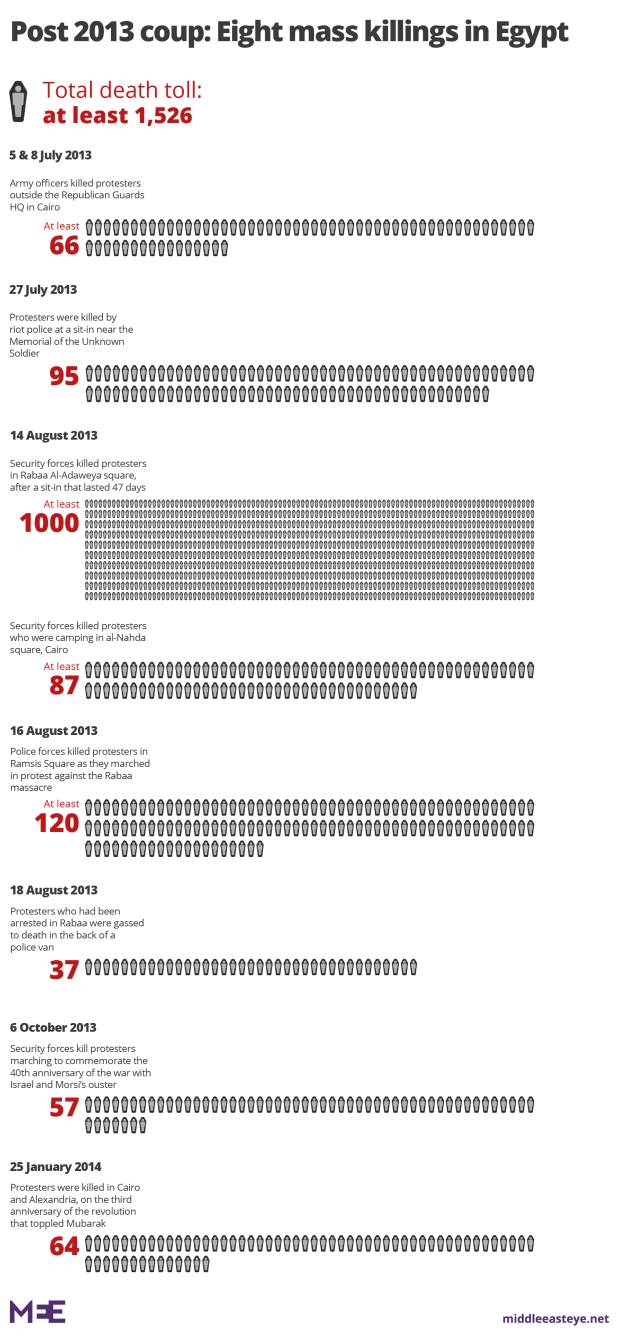

That summer, police and army forces killed at least 1,150 anti-coup protesters in what was described by Human Rights Watch (HRW) as “crimes against humanity".

To Fatima, a neurosurgeon, Rabaa was not her first encounter with deadly violence. She had already witnessed two incidents of mass killings in July alone, and volunteered as a field doctor to treat the injured protesters.

Rabaa, however, was “the worst of massacres".

Rabaa is often described as the event that marked the end of the Arab Spring, and the worst incident of a mass killing of demonstrators in modern history.

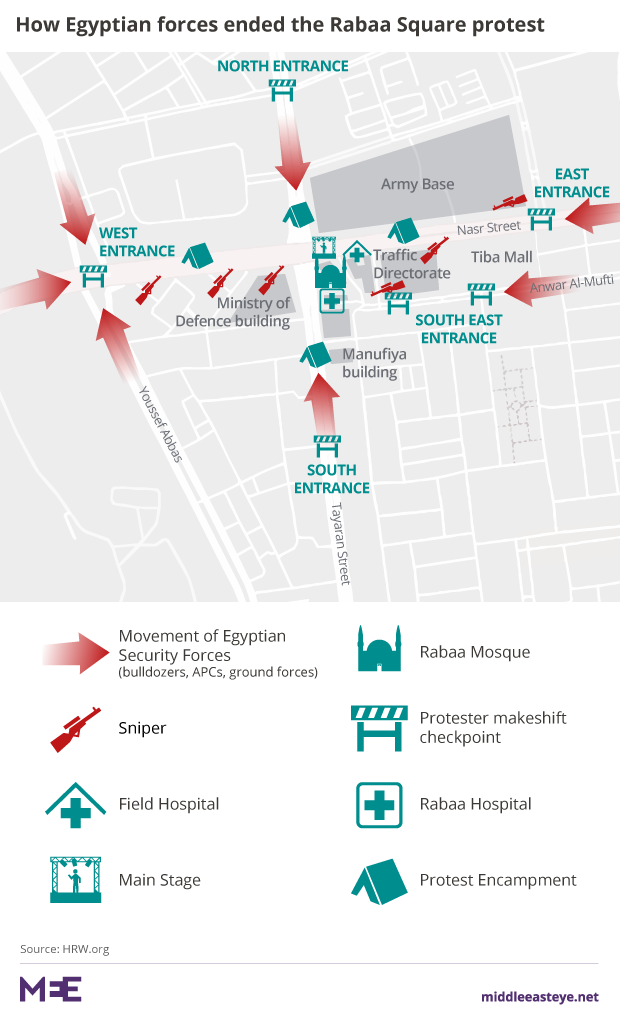

At the time, the Egyptian government alleged that security forces were responding to violence, including gunfire, from protesters. HRW's investigation into the report found that, in addition to hundreds of protesters throwing rocks and Molotov cocktails at police once the assault began, demonstrators fired on police in a few instances. Protesters, however, were overwhelming peaceful.

According to the official Forensic Medical Authority, eight police officers were killed during the Rabaa dispersal.

But HRW concluded that the protesters’ violence in no way justified the deliberate and indiscriminate killings of protesters largely by police, in coordination with army forces.

On 5 and 8 July, soldiers opened fire at protesters who were staging a sit-in outside the Republican Guards headquarters in Cairo, where the deposed President Mohamed Morsi was believed to be held by the army. They killed a total of 66 protesters, most shot in the chest or head.Then on 27 July, 95 more protesters were shot dead near the Memorial of the Unknown Soldier (also known as the Manassa Memorial), located on the road leading to Rabaa Square.

Despite those deaths, what happened on 14 August 2013 was beyond the imagination of anyone who camped there for 47 days after Morsi was ousted from power.

Not only did security forces target protesters “systematically” and “indiscriminately” as HRW said in its report, they also targeted the field hospital where hundreds of injured protesters received emergency medical care.

The Rabaa field hospital, known as the “medical centre,” was thought to be the safest refuge for the wounded and their doctors. Instead, the volunteer doctors said it turned out to be one of the most dangerous spots.

A few days before the dispersal, doctors in Rabaa had started daily simulations of emergency responses if a sudden violent attack were to occur. They had gas masks in order to work under tear gas. Most of them had not worked in conflict zones before.On that day, however, it was no longer a simulation. The attack was real.

It started at 7 am, when Fatima and her colleagues were fast asleep, thinking the day would pass like any normal sit-in day.

“I heard calls for us to get ready for work immediately. We were sleeping on the floors of rooms annexed to the makeshift hospital," she said.

Fatima’s role was to manage the incoming cases by writing a medical report and, when needed, to install Tracheal tubes to facilitate breathing.

The wounded started to be transferred to the field hospital shortly after the start of the attack. They were in the hundreds.

Most of the cases that arrived had been shot in the head or chest with live ammunition, requiring emergency operations and transfer to a fully equipped hospital.

Doctors were categorised according to their specialisations.

All injuries, without exception, were caused by deadly bullets shot with the intention to kill, the field doctors told MEE. The snipers were highly precise. Shooting at the heart, head, or the back of the legs to the main artery, causing intense bleeding.

“The snipers were professional. They knew what they were doing,” said Hatem Mohamed, an ear, nose and throat doctor who volunteered in Rabaa.

By early afternoon, when the number of casualties got beyond the capacity of the field hospitals, doctors had to prioritise.

They had run out of breathing tubes and started to use an official measure - called the Glasgow coma scale - to decide which cases were the most urgent.

According to the scale, which runs from 3 to 15, those who fell under 3 were considered dead, while those who were between 8 and 10 were considered seriously injured, but not under the threat of immediate death, Yehia explained.

“Having to prioritise cases was absolutely devastating. I felt I was part of people losing their loved ones," she said.

The place started to be packed with corpses. Volunteers started to move bodies to the garden outside of the makeshift hospital.

She saw a couple of young men carrying a friend with a broken skull and a brain held in the hands of his friend.

“Knowing I was a neurosurgeon, they begged me to rescue him. I was shocked beyond belief. I told them he was already dead," she said.

No access to hospitals

There were many people, however, that could have been saved had there been access to hospitals, Yehia said.

“We didn’t have the luxury of transporting the casualties to hospital,” she said.

Passing between the field hospital and the actual hospital “felt like a James Bond movie,” she said. Medics were moving between the buildings under intense fire.

“They were trying to prevent us from saving people," she said.

There were brief moments of halt of shooting. This is when the doctors tried to transfer people.

One of the people she tried to save was a man with an opening in his skull. She had to operate in the field hospital on the dura, the sensitive outermost covering of the brain - without anesthesia.

"I managed to stitch his injuries. I never knew if he survived or not," she said.

Next to him was a man who had a bullet in his kidney, and also potentially an injured spine. They had to decide between saving his spine or his life.

“The kidney injury was more lethal. It was an emergency, but we had to think what was more urgent than another," Yehia said.

Looking from the window in the makeshift hospital, she could see a large number of casualties in the garden. They were on a waiting list. Their families asked her to throw first aid kits from the window.

When the hospital director called the ambulance services, he was told they were forbidden from entering the square.

A friend of Fatima who worked at the Azhar University hospital next to the square took an ambulance from there, against the will of the dean, but was not allowed to enter.

So she carried the stretcher and tried to enter the square with a paramedic on foot. Security forces started to shoot at them because they were in doctors’ uniforms. They managed to reach the hospital, under the risk of death.

Attack on the hospital

The work of volunteer doctors was made even more complicated by the fact that snipers started to target anyone entering or leaving the building. The makeshift hospital was not equipped to deal with cases that required operations. An adjacent hospital was meant to deal with such cases.

It became increasingly difficult to transfer the injured between the two buildings.

Fatima recalled that a friend of hers, a doctor who was largely apolitical, heard about the dispersal in the media. He lived near the square. He hurried to Rabaa to volunteer. He was killed at the entrance stairs of the hospital by a gunshot to his chest.

As the sun started to set, doctors and patients were terrified by the sound of an explosion at the door of the hospital.

“We saw groups of officers in black uniform and face masks approaching the building. They blew up the entrance of the building, causing an earthquake-like effect. It was horrifying,” said Hatem.

Special-forces officers with assault rifles broke into the building, and ordered all medical volunteers to evacuate the building.

A Special Forces officer threatened Fatima, asking her to leave the case she was attending.

“It’s very simple. You will either leave or I will kill both of you,” she said he told her.

One of the doctors tried to take an injured young man who had fractures in his leg as a result of bullets. An officer prevented him, threatening that if he took him he would break his leg and let him lie beside him.

Until today, Fatima still wonders why the officers forced the doctors to leave the injured behind.

“Hospitals should be sacred, injured should be sacred, the right to transfer patients is sacred. Life is sacred. This was shameless.”

Similarly, Hatem said one officer pointed his rifle at his face, and threatened to kill him if he did not leave.

His wife and daughter, who were trapped at the sit-in, begged him to leave.

“I cannot explain that feeling. We left under the threat of arms and under pressure from our loved ones. I had vowed not to leave until the last injured person leaves the place. But I didn’t keep up my vow. When I remember this, I lose sleep,” he said.

Officers asked everyone to leave the building. Any injured person who was not able to walk was left behind.

As Fatima and Hatem were leaving the square, the mosque and the field hospital were set on fire.

All those who were left behind were burned, some of them alive.

“When I went to the morgue the next day, many corpses were charred,” Fatima said.

On 3 July 2018, marking the fifth anniversary of the coup, the Egyptian parliament approved a law that exempted senior army officers from prosecution for any acts committed since July 2013. That includes Rabaa and seven other mass killings.

Nearly 1,000 protesters were prosecuted and many of them received life sentences and death sentences for their role in the demonstrations that followed the coup.

Fatima struggled with survivor’s guilt after Rabaa. For two years, she lived in self-imposed solitude and refused to attend any happy events, such as weddings or birthday parties.

“I felt it was betrayal to the victims,” she said.

Hatem told MEE he had left a prominent post at a Saudi hospital in 2011 to come back to Egypt and support democracy after the revolution. But now he is living in exile in Canada.

“The dream of bread, freedom and dignity was killed on the day of Rabaa,” Hatem said.

Fatima, however, is more hopeful.

“I have a deep belief that injustice will not last. But someone has to do something. I still believe in miracles.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.