How Rabaa and its symbol changed Turkish-Egyptian relations

Nine years ago, inspired by the anti-authoritarian movements sweeping the Middle East and North Africa, Fatima and a few other youths came together to spread the revolutions' message, and warn against the crackdowns against them.

"We were a group of young activists, academics, professionals, housewives, students who were getting together to tell people about the Arab Spring in Turkey," she said.

Today, one part of their work has endured perhaps more than any other: the Rabaa symbol, a four-fingered logo that she says symbolised "one of the world's largest killings of demonstrators in a single day in recent history".

She means the Rabaa massacre, by which a protest in Cairo against the 2013 military coup that removed Egypt's first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi, was brutally cleared by security forces. Human Rights Watch estimates that at least 800 protesters, and perhaps over 1,000, were killed nine years ago on Sunday.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Fatima's logo, and what it came to symbolise, would then go on to have a profound impact, not only on Egyptian society but also in shaping Turkey.

Freedom

Then in its second year, in 2013 the Arab Spring was still reverberating around the Middle East. The intensity of conflicts in Syria, Libya, and Yemen had left thousands dead and displaced millions.

Egypt, as the region's most populous country, also became a bellwether for regional transformation and whether a democratic transition could be achieved and sustained.

"People in Turkey were confused. They were asking themselves was this a western game in the Middle East or was there a genuine yearning for democracy and freedom," Fatima told Middle East Eye, using a pseudonym for security reasons.

"We wanted to show them that this was a genuine grassroots uprising."

"Before the Rabaa massacre happened, Muslims had been gathering at Sarachane Park," said Fatima, describing a meeting point in the Fatih district of Istanbul that served as a rallying point for the city's conservatives for decades.

The six-week-long Rabaa Square sit-in, which began shortly after Morsi was overthrown by the now current president, Abdel Fatteh el-Sisi, in early July, coincided with Ramadan, adding to the heightened emotion many Muslims in Turkey and Egypt were feeling.

The gatherings at Sarachane Park became their own version of sit-ins, seeking to connect a space in Istanbul with their counterpart in Rabaa Square in solidarity.

"People were praying there, breaking fast and praying for Egypt. We also included the oppressed Muslims in China, Yemen and Palestine in our prayers," said Fatima.

The symbol

Fatima, speaking over Zoom, is still clearly emotional as she describes watching live in Sarachane Park the Egyptian army march into Rabaa Square, firing at people and setting tents on fire.

"We initially saw a protester in Egypt making the four-fingered sign in defiance," she said. "We had what we needed!"

In Arabic, the word Rabaa, which gives its name to the square, means "four". It also became a symbol of the massacre.

Previously, Egyptian revolutionaries had used the "V" victory sign as they overthrew longtime autocrat Hosni Mubarak in 2011. But Sisi's supporters now occupied Cairo's Tahrir Square and were using the same symbol, and it began to be used to legitimise the coup, Fatima said.

"So the Rabaa sign came out to oppose what was happening in Tahir Square. For us, this was a remarkable story," said Fatima. "We made the logo almost immediately. We wanted it to have meaning that would resonate with what happened in Egypt but also connect it to the wider Muslim world."

The colours chosen by Fatima, a graphic and social media designer, were no accident either.

"The yellow symbolized the vivid golden yellow dome of the Dome of the Rock" of Jerusalem, she said. "And the black symbolised the Kaaba [in Mecca] and our unity."

Fatima always intended for the symbol to transcend the borders of Egypt and Turkey, yet she was not to know that the Rabaa sign would eventually take on a new meaning and become unmoored from its intended idea.

"Our emotions were not populist, patriotic or nationalist. We were thinking about the Ummah," said Fatima, referring to the idea of the global community of Muslims connected by ties of religion. "We wanted justice."

Fatima went on: "When we saw the symbol spread, it was a proud moment for us. My Instagram, Twitter and Facebook feed became yellow and black. The symbol went beyond Egypt and Turkey. It was used as far away as Malaysia, Indonesia and also in Europe."

Closer to home, for Fatima, the coup and what happened in Egypt resonated with a darker chapter in Turkish history, particularly for conservative people.

"We suffered from coups, all political sides in Turkey, whether conservatives, secularists or leftists. It's a social memory we have in Turkey. Even if I haven't experienced it myself, my parents did, and that's part of me," she said. "We were probably the best people in the region to understand what they were going through."

Turkey's first coup was in May 1960, which led to the execution of prime minister Adnan Menderes at the hands of the military. While there have been several coups in Turkey, with the latest being the attempted takeover in 2016, what happened to Menderes and with the generals' coup in 1980, which led to political violence, resulted in a profound social and political trauma.

It wasn't uncommon to hear people compare Menderes to Morsi, expecting the deposed Egyptian president to suffer a similar fate. Morsi ultimately died in incarceration after collapsing in a courtroom in 2019.

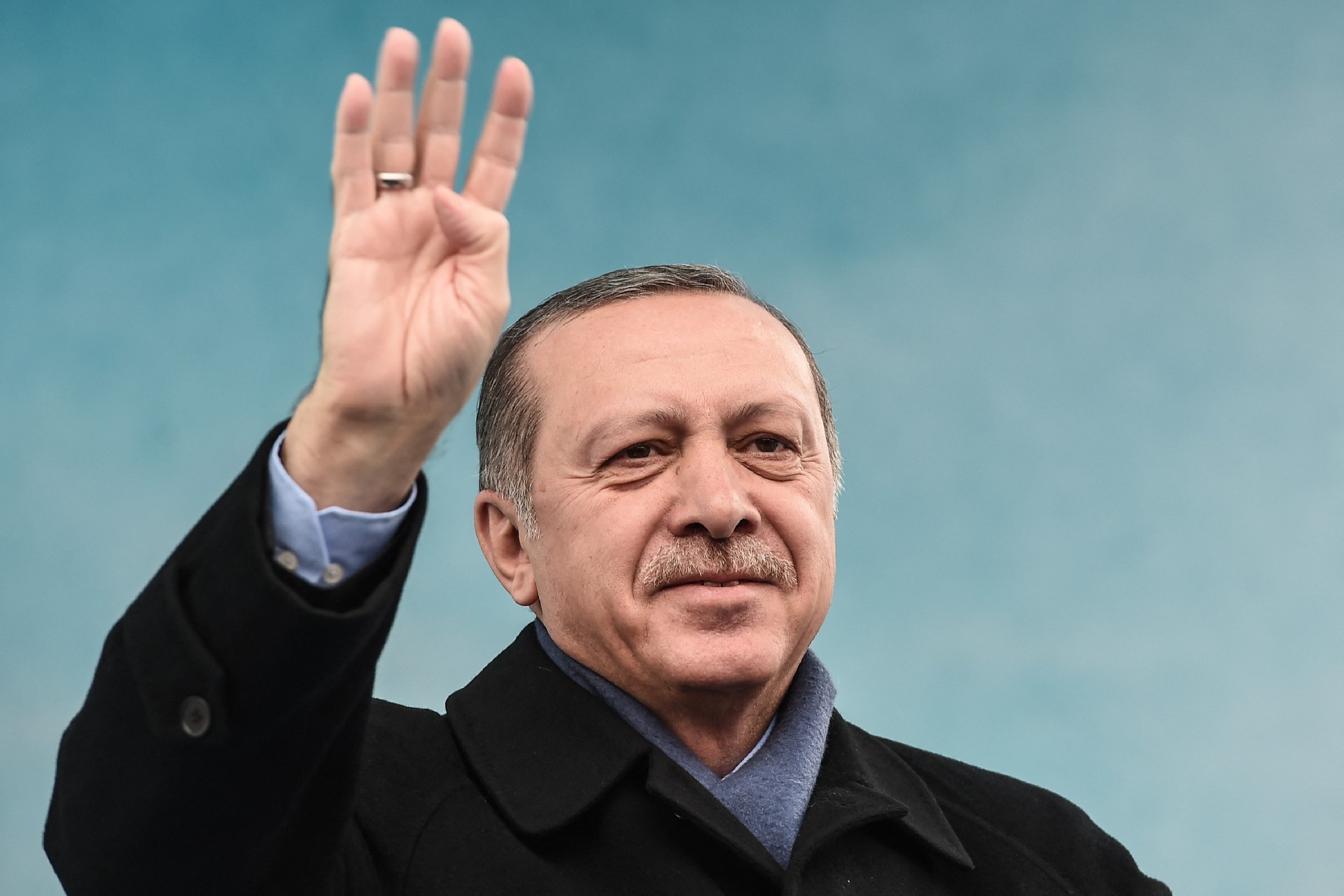

Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who is now president but at the time was prime minister, denounced Sisi.

As the Egyptian authorities cracked down on their opponents, Erdogan adopted the Rabaa sign during his rallies, often lambasting the coup.

A complete breakdown of relations between Cairo and Ankara ensued. Erdogan, who would later escape a coup attempt against himself, underlined that forcibly removing a democratically elected leader was taboo.

Affinity to the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamist political group not dissimilar from the religious movement at the roots of Turkey's now ruling AK Party, also factored in for Erdogan.

But when the 2016 coup attempt happened in Turkey, the countries' political kaleidoscope was once again re-arranged.

Changing symbols

In Turkey, symbolism and symbols matter. The anniversary of the Rabaa massacre on 14 August also coincided with the date of the founding of Erdogan's AK Party in 2001, the two becoming a singular point of commemoration.

One Turkish academic, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the AK Party's emphasis on the 14 August date was not accidental. "Why not 3 July, when the coup [against Morsi] happened?" he asked.

The meaning of the Rabaa sign and its commemoration would begin to change.

Many Egyptians knew that sign was created in Turkey. The sign in Egypt became an icon, and for many, it came to be seen as a deliberate act of defiance until the Sisi regime banned it.

What is the Rabaa massacre?

+ Show - HideOn 14 August 2013, rights groups estimate that at least 817 demonstrators - and most likely more than 1,000 - were killed as security forces cleared Rabaa square of protesters supporting ousted President Mohamed Morsi, the first elected civilian president of Egypt and a high-ranking member of the Muslim Brotherhood.

The bloodshed that occurred that day was described by Human Rights Watch (HRW) as "one of the world’s largest killings of demonstrators in a single day in modern history," as a result of "the indiscriminate and deliberate use of lethal force" against largely peaceful protesters. The HRW report concluded that the Rabaa massacre was equal to or worse than China’s Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989.

Many Turkish people now associate the Rabaa sign as an AK Party slogan.

"At the beginning, Erdogan started making the sign of Rabaa to support Morsi supporters in Egypt. However, later on, when he realized that he would not be able to make an opening with Egypt, he began to attribute a different meaning to the Rabaa sign, which was aimed at domestic politics in Turkey. This might be regarded as a U-turn for Erdogan," said another academic who wished to remain anonymous.

"The Rabaa sign continued to be used on social media profiles for a long time. When Erdogan and AK Party politicians saluted the public, they, for a long time, saluted by making the sign of Rabaa with their four fingers."

"However, even his own party's deputies (including former prime minister Binali Yıldırım) had difficulty in saying these words in order," added the second academic.

Throughout his 20 years in power, Erodgan has been effective in changing the meaning of symbols.

The CHP, Turkey's oldest political party, founded by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, had its "Six Arrows" - republicanism, populism, nationalism, secularism, autarky, and reformism - which formed the ideological tenets of the republic.

Erdogan emerged with his own four principles, in particular after the failed 2016 coup. They would be: one nation, one flag, one homeland, one state (tek millet, tek bayrak, tek vatan, tek devlet). This became the new meaning of Rabaa in Turkey.

The first Turkish academic cited above said the new meaning of the Rabaa symbol "comes from the Kemalist ideology. The AK Party, in recent years, has turned into a Kemalist-Islamist party. The four principles of Erdogan are Kemalist principles."

But there is another reason why Erdogan chose to move away from the Rabaa symbol's original meaning, said the academic. The need to repair relations with Egypt.

In recent years, the sign has not only been disconnected from its original meaning, but Erdogan has also began avoiding making the sign with his hand. For example, in September, some commentators picked up that while he was giving a speech at a rally, Erdogan avoided uttering Rabaa or making the hand gesture as he recited his four principles.

"He's not using the Rabaa sign any more," said the academic, who believes Turkey's need to pursue its interests in the gas-rich eastern Mediterranean mean good relations with Egypt have become very important to Ankara.

"If Turkey wants to be an energy hub, than one important dimension is about the Meditteranean. The Greeks and the Cypriots have successfully internationalised the eastern Mediterranean energy reserves issue. Turkey has been excluded. If Turkey wants to be a player, then it has to repair relations with Egypt," the academic said.

Relations are improving at a gathering pace. MEE reported last year that Turkish authorities requested that Egyptian opposition media channels based in the country lower their criticism of Sisi.

Earlier this year, Turkey also made a tentative attempt to appoint a new ambassador to Cairo to fill the diplomatic post left vacant for nearly nine years.

The Rabaa sign, from symbolising the 2013 massacre to becoming a Kemalist-Islamist vision of Turkey, has largely faded, if not totally disappeared, from official discourse in Turkey, apart from a few conservative circles.

"They tried to change the meaning, but I think it was a kind of short-term political move," said Fatima.

"I don't like it when it became out of context with what we created. It was something beyond Turkey."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.