Split between the Sudans, families hope for reunions after fall of Bashir

Yusra Abdallah describes her restaurant in the South Sudanese capital Juba as a sort of club for people who want to remember something of their lives - the friends and the food they have been cut off from since the country's independence in 2011.

Specialising in dishes from Sudan, the restaurant quickly became popular among the South Sudanese who used to live in the north, as well as northerners in Juba, people with parents from either side of the border and refugees, like herself, who were displaced by the Sudanese government's several wars in places like Darfur, Blue Nile state and South Kordofan.

In the eight years since South Sudan's secession, many of these people have been cut off from relatives living on the other side of the border, unable to process simple paperwork for travel and identity, even while economic and political relations between the countries continued to operate.

Their lives have often been difficult, with South Sudanese in the north vengefully dismissed from government jobs in Khartoum and deprived of their assets, in moves seen as punishment for South Sudan's 98 percent vote in favour of independence. Northerners in South Sudan, meanwhile, complain about high tax and residency costs.

But hopes for an end to their protracted problem have been raised since April, when protesters forced Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir from power after 30 years of rule during which his government was accused of violent campaigns against minorities and marginalised communities, including the South.

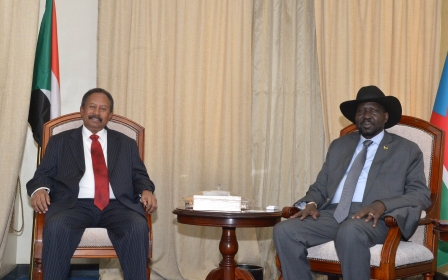

The peace talks with Sudanese rebels being held by the new transitional government, including its civilian prime minister, have been hosted in Juba, while Khartoum has also sponsored South Sudan's own negotiations to stop a civil war that has raged since shortly after independence.

"I've been living in Juba for more than 10 years as part of the huge Sudanese refugee community in South Sudan, but I also wish to see my family in Darfur," Yusra told Middle East Eye.

She fled her home as a young woman during a Sudanese government campaign in Darfur that involved violence against local communities that is being investigated for genocide. She has since settled in Juba and married a South Sudanese man, but also longs to reconnect with her home.

"It was enough for the refugees that they had to run between places as civil wars erupted everywhere, but now South Sudan has been at war since 2013, and so there was no haven for us here or there. We need the new government in Sudan to make peace and put an end to all this," she said.

Stranded

When Sudan was split in two, Mashaair Ibrahim was herself left divided.

The daughter of a northern father and South Sudanese mother, a border now sat between the two sides of her family, and there were no papers to recognise her identity, which had suddenly become complicated though she was already in her 20s by that point.

Ibrahim has lived in South Sudan since independence, though she has visited the north as frequently as bureaucracy has allowed her to reconnect with her family.

After independence, it was a South Sudanese ID that she adopted because the Sudanese government would not issue her with one.

"It's easier to do the papers in the South than in the north, but we suffered a lot as we faced difficulties in issuing our IDs on both sides," she told MEE.

'Refugees had to run between places as civil wars erupted everywhere... there was no haven for us here or there'

- Yusra Abdallah, Darfuri refugee in Juba

There are at least 1.5 million Sudanese living in South Sudan, according to community leader Hussam Ibrahim, which he believes makes them the single largest community in the Sudanese diaspora.

Some are businessmen or families like Ibrahim's, while more than 100,000 are displaced people from Sudan's conflict zones. Thousands more are known as "Bidoon," an Arabic reference to their lack of identity papers.

Businessman Idriss Ahmed, 45, had been living in South Sudan for years by the time of independence and decided to stay in Juba, but he has been left without any way of getting himself a South Sudanese identity card.

"I'm originally from north Sudan and was doing business in Juba and Wau, so didn't need an ID as Sudan was one country at that time," he said.

"After independence, I preferred to stay in the South to take care of my business, but I went bankrupt because of some problems in the market here, and now I can't return to north Sudan to do the papers, and there is no migration office in the Sudanese embassy in Juba."

The same happened to South Sudanese living in the Sudan's capital Khartoum, who have been left without work permits or any means to stay in Sudan legally.

One of those, Peter Morgan, told MEE that he cannot return to South Sudan because he has run out of money and is receiving no help from the South Sudanese embassy.

"We have been suffering from day one of South Sudan's independence because Khartoum suddenly asked us to move to the South or to pay for residency. To have residency you need to have a work permit, and you need before all that to have a passport," he said.

"I was dismissed from the Sudanese police, where I had been working for nearly 20 years, but the government in Khartoum didn't pay us any compensation, so I'm stuck here without money and forced to work as a domestic worker to feed myself."

The Sudanese ambassador in Juba, Gamal Omer, told MEE that they recognised the problem existed and more was being done to find a solution, including discussions with a recent delegation from Khartoum.

'We are now coordinating with the migration department in Khartoum to send a permanent team to the embassy to solve all these problems," he said.

Life after Bashir

Dressed in traditional South Sudanese dress but speaking fluent formal Arabic, Garang Tomas now lives in Juba but has ties to both sides. His father is from Sudan's River Nile state, but his Dinka ancestry is from Awil, just south of the border.

"For me, I don't feel like I'm a foreigner in the two sides of the big Sudan," said Tomas, who has become a well-known poet in South Sudan since independence.

"I think most of the trouble in the past was because of the Bashir government and the Islamists, who had very wrong assumptions on how to rule the country and treated the Southern Sudanese as second-class citizens."

He believes the changes in Sudan have raised optimism in the South and that people on both sides are now hoping for a healthier relationship across the border.

"Most Southern Sudanese people closely watched the revolution in Sudan and strongly supported the revolution because it was against the same regime which oppressed them before independence," he said.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.