Atmeh: The Syrian village transformed from rural idyll to Islamic State hideout

The photographers have left, and much of the world’s attention too.

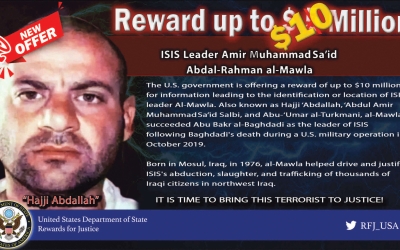

And truth be told, the residents of Atmeh, where a US raid killed Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, leader of the Islamic State group (IS), have also largely moved on with their lives.

Despite being embroiled in an event that drew world attention, the Syrians of Atmeh are all too familiar with the kind of destruction and violence witnessed on Wednesday night.

In fact, Qurayshi’s killing is emblematic of the village’s dramatic recent history and transformation.

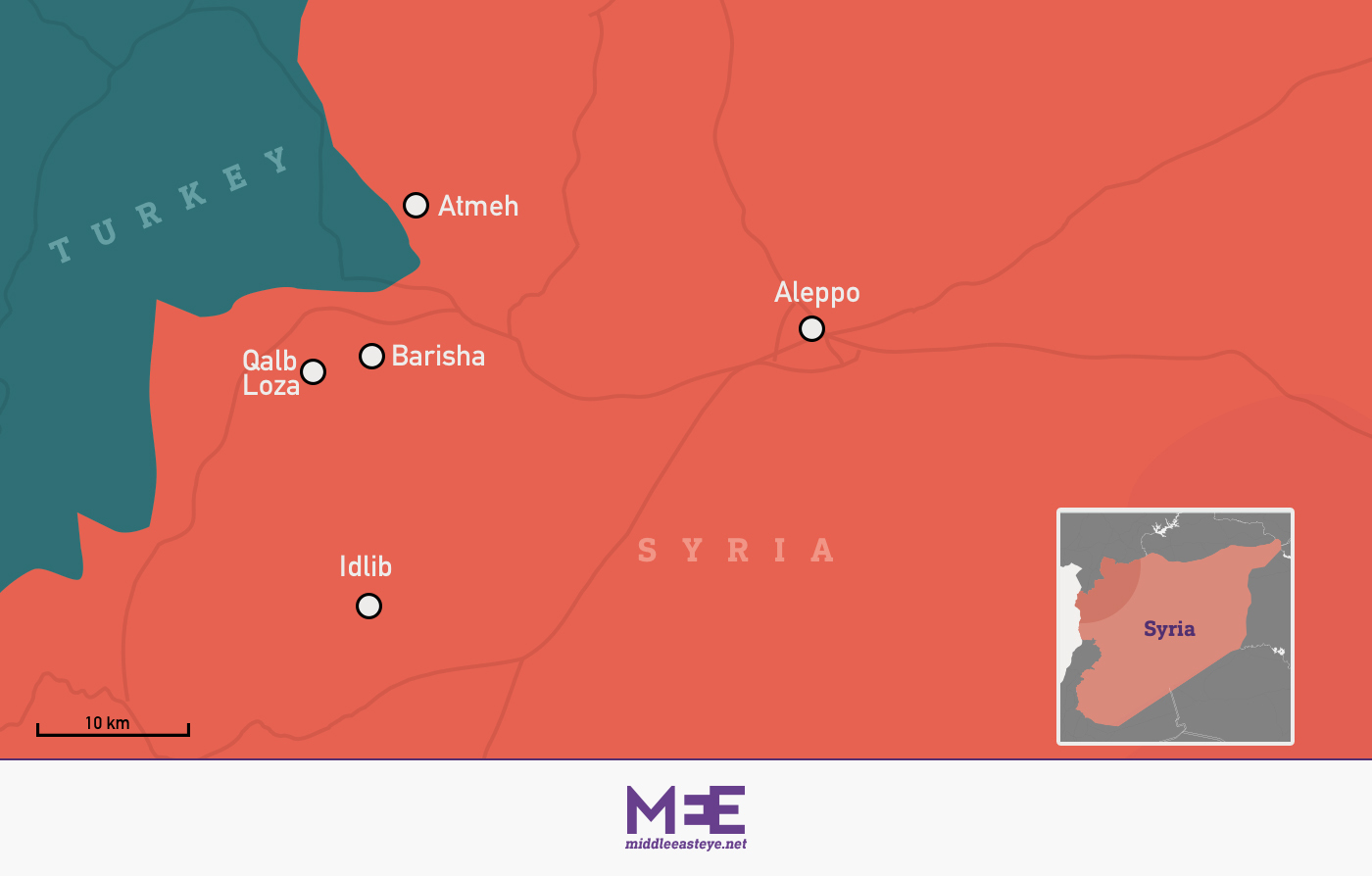

Sat just 200 metres from the Turkish border, today Atmeh is a place filled with Syrians displaced by their country’s decade-long war, navigating the mud churned up by the winter weather.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Infrastructure has had to take a leap to keep up with the new population and wartime challenges. Power cables criss-cross the streets and many homes now have solar panels.

There are hundreds of thousands of Syrians in the Atmeh area, the vast majority displaced from all over the country by war. Local resident Ahmed Najib remembers a quite different place before 2011, when only around 4,000 people lived in the village.

“They depended on the olive season, and some of them worked outside the village,” he tells Middle East Eye.

“Our village was very small, only several houses, and all the people knew each other... Everything turned around in a matter of years.”

Rebel bastion

Atmeh lies on a main route between Idlib city to the south and the Turkish-held city of Afrin to the north.

Once a calm, rural spot, in 2011 the village was, like thousands of other places across Syria, energised by anti-government demonstrations. Atmeh’s residents held protests against President Bashar al-Assad’s repressive rule.

When Assad’s forces violently cracked down on protests and sparked the civil war, rebels found Atmeh an easy place to seize and control, as there were no military barracks nearby and the village was difficult to access and send reinforcements to.

The opposition, which received logistical support through a nearby border crossing with Turkey, soon used it as an operational centre for meetings and to stage sporadic attacks on government-held areas.

This made Atmeh a target. Syrian government forces staged repeated air raids on the village, most notably in late 2012, when government warplanes bombed the rebel headquarters there. The attacks forced many residents to flee.

As the fighting expanded and the frontlines shifted to some 30km away, closer to the cities of Idlib and Aleppo, Atmeh began to feel some sort of calm once again.

Yet the battles along new frontlines sent thousands more fleeing, and many from southern Idlib province found their way to Atmeh, waiting for weeks among the olive trees for the chance to try and cross over into Turkey.

Relief organisations arrived to provide them with aid, and in this way the first displacement camp inside Syria was established on the Syrian-Turkish border in 2012.

Aid workers uprooted olive groves and erected tents instead to accommodate the waves of displaced. In 2012, the population of Atmeh camp was estimated to be around 10,000 people.

Rebels roamed the camp, both protecting it and turning it into a target.

The beginning of extremism

As the Syrian conflict developed, opposition fighters began swapping loyalty from one faction to another, often over who could pay more rather than any ideological leaning.

Some began to join hard-line militant groups, including ones affiliated with what would become IS.

By 2013, the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq (ISIS), as it was then known, had established Islamic courts in the village and arrested the leader of Suqur al-Islam Brigade, which was the rebel group that first seized Atmeh from Assad. They accused him of not supporting ISIS’ fighters against government forces, according to local media.

After that, ISIS began displaying increasingly extremist behaviour. The militants launched sporadic attacks against Kurds in Afrin, and cut down a 150-year-old tree that was reportedly used as a religious shrine by members of Afrin’s Yazidi minority.

Meanwhile, foreign fighters began flocking to ISIS’s ranks, many settling in Atmeh and neighbouring villages like Barisha.

Notably Qurayshi’s predecessor, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, was discovered in Barisha in 2019 and killed in a similar US operation. It was one of 18 Idlib villages that before the war was home to Druze Syrians, who were forced by militants to either flee or convert to Sunni Islam.

Walid, a resident of one of those 18 villages, remembers the frightening ISIS crackdown.

“They forced women to wear approved clothing and shaved the men's [traditional Druze] moustaches. Most families fled, some of them left one person in the house so that it would not be taken over,” he tells MEE.

The homes of fleeing Druze or Atmeh residents fighting in the government army were seized by the militants, and given to relatives, wives, or ISIS members.

In 2014, ISIS reached a deal with Ahrar al-Sham, another militant group, which saw it swap its positions in Idlib for the eastern city of Raqqa, which would become Islamic State’s capital. After that, Ahrar al-Sham joined Jaish al-Fatah, an alliance of rebels and militants that included al-Nusra Front, then al-Qaeda’s Syria affiliate.

'IS is rooted in the region, through the same fighters. They have nowhere else to go to, and they are still attracting local and foreign fighters from all over Syria'

- Walid, local resident

A year later, Jaish al-Fatah seized Idlib city from Assad’s forces. Nusra broke from al-Qaeda, rebranding itself, and then turned on all other rebel factions in Idlib until it had defeated them one by one. Now called Ha’yat Tahrir al-Sham, Nusra’s militants control Idlib to this day.

Despite these areas being under the control of a dizzying number of factions, many of the personnel remained the same.

Walid recalls: “They [foreign fighters] were with IS, then with Ahrar al-Sham, then al-Nusra, then HTS. Only the name changed.”

The Qalb Loza massacre of 2015 is indicative of the shifting affiliations in the Atmeh area, Walid says. In 2015, militants opened fire on Druze residents of the village of Qalb Loza after protests broke out over a Tunisian commander’s attempt to confiscate a home.

Those militants were affiliated with IS at the time but later became known as Nusra, he says.

“IS is rooted in the region, through the same fighters. They have nowhere else to go to, and they are still attracting local and foreign fighters from all over Syria,” Walid said.

Despite public animosity and rivalry between HTS and IS, Islamic State fighters began settling in Idlib when a US-led campaign began to wipe the group from eastern Syria.

Today IS members still trickle back into the province. Some are local fighters who have returned to their homes. Others are displaced Iraqis and foreign fighters and women who have managed to get out of Kurdish detention centres in the east.

Returning fighters often claim that they have retired from combat and want to return to civilian business. However, some are suspected to be sleeper cells responsible for the occasional attack.

Urban development

In Atmeh and surrounding towns like Dana and Sarmada, retired fighters have opened restaurants, cafes, amusement parks, grocery stores, and shops selling clothes and electronics. These businesses have transformed their streets and squares.

Meanwhile, Atmeh has for the past decade been a hub for relief organisations servicing the displacement camps around the village. Idlib province has a population of about three million, more than half of whom are displaced and live in tents, according to the UN office for humanitarian affairs, UNOCHA.

Commercially, the village’s fortunes were transformed when Turkish-backed rebels took Afrin from the Kurdish forces in early 2018, with a route now secured into Turkey to its west and Turkish-held Afrin to its north.

The population boom has also sparked a construction boom. Newly built flats are rented to displaced Syrians for around $200 a month, though many live in extreme poverty.

Today gunmen and militant leaders can be seen walking Atmeh’s streets. But now that they are tens of kilometres from the frontlines, they are seen locally as ineffective and problematic, sitting comfortably among displaced civilians and relief organisations while others risk their lives.

They are described by residents as leaders whose chins have never been made dirty by the dust of battle. The more that rebels displaced from elsewhere in Syria have settled in Atmeh, apparently after accumulating considerable wealth, the more this view has been reinforced.

“The village has developed a lot after the entry of the displaced. It has become teeming with life, and there are buildings and shops,” a vendor in his 50s displaced from Homs tells MEE

“I used to live in a flat, but the rent has become so high. So, I moved to live in a tent [in a camp] where most people collect leftover plastic from the village for heating,” he adds.

“Warmth is the most important thing now.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.