Impoverished Syrians suffering a Ramadan of scarce food and exorbitant prices

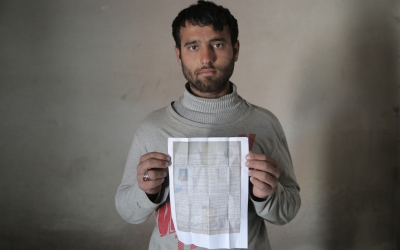

Ahmad has been selling naem, a Ramadan delicacy, for years. He makes the sweet bread himself, mixing water, flour and grape molasses, a concoction that proves popular every year with the public in Damascus.

But business is flagging, and the prices of the ingredients he uses are at an all-time high.

“This holy month I’m usually working all the time, but business is not like it was in previous years, even with the war. Ramadan never used to be like this; there would usually be some mercy in terms of prices… not any more,” he told Middle East Eye.

'This Ramadan is going to be a struggle, a real struggle'

- Ahmad, naem seller

After a winter of economic nightmares, this Ramadan promises to be the most difficult in years for Syrians, who now face a heightened financial crisis, rising prices and worsening energy shortages.

With the skyrocketing costs of groceries and goods, those fasting during the holy month are being forced to scale back their expenses, with large numbers earning barely enough income to sustain their families.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“Consumers are wary to spend, they have to budget because salaries are so low and expenses are high. Some people have even stopped eating meat because it’s so pricey, so this Ramadan is going to be a struggle, a real struggle,” Ahmad sighs.

Prices out of control

Food prices are spiralling out of control. A kilogram of green beans has reached 23,000 Syrian pounds in some areas - almost a quarter of a monthly state salary.

The average Syrian family has an expected expenditure of 2,860,000 pounds - roughly $730, and almost 40 times the single person's median income per month.

Syria's economy has been battered by a decade of war and severe western sanctions. Economic hardship has reached such a state that many now rely mostly on the hawala system and family members living abroad to keep afloat.

As the first few days of Ramadan pass, Syrians in government-held areas are faced with an unprecedented increase in the cost of living. Estimates from the Syrian economic think tank Kassioun reveal that for an average family in March/April 2022, the monthly cost of living is estimated to be around 2,860,381 pounds, an increase of 833,405 (over $200) since January.

Dealing with a 41 percent increase in living costs over three months, families are struggling to assemble their iftar meals.

Fadi, a shopkeeper near Damascus’s old city, told MEE that the economic situation has been difficult for him on the back of a very tough winter. And it’s getting worse.

“The prices are through the roof. Every Ramadan, it gets worse, but this one especially. I spent most of the last six months struggling to pay off my bills. There is no mercy on the average person, everything is so expensive,” he said.

“It’s getting harder and harder to feed my family every month. We barely have any business, and the money is like paper – you leave the house with 100,000 pounds and come back without it.”

The marked increase in prices has even covered Ramadan necessities such as dates, which have gone up in price by nearly 50 percent since last year. The maximum cost for a kilo of the most luxurious dates goes up to 40,000 pounds, double the price in 2021. A kilo of green beans costs 20,000 pounds, and the price of vegetables and chicken have all seen a spike, just in time for Ramadan.

Social media has been ablaze with despair and contempt over the situation.

“I don't know if there is logic or reason to let us understand that prices are rising in this crazy way. For example, today, if you want to make a salad, it would cost you less buying it from a restaurant,” one Syrian said on Facebook.

The economic crisis has also led to unusual measures from a cash-strapped government, which is urgently trying to raise as much money as it can. A new law issued by the Damascus governorate issues a fine of 10,000 pounds for shaking carpets in front of balconies overlooking others and throwing garbage from windows and balconies.

Even the energy sectors have been under continuous strain, with the delayed arrival of weekly subsidised petrol an indication of the severity of fuel shortages. Now, a driver who meets the subsidy criteria can access only 25 litres of state-backed petrol every 10 days, instead of every week, as was previously the case. Black market petrol is double the cost and more challenging to obtain.

The economic situation has increased people's reliance on remittances sent by Syrian expatriates to their families inside Syria. This has dramatically increased during Ramadan. It was estimated that the overall value of official remittances that reached the country during the first few days of Ramadan was around $7m per day. With this heightened demand, it is expected that official exchange companies will deal with about $420m sent to Syria this month.

Maya, who works in textiles, told MEE: “I have a brother who lives in Germany, and he sends me money every two weeks. He used to send it every month, but it’s not enough, so he sends it every fortnight. Without that, I couldn’t live here.”

Fallout from Ukraine

The global implications of the Ukraine war have already been felt worldwide, with food and fertiliser prices rising rapidly.

Since the Russian invasion, world wheat prices have increased by 21 percent, barley by 33 percent and some fertilisers by 40 percent.

Such instability adds more woe to Syria’s precarious position. Currently, 12.4 million Syrians are food insecure, an increase of 4.5 million on the previous year. This is the highest number ever recorded.

A staggering nine in 10 Syrians are now thought to be living in poverty, as their quality of life slowly deteriorates. The potential of disruption to Syria’s main wheat supplies from Russia would be catastrophic, as local production declined by over 60 percent in 2021, raising concerns of increased starvation.

Prices of wheat have been rising globally, firstly due to the transportation difficulties arising from the Covid-19 pandemic, and secondly to the Ukraine war, which threatens supply to many countries. In Syria, a kilo of bulgur - one of the country's most popular foods - has ultimately risen by 100 percent, to 5,000 pounds.

Abdul Latif al-Amin, director-general of the Syrian Grain Establishment, said authorities are attempting to compensate for the shortage of wheat by encouraging the manufacture of semolina, pasta, bulgur and other foodstuffs.

“There are contracts to supply wheat from Russia, which will arrive successively through the ports of Latakia and Tartus,” he added.

Meanwhile, the Federations of Chambers of Commerce and Industry met with the Central Bank to discuss certain foodstuffs in light of the region’s current conditions, and in anticipation of a crisis. Yet, Syrian grain and wheat supplies - which come mainly from Russia - are reportedly fine, with the Ministry of Internal Trade and Consumer Protection stating that current stocks are acceptable without reaching a supply danger zone.

“Wheat season is approaching, and our farmers will market it at better prices than market prices, stressing that there is no concern about wheat and bread,” it said.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.