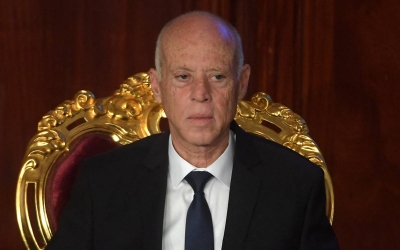

Tunisia: Kais Saied's row with the judiciary explained

Since the start of the week, Tunisia has been embroiled in another political crisis triggered by President Kais Saied's move to abolish the country's highest judicial body.

In a late-night speech on Sunday, Saied announced his intention to scrap the Supreme Judicial Council (CSM), a body tasked with ensuring the independence of the country's justice system.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

He faced an immediate backlash from Tunisian judges, the UN and world powers who called for the protection of the judiciary's independence.

Saied, a former constitutional law professor, said he wanted to "purify" the justice system, blasting members of the CSM and accusing some judges and magistrates of corruption and stalling proceedings in several cases.

He later reiterated his commitment to respecting the independence of the judiciary, promising to establish a new judicial body.

But critics are unconvinced, fearing that Saied is merely trying to evade the fallout of his announcement, while at the same time persisting with plans to undermine the judiciary.

Middle East Eye takes a look at how Saied's row with Tunisia's judges unfolded over the past seven months.

Months of wrangling

Saied's relations with the judiciary have been on edge since he consolidated power last summer.

In July 2021, Saied, who won the presidential election in 2019 as an independent candidate, suspended parliament, dismissed the prime minister and assumed vast executive powers. He has been ruling the country by decree for months, bypassing the powers granted to him in the constitution. His power grab measures were labelled as a coup by critics and opposition groups, a charge that Saied rejects.

The CSM - a body meant to remain free from political interference - was one of the last institutions in the country to remain outside his control. The council was established in 2016, after independent members were elected to it; their role is to oversee the appointment of judges, promotions, and disciplinary proceedings.

But over the past few months they have come under increasing scrutiny from the president.

On multiple occasions, Saied has accused the council of failing to resolve high-profile cases, including the political assassination of left-wing leaders in 2013.

Saied accused the council of appeasing political forces within the country, namely Islamist-leaning factions like Ennahda, the biggest party in the suspended parliament.

In December, the Tunisian Association of Judges raised the alarm, saying the president's ongoing campaign against the judiciary was turning the public against them. At the same time, cases accusing judges of wrongdoing started to emerge. At least a dozen judges were placed under house arrest as a result.

Among them is Bechir Akremi, former general prosecutor of the Tunis Court of First Instance, who was placed under house arrest days after Saied announced his power grab in July.

Akremi was accused of deliberately concealing important files regarding the 2013 assassinations of Tunisian leftist leaders Chokri Belaid and Mohamed Brahmi. He was also accused of being heavily influenced by the Ennahda party. In January, Akremi's case was dropped on appeal, over technicalities, much to the displeasure of Saied.

"Unfortunately, some judges in the courts have manipulated this case," Saied said last week. "This is not the first trial where they have tried to hide the truth for years."

Judge Akremi's case has become emblematic of the clash of power between Saied and the judiciary. Opposition groups warned Saied was trying to use the high-profile cases of political assassination as a guise to expand his powers and crush opponents.

Absence of constitutional court

Normally, Tunisia's constitutional court, the equivalent of a supreme court, would be the last line of defence against attacks on public institutions - stopping a president from dissolving parliament or going after the justice system. But the constitutional court was never fully established in Tunisia after the 2011 revolution.

Since 2014, factions in parliament have failed to agree on which four judges to appoint to the court. The eight other judges of the 12-member body were to be selected by the president and the CSM, but the parliament nominees needed to be selected first. However, the process has been derailed for eight years by arguments over the political affiliations and biases of the judges.

Now, the country's highest judicial body, which should oversee draft laws, protect parliament and hold the president to account, remains empty.

The court would have been the first of its kind in the Arab world. In April 2021, parliament tried to ratify a bill to make the selection of the first four judges easier, to speed up the establishment of the court. Saied refused to pass the amendment, saying parliament had left it five years too late. Three months later, he suspended parliament.

Since then, human rights observers have voiced concerns that the absence of the constitutional court threatens to drag Tunisia back into one-man rule.

"The institutional checks designed to keep Tunisia from reverting to the authoritarian rule it endured from independence in 1956 until the Arab Spring in 2011 are not in place," Human Rights Watch warned in August 2021.

What happens next?

Following the backlash against his disbanding the CSM, Saied seemed to backtrack when Justice Minister Leila Jaffel said on Wednesday that the body would be changed and not dissolved altogether. However, the president reiterated on Thursday that the body will certainly be abolished and replaced by another one, by decree. "There is no doubt about this choice," he said.

'The Tunisian association of judges launched a series of protests. This was supported by most of the judges' structures and its goal is to confront President Kais Saied's attempt to seize the judiciary'

- Mouhamad Afifi Jaidi, Tunisian judge

Saied promised that he does not want to interfere with the judiciary, but not everyone is convinced. Opposition is mobilising, at home and abroad.

Judges' associations, civil society groups, opposition parties, rights groups, western donors and UN agencies have all criticised his move, warning it undermines the last vestiges of official accountability for Saied.

Many judges went on a two-day strike on Wednesday and Thursday, and joined street demonstrations.

"The Tunisian association of judges launched a series of protests. This was supported by most of the judges' structures and its goal is to confront President Kais Saied's attempt to seize the judiciary, and for seizing all powers in Tunisia," judge and adviser to the court of appeal Mouhamad Afifi Jaidi told Reuters.

"It's a protest against [Saied's] attempt to impose the idea of a de facto state and no state of law, which was embodied by closing the headquarters of the Supreme Judicial Council with a mere security measure."

All this, at a time when Tunisia is facing a growing financial crisis, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are urging Saied to change course. But the Tunisian president shows no signs of doing so. He is fighting battles on multiple fronts and growing more and more isolated as the country's democratic crisis continues.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.