Explained: Turkey's battered economy and Erdogan's attempts to fix it

The Turkish lira’s steady fall against the US dollar continues, with $1 currently buying more than 17 liras - the lowest rate in the last six months.

In the last year, the lira has depreciated by 22 percent and the current exchange rate is around 100 percent higher than it was this time last year.

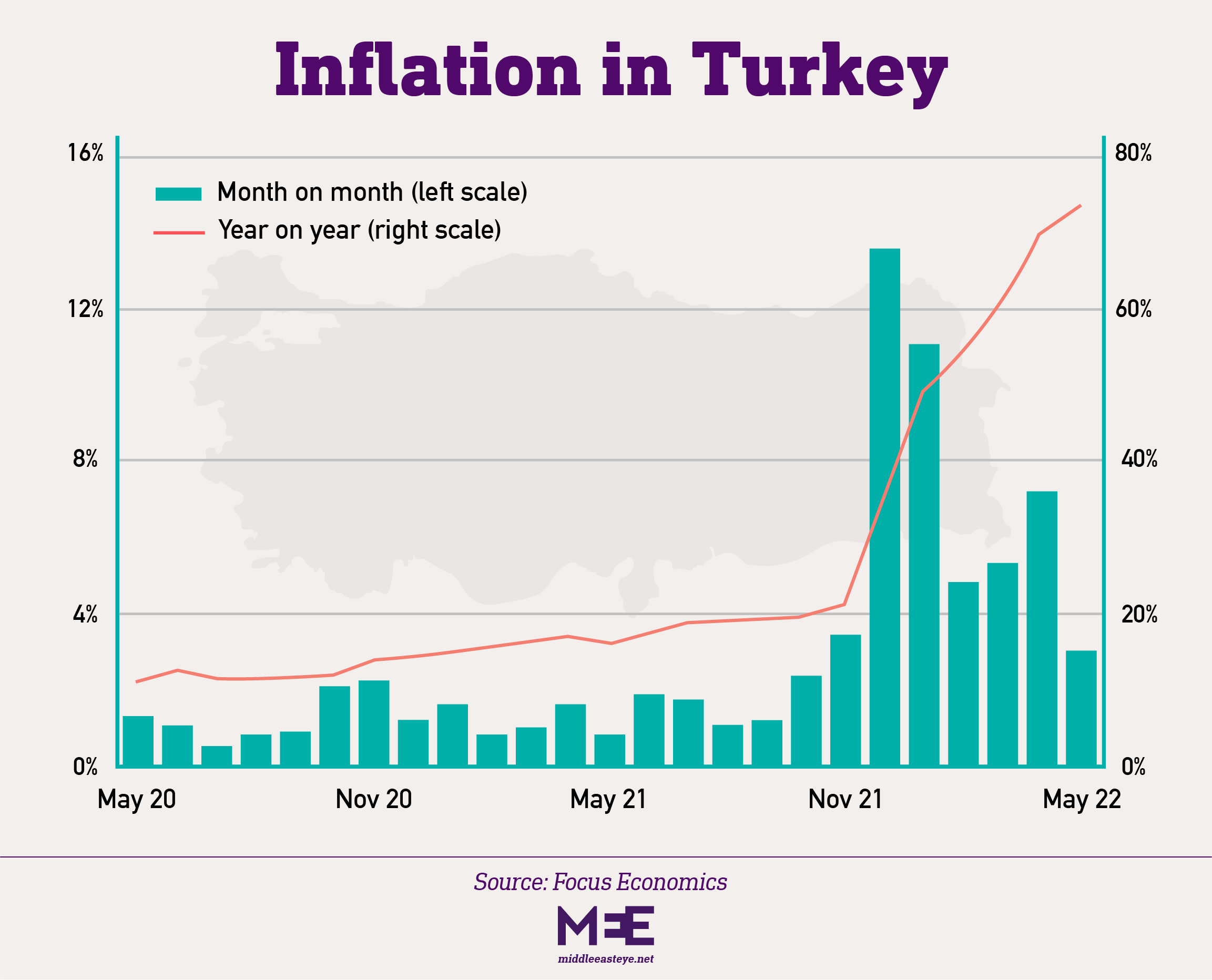

Meanwhile, annual inflation has risen above 70 percent, the worst since 1998.

Raising interest rates is often seen as a tool to reduce inflation but the Turkish government insists on keeping interest rates low and promoting exports as a way to tackle the crisis - but the trade deficit still continues to grow as energy prices hike up globally.

In response, the government has introduced several measures - alongside new financial tools - in an effort to reverse the lira’s fall and decrease the burden of inflation.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye breaks down what is happening to the Turkish economy:

Interest rates

It has become a well-known fact that President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his government ardently object to raising interest rates, despite the lira’s fall, soaring inflation, and the high amount of dollarisation in deposit accounts.

The government believes that the Turkish economic model can manage growing inflation by taking steps to protect low- and middle-income people.

Currently, the Turkish central bank is keeping the interest rate at 14 percent while inflation is running at more than 70 percent.

While other countries with much lower inflation rates choose to increase interest rates, the Turkish government believes it is possible to grow the economy and keep interest rates low. Finance and Treasury Minister Nureddin Nebati said inflation would fall next year, allowing Turkey to cut interest rates further.

While the opposition and several economists keep calling on the government to increase interest rates in order to prevent the lira’s fall, Erdogan ruled out such a move in a speech on Monday, stating that “this government will not increase interest rates".

Instead, Erdogan put forward two reasons for the high living costs: the large volume of dollars in deposit accounts and Turkey’s overreliance on imports.

Erdogan has also repeatedly promised that his government will take necessary steps to protect low-income citizens and prevent lira deposit accounts from being exchanged for dollar ones.

To this end, the minimum wage was doubled in January, while state employees received a nearly 30 percent increase in their salaries with a further raise promised in July.

Furthermore, the government introduced a measure in December aimed at stopping the dollarisation of deposits within Turkey by guaranteeing that savings accounts in lira will collect the same return as as forex markets. And if the forex markets drop below the official interest rates, the investor will still get an official interest rate return. This was intended to lure in investors without increasing interest rates.

Despite this, savings in foreign currency in Turkish banks have increased by 80 percent since June 2021, 15 percent more than lira, according to the Central Bank.

This measure managed to help the lira gain value by around 30 percent and remain stable for nearly three months.

However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent increase in the global price of food and commodities once again accelerated the lira’s decline.

Lastly, the Treasury declared on Thursday evening that investors would enjoy “state enterprise income-indexed domestic bonds” without giving further details on how this scheme would work.

Following this statement, the lira swung between gains and losses of as much as two percent - but as of Friday noon the dollar had regained its previous rate.

Appreciation of foreign currencies

Since January, the lira has depreciated by 22 percent and has been subjected to strong fluctuations in foreign exchange markets.

The Turkish government believes a weak lira offers a chance for the country to increase its exports as it becomes more competitive, and that Turkey’s proximity to international markets - such as Europe - offers a further advantage to the country's exporters amid soaring global transportation prices.

The appreciation of the dollar against the lira is both the cause and consequence of an array of problems and policies in the Turkish economy.

The soaring inflation rate and the growing trade deficit have brought about several other problems, including a dramatic increase in the cost of basic foods and house prices, which has, in turn, prompted government-imposed measures, such as low mortgage rates for first-time house buyers and additional salary increases for state employees.

However, a weak lira still means a further trade deficit as Turkey’s imports surpass its exports.

In May, according to the Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK), exports stood at $18.97bn but imports were at $29.65bn. Since the beginning of this year the gap between imports and exports has kept increasing.

Moreover, as the war in Ukraine is diminishing the number of tourists coming to Turkey, which is one of the main routes for foreign currency into the country, this deficit will grow even further by the end of the summer.

The lira’s steady decline has also spiked up Turkey’s current default swap (CDS) rate. This indicates a country’s level of risk for investors. Its five-year CDS is currently at the worst rate since 2008 making money harder to borrow at an affordable rate.

Soaring inflation

The inflation rate in Turkey is constantly rising. In May, it reached a peak of 73.5 percent, the highest since 1998. Reminiscent of Turkey’s economic crises in the 1990s, this inflation rate was a consequence of the lira’s depreciation and the increase in food and commodity prices.

However, despite this rise, Erdogan declared that inflation was on a downward trend, putting the blame on the global crisis. Adding that his government would “look for ways to reduce the cost-of-living burden”, he reiterated his commitment to his economic model. He believes that an anticipated boost to production will quickly cut the inflation rate.

Nebati, meanwhile, said that this model was helping manufacturing and exporting companies but not low-income people.

Following harsh criticism, he issued a correction, saying that current economic policies were aimed at promoting investment, production, exports, and employment in order to provide welfare for every part of the society, including low-income people.

However, production is inextricably tied to the import of goods and commodities. Without having any significant natural gas or oil reserves of its own, Turkey must pay global energy and commodity prices in dollars at a time when its lira is at its weakest point.

Oil and natural gas are necessary for not only the country’s factories but also its farms, so as global prices rise this pushes up the price of even domestically-produced food products.

In May, TUIK said the average annual rise in food prices was 91.63 percent, and 107.62 percent for transportation. Indeed, a litre of diesel stood at 6.8 liras in June 2021 while it is currently at 27.89 liras - representing a 300 percent increase.

In line with soaring inflation, the price of construction materials has also doubled, leaving Turkey facing one of its worst property crises in the last few decades. According to a Turkish central bank report published this April house prices have doubled in a year and rents have also skyrocketed.

These dramatic price rises have deeply unsettled the Turkish people and in response, the government has introduced a new cheap loan scheme for first-time house buyers - a group facing some of the toughest challenges.

Also, the government said any increase in property rents until 1 July 2023 was restricted to 25 percent in an attempt to curb rent rises.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.