Off to Turkey: Iranians flee one troubled economy for another

TEHRAN and ISTANBUL – His parents begged him to stay, but soon 33-year-old Darush Mozafari will leave Iran for Turkey, possibly forever.

Over the past decade, the civil engineering graduate has worked a variety of jobs, saving up for an eventual move.

Iran’s recent economic crisis has sped up his plans: he’s submitted his letter of resignation at the construction company where he works.

To survive and to have a better life, we chose to migrate to Turkey,

- Ali, Iranian living in Ankara.

However, he’ll be leaving with much lighter pockets than he had hoped after the rial lost around two-thirds of its value against the dollar this year.

“Over one night, I lost half of it after the US president issued an ultimatum and then killed the nuclear deal,” Mozafari said, sitting at an immigration company to finalise paperwork for his visa.

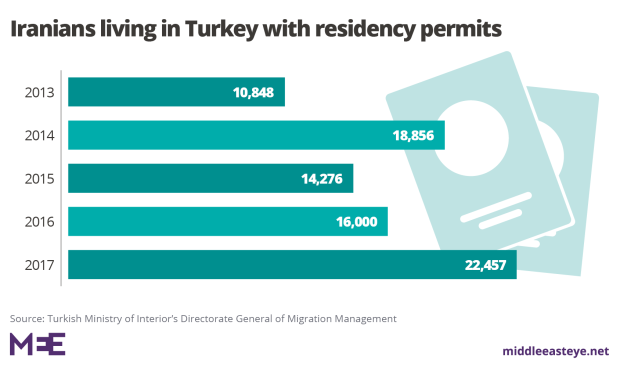

Darush is not the only one leaving Iran. Although official statistics haven’t been released, immigration advisors in the country say the numbers of Iranians who have decided to start a new life elsewhere has jumped significantly.

And for many, that next home is Turkey.

Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979 when nearly two million fled to Turkey, Iranians have tread a well-worn path to their neighbouring country for a variety of economic, religious and social reasons, particularly at times of political upheaval.

Many have come to study, start a new business or invest in property, saying they find better quality education and greater employment and investment opportunities.

And now the currency crisis in Iran has set off yet another wave, but this time those willing to make the move will be trading one troubled economy for another.

The value of the Turkish lira has plummeted by more than 40 percent since the start of the year amid concern over the country’s monetary policy and as a diplomatic row between Ankara and Washington has intensified.But this hasn’t put off Iranians. According to the Turkish Statistical Institute, TUIK, the number of properties bought by Iranians in Turkey jumped in the first six months of the year to 944 compared to 792 in all of 2017.

Their motivations include readily available loans from Turkish banks and a sense that their assets, which are currently losing value in Iran, will be in a safe place – or at least a safer place.

“To survive and to have a better life, we chose to migrate to Turkey,” said Ali, an Iranian living in Ankara.

“Iranian currency has lost its value, even against Turkey’s," he says. Still, the Turkish lira is more affordable for Iranians than the euro or the dollar.

"That’s why Iranian’s first step would always be Turkey, even when they actually want to migrate to Europe or America.”

Home sweet home?

Google "buying house in Turkey" in Persian and tens of pages will turn up, each suggesting a new way to buy a home or get a residency permit.

Reza Kami, chairman of the Iran-Turkey Chamber of Commerce, based in Tehran said Iranians have purchased around 1,000 homes and apartments in Turkey since the spring. Most are worth between $50,000 and $200,000, and the purchaser is automatically qualified for a residency permit.

Despite this, many of the purchases are most likely purely for investment, Kami said."Besides easy regulations and no need to get visas, people's predictions about their assets losing their value have played a key role in their decisions,” he said.

Mohsen Azarnejad, a consultant at a private emigration company, disagrees: for most Iranians buying property in the country, Turkey is home sweet home.

"People are mostly going to Turkey in order to live there,” Arzanejad said. “This wave has been intensified during the past four months."

Istanbul, and the resort towns of Antalya and Alanya are the three main cities that Iranians prefer, he said.

"People are going to Turkey for both life and emigration. But I don’t personally advise anyone to sell everything he has in Iran and go to Turkey to live,” he said. “That is an unpredictable future and it is too risky.”

‘I feel free here’

But for many Iranians, moving to Turkey has been about more about prospects for education and employment than cold hard investment.

An Iranian who has been in Turkey for eight years and works in the Association for Solidarity with Asylum Seekers and Migrants (ASAM), one of the biggest organisations helping immigrants in Turkey, told MEE that in the past six months, the number of Iranian migrants who have come to ASAM for guidance has increased by 25 percent. He spoke on condition of anonymity because he is not authorised to give interviews.

Some are coming with saved money and will try to find work or start a business.

The quality of education is not good in Iran, and also it’s not a perfect place for youth. There is social pressure, religious pressure. I feel free here in Turkey

- Ali, Iranian living in Turkey

“If they can earn more and settle down, they call their relatives or friends who are jobless or cannot earn enough in Iran. Some of them open new businesses in Turkey, partnering with a Turkish citizen, which makes the paperwork and official process much easier,” he said.

Others will be students whose parents can afford to send them to study in Turkey, who may later seek asylum in Europe, the US and Canada after graduation because “it’s easier to go to the West from Turkey than it is in Iran,” he said.

Seven years ago, Ali was one of these students. Originally from Tehran, Ali came to study and now works for a foundation run by a government ministry. Ali is an Azeri Turk, a Turkish-speaking ethnic group mostly concentrated in northwest Iran, along the Turkish, Armenian and Azerbaijan borders, and estimated to make up one-fourth of Iran’s population.

“Some of them say they are facing discrimination,” he said. “But in Tehran, I never experienced such discrimination.”

Studying abroad was always Ali’s dream, following in the footsteps of cousins and friends. “The quality of education is not good in Iran, and also it’s not a perfect place for youth. There is social pressure, religious pressure. I feel free here in Turkey,” he said.

“They could save some money for me out of concerns for my future. We didn’t know if I could find a job after graduation, because there are so many jobless people in Iran. There are people around us who can’t find a job for many years,” he said.

“My father bought my ticket to Ankara and put some money in my pocket.”

Under an agreement between Turkey and Iran, citizens of both countries can travel to the other country without a visa and stay for 90 days as tourists.

“In these 90 days, I could easily adapt because I know Turkish. I took the university entrance exam and later started my education in Ankara University, in the department of history. I graduated in 2015,” he said.

Ali said he wasn’t sure if he would stay after university when he first arrived. But as the years have rolled by, and particularly as the economic crisis unfolds in Iran, he said he is going to stay right where he is.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.