Turkey’s relocation of Syrian refugees threatens to split families apart

Rain fell hard on Istanbul on Saturday, leaving streets in this city of 15 million inhabitants nearly deserted.

As flash floods burst through neighbourhoods with large communities of Syrian refugees, Hussein* couldn’t help but see it as a sign that even Istanbul's weather had turned political.

“It’s like the new policy towards us refugees, maybe even a part of it. It’s here to wash us away,” joked the tall, thin Syrian man.

The policy he’s talking about is a deadline on Tuesday for unregistered Syrian refugees to leave Istanbul.

Last month, Turkish authorities announced plans to relocate unregistered Syrians living in Istanbul to cities where they are registered. Since then, more than 5,000 Syrian refugees have been detained yet rights groups say some have been deported to Idlib, Syria.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

By Tuesday, Hussein - like many others - will have to leave the city, leaving behind his eight-month pregnant wife, who is registered in Istanbul, and his two-year-old son who is not registered at all.

For many Syrians, this marks an abrupt reversal of what had until then been seen as welcoming Turkish policies for refugees - leaving them disoriented and fearful of the possibility of further backlash.

Living in fear

The forced relocations within Turkey are causing huge stress for many Syrians, affecting the progress they had made building new lives in the country and threatening to split families apart.

Unlike in many other countries, Syrian refugees were mostly free to choose where they wanted to live when they first arrived in Turkey.

'I left so much behind in Syria, now I’ll have to do the same in Istanbul'

- Hussein, Syrian refugee

They could apply for "temporary protected status" with their Syrian passports and reside in their chosen city of registration. In order to travel or live in another city, official policy dictated that Syrians should apply for authorisation to do so; but in practice, many were allowed to move freely without inspection.

Hussein fled Syria in 2015 and he registered and settled in Hatay, a Turkish province bordering Syria.

He came to Turkey’s economic and cultural capital in 2016 seeking better employment and became one of thousands of Syrians living in the metropolis despite being registered elsewhere in the country.

“I was a waiter in Hatay but I’m a qualified Arabic teacher. There were no teaching jobs for me there so I came here,” he explained.

Once in Istanbul, Hussein quickly found work in a private school and was happily building his career. It was there that he met the woman who would become his wife: Aisha*, a fellow Syrian from the city of Hama.

Hussein was introduced to Aisha through her relatives and soon afterwards the two were married and started a family.

“I had a good life here,” he said. “In Hatay, I was living in a small flat with five other people. Here we have our own flat.”

But since the crackdown was announced, Hussein has been living in fear of the increasing ID checks. Like many other Syrians he knows, he avoids leaving the house unless it is absolutely necessary.

Hussein has no idea where he will live or how he will earn money back in Hatay. Now 37 years old, four years after fleeing to Turkey, he is distraught at finding himself back at square one. “I left so much behind in Syria, now I’ll have to do the same in Istanbul.”

He is worried about leaving Aisha behind, particularly so close to her due date while the risk of random police raids is particularly high in the immediate aftermath of the deadline.

With Aisha being out of work as she prepares to care for two young children, the family will be without income until Hussein figures things out in Hatay.

While Aisha will have the emotional support of relatives who are registered in Istanbul during and after childbirth, Hussein is equivocal when speaking of how his forced departure will impact his family.

"If I'll be okay, she will be okay," he answers when asked about his wife’s fate; but whether Hussein will be okay remains unclear.

Hussein is not alone in his quandary. Wael Adeeb is a Syrian businessman living in Istanbul who voluntarily provides advice and assistance to those affected by the relocation policy.

“I know one family where half the members are registered in Izmit and the other half in Ankara but they are living, for the time being, together in Istanbul,” he told Middle East Eye. “They don’t know what to do. None of the older siblings could find work in Ankara and there is nothing in Izmit. The father is sick and needs surgery.”

‘End of hospitality’

Turkey is home to 3.5 million Syrian refugees. 550,000 are officially registered in Istanbul.

In the run-up to Istanbul mayoral elections in March and June, both the ruling and opposition party candidates used rhetoric critical of the refugee community. In recent months, anti-Syrian refugee sentiment and tensions have been growing.

Last month, several shops with Arabic signs in the Kucukcekmece district were vandalised and riot police had to disperse a crowd angry over claims that a Syrian boy had harassed a Turkish girl.

After losing both the initial election in March and a re-run in June in Turkey’s biggest city, the ruling AK Party has been looking for something to blame the loss on, according to Muzaffer Senel, a lecturer in Politics and International Relations at Istanbul Sehir University.

“They want to show they lost Istanbul due to refugees,” Senel told MEE. “Unfortunately, the government made a decision based on the rise of xenophobia and far-right nationalism in Turkey. This is the end of the government’s hospitality towards Syrians”.

For Hussein, the sudden toughening of Turkey’s stance on Syrian refugees is something he wishes the government had made clear earlier.

“I tried to change my ID registration when I moved to Istanbul, but when I went to the Directorate General of Migration Management, they told me I didn’t need to do anything. I tried multiple times and got the same response,” he explained. “Now they want me to move because I’m not registered.”

Adeeb said this is a common problem.

“The government was looking the other way, not checking whether Syrians were registered or had work permits. So people thought being unregistered was fine,” he explained.

“Now people don’t know what to do. People started businesses and employed other people based on the understanding that Syrians were exempt from the need for official documentation. There are people who have invested money in this country through their businesses and housing.”

Despite the disruption it’s causing for people like Hussein, Adeeb empathises with the government’s need to do something about the growing numbers of refugees in an overcrowded city with rising tensions.

However, he said, “the issue with the 20 August deadline wasn’t planned”.

'The government was looking the other way, not checking whether Syrians were registered or had work permits. So people thought being unregistered was fine'

- Wael Adeeb, Syrian businessman

Adeeb thinks a longer deadline should have been granted in order to create a database of unregistered refugees. In the run-up to that deadline, he argued, the Turkish government should have used funding it receives from the European Union to support unregistered refugees settling in new cities.

Instead, he said, “you have 17- and 18-year-olds being deported to Idlib overnight where al-Qaeda is waiting for them and pregnant women, due any day, being dumped alone at the other end of the country”.

The Turkish government has denied returning anyone to Syria. Speaking to Middle East Eye by phone, an employee at the Interior Ministry said: “Turkey is not deporting any Syrians. We are sending people to provinces where they are registered.”

Pendulum swing

Senel believes the lack of planning is down to political survival. “I think there will be a general election as early as March 2020. To strengthen chances of re-election, the AK Party wants to have all Syrians moved into this 'safe zone' they are trying to create in northern Syria.”

Joshua Landis, the director of the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma, thinks the sudden redistribution of Syrian refugees is a sign of a larger forthcoming political transformation.

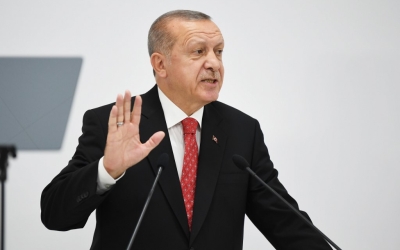

Welcoming these refugees, he says, was part of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Pan-Islamic vision

“It’s amazing that Turkey has been so hospitable to so many Syrians for so long. Few other countries would have been able to do that,” Landis told MEE. “I think most of that is down to Erdogan’s ideological commitment. But now there is bound to be a pendulum swing.

“Erdogan has been riding a wave of Eurasianism and Pan-Islamism. This has given Turkey a great boost, but ultimately we live in a world of nation states where borders are important.”

Staying on the right side of those borders is what Turkey’s unregistered Syrians are trying to do, but hope is fading fast.

Hussein runs his fingers along the dark folds under his eyes as he gazes at passersby running below to escape the downpour.

Once again, he jokes:

"You'd think these people were running from bombs," he says, before the smile fades from his lips as he is reminded of the uncertainty that lies ahead for him and his family.

"No one should ever have to run from bombs. May this country be spared such a fate."

*Names have been changed.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.