Cop28 deal to 'transition away' from fossil fuels a 'death warrant', campaigners say

The Cop28 climate summit in Dubai on Tuesday approved what supporters say is a "landmark agreement" to "transition away" from fossil fuels.

But while many are celebrating the historic inclusion of the term "fossil fuels" in the final text as "an unmistakeable signal" of the end of fossil fuels, campaigners say the final text is "marred by lack of finance and loopholes" and omits references to a “phase-out" or "phase-down", instead referring to the need to "transition away" from fossil fuels.

The final text is intended to identify gaps in climate initiatives since the 2015 Paris Agreement and outline a roadmap for future climate action.

While earlier drafts listed options for countries to phase out fossil fuels, the final text drops the term entirely.

A penultimate draft released on Monday drew fierce criticism from delegates and climate campaigners for removing the term and suggesting that countries “could” “reduce both consumption and production of fossil fuels".

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

After many countries rejected the draft, the negotiations ran into the early hours of the morning on 13 December, the final day of the summit.

While the final resolution attempted to strengthen the softened language, campaigners say the text is still watered down.

The final wording replaced the term "reduce" with "transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems", but stopped short of referring to a "phase out".

The term "could" is replaced by "calls on", something that critics have said is an "invitation… the *weakest* of all the various terms used for such exhortations," Leo Hickman, editor of Carbon Brief, said on X.

Campaigners have highlighted that the resolution is also riddled with loopholes allowing the fossil fuel industry "escape routes" through unproven technologies like carbon capture.

The text alludes to the need to “accelerate abatement and removal technologies" such as "carbon capture utilisation and storage" and recognises the role of "transitional fuels" in the energy transition away from fossil fuels.

Campaigners have warned this will legitimise these unproven technologies, which climate scientists say will not curb global heating, and hand countries a “licence to pollute”.

“It gives a free pass to the fossil fuel industry,” Harjeet Singh, director of the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative, told MEE.

While Saudi Arabia and its allies have opposed any reference to reducing the production and consumption of fossil fuels, many developed countries, including the US, have pushed for a phase-out of fossil fuels with "unabated" caveats.

'We have made an incremental stepchange over business as usual, when what we needed was a transformational change'

– Alliance of Small Island States

"It's a total disaster," Tard Foundation and Rise Up Movement activist Eriga Reagan Elijah told MEE. "1.5 [degree] C hangs in the balance, which makes the text a death warrant."

Meanwhile, Asad Rehman, the director of War on Want, said: "This outcome isn't the clarion call that was needed to prevent climate catastrophe. It’s not the clear signal to end the era of deadly fossil fuels.

"It still leaves us with our planet on fire, the poor left behind, and fossil fuel CEOs rubbing their hands with glee," he told MEE.

Samoa, on behalf of the chair of the Alliance of Small Island States, said that the resolution was passed without them being present in the room, adding that: "This process has failed us."

“We have made an incremental step-change over business as usual, when what we needed was a transformational change," they said.

'Dominated by polluters'

The climate talks have seen a fierce battle over the wording of the final agreement, with a “phase-out” or “phase down” of fossil fuels emerging as the biggest flashpoint.

While the terms lack definition, a “phasing out” means a radical shift away from coal, oil and gas until their use is eliminated, while “phasing down” means a reduction in use.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has said that a phasing out of fossil fuels is the only way to limit global heating to 1.5C.

Cop28 president Sultan al-Jaber came under fire for claiming that there is “no science” behind this target, although he later said the statement had been “misinterpreted”.

On 8 December, a leaked letter from the head of the Opec oil cartel - which represents the interests of petrostates including Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Venezuela - warned its member states that “fossil fuels phase-out” remains on the Cop negotiating table, and that they should “proactively reject any text or formula that targets energy, i.e. fossil fuels, rather than emissions”.

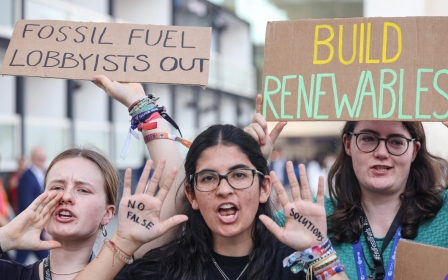

Campaigners say the watered-down commitments in the final text are riddled with the influence of fossil fuel and carbon capture lobbyists, who were present at the conference on an unprecedented scale: 2,456 industry-affiliated lobbyists were registered at the climate summit, almost four times the number at Cop27.

Meanwhile, the Guardian revealed that carbon capture lobbyists outnumbered indigenous representatives by 50 percent.

“Cop has been made and dominated by polluters," Elijah told MEE, “so we expected negotiations to be in favour of polluters."

'A poisoned chalice'

When it comes to climate finance, the debt owed by historic polluters to developing countries, the wording of the final resolution is similarly vague and lacks stringent obligations for rich countries to pay.

The agreement "acknowledges" the obligation of developed countries in leading climate finance and says that there must be “a progression beyond previous efforts".

But the final text also details the role of the private sector in plugging finance gaps.

"It's a poisoned chalice for developing countries, who will be required to underwrite the profits of capital markets, deepening the debt crisis, and ensuring an unjust and unequal transition," Rehman told MEE.

“Although Cop28 recognised the immense financial shortfall in tackling climate impacts, the final outcomes fall disappointingly short of compelling wealthy nations to fulfil their financial responsibilities - obligations amounting to hundreds of billions, which remain unfulfilled," Singh told MEE.

“There's just one reference to a just transition and [they are] not even saying that we are willing to support countries in making that transition,” Singh said, referring to a set of principles for a just and equitable energy transition.

“So developing countries are largely left on their own.”

The new text also acknowledges the efforts of developed countries in meeting the $100bn a year climate finance goal agreed in 2009. While the resolution put the figure at $89.6bn in 2021, a 2023 Oxfam report found that donors’ contributions were likely much lower than reported.

'Developing countries are largely left on their own'

– Harjeet Singh, Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative

Climate finance requires a minimum of $2.4 trillion of investment and transfers of technology for climate adaptation and mitigation by 2030.

Furthermore, money pledged for climate finance often comes in the form of loans, adding to the debt burdens of already indebted countries.

“If you owe me $100, you are supposed to pay me. Instead, you give me a $10 loan with conditionalities to control how I use my money,” said Fadhel Kaboub, a senior adviser with Power Shift Africa.

"You give me another $10 in exchange for having control over my forests (aka carbon markets). You invest another $10 in green electricity that I must export to you on favourable terms. You outsource another $10 worth of low value-added manufacturing to produce cheap consumer goods for you. None of this should count as climate finance."

A dearth of climate financing has deterred some developing countries from joining the calls to phase out fossil fuels.

"Africa is not solidly behind fossil fuel phase-out, but the reason is very different [to that of petrostates],” Singh told MEE.

He added that developing countries would not be able to finance a transition from fossil fuels without funding from rich countries.

"For [developing countries], it's more conditional: If [rich countries] put money on the table and say keep [fossil fuels] in the ground, they will accept. So if [rich countries] don't provide money and [developing countries] have to fund the energy transition, how are they going to fund it?” Singh said.

Climate campaigners have also highlighted the "hypocrisy" of developed nations like the UK, US and Australia for criticising countries for not supporting a “phase-out” of fossil fuels, while continuing domestic oil and gas development.

“How do you deal with that hypocrisy?” Singh said. “How can the US make a stand [on the phasing out of fossil fuels] when back home they’re leading oil and gas expansion between now and 2050?”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.