'Unimaginable despair': Khaled Hosseini's tribute to Syrian boy Alan Kurdi

The world is a different place to the one left by Alan Kurdi.

Though the three-year-old Syrian refugee never saw it, his death in the Aegean Sea three years ago last Sunday changed public discourse and opened people’s eyes to the trauma of refugees and the Syrian war.

Khaled Hosseini, the multiple award-winning author of The Kite Runner and goodwill ambassador of UNHCR, the United Nations’ refugee agency, hopes Kurdi’s example can still do the same.

The novelist describes his latest work, Sea Prayer, as a tribute to the young boy who fled north Syria’s Kobane amid the civil war and Islamic State group insurgency only to find danger far from home.

I kept trying to fathom the anguish that his father had to endure each time he saw photos of his son lying dead on that beach in Turkey

- Khaled Hosseini

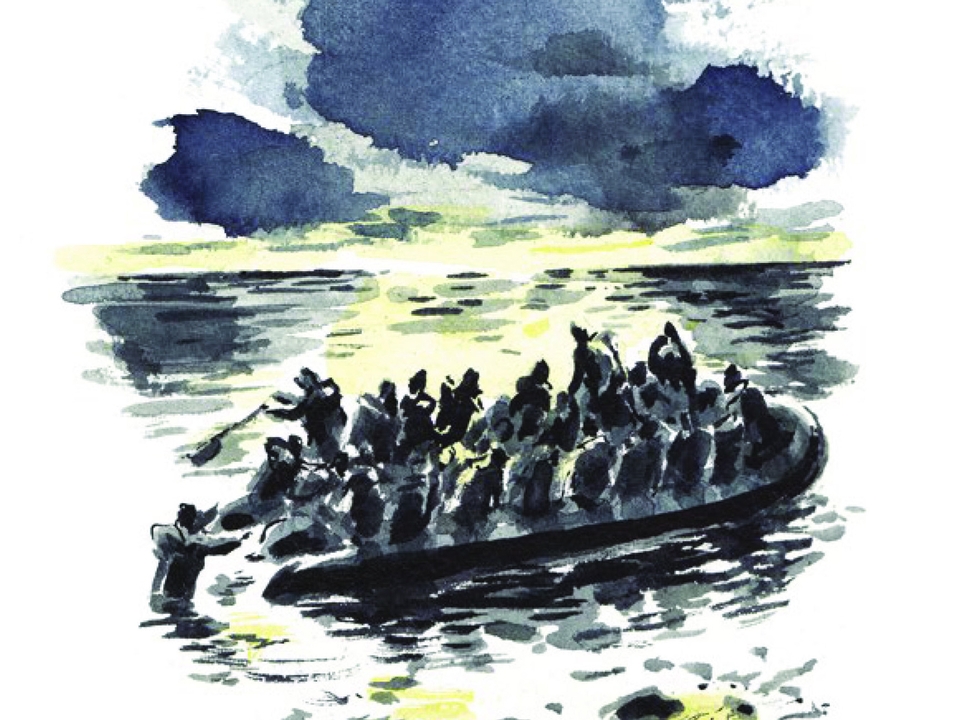

A slim volume of words scattered across the pages in fragments, Sea Prayer is a father’s reminiscence of a Syria lost forever, and an anticipation of a treacherous journey across the water to a future far from bombing, starvation and death.

It tells of a father’s choice – or lack of one – as conflict drives him to take his family from one danger to another in search of peace and safety.

This relationship between father and son is what struck Hosseini three years ago, and drove him to write Sea Prayer in memory of Kurdi and his family.

“I have two children of my own,” Hosseini says. “When I saw the photo of Alan Kurdi’s body on the beach, I felt gutted.

“I kept trying to fathom the anguish that his father had to endure each time he saw photos of his son lying dead on that beach in Turkey, or of a stranger lifting his child’s body from the water, a stranger who knew nothing about Alan, his favourite games, his laughter, or his favourite food.”

Presidents and prime ministers were moved to comment, and shift their policies to better reflect a public opinion that found new empathy for the hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants crossing the Mediterranean.

“Alan Kurdi’s death, the manner of it, pricked the conscience of millions around the world,” Hosseini says.

“We saw outpourings of solidarity and empathy. Countries opened borders. People everywhere gave to charities that support refugees.”

Today such an atmosphere feels foreign. Migrants and refugees are still attempting to cross the Mediterranean, and losing their lives on the way. But the attitude of Europe to the refugees has changed markedly.

This year alone 1,549 have died attempting to cross into Europe from Asia or North Africa by sea. “Some of the victims were children younger than Alan,” Hosseini notes.

But the anger, upset and horror has receded – partly, Hosseini says, due to a fatigue that accompanies statistics.

“It seems we can respond emotionally to a single tragedy that pierces our conscience, but paradoxically, when faced with larger scale suffering, we lose the emotional connection and our compassion seems to wane,” he says.

“This is why storytelling around this issue, while by no means enough on its own, remains vital.”

Sea Prayer seeks to tell this story and make people care once more.

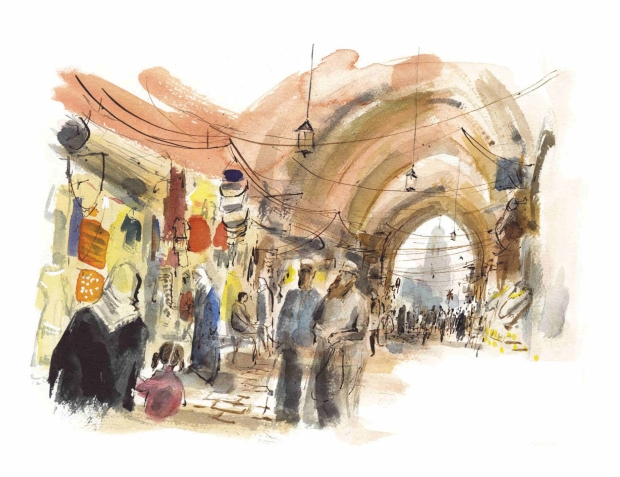

Its pages are full of swirling, evocative illustrations by Dan Williams.

Bucolic scenes of rural Syria and the humming souks of Homs bleed into images of war, and finally the dark green sea.

But storytelling isn’t enough, he admits. “Ultimately, we need policy changes that provide better protection for refugees, better access to asylum in EU member states, more adequate reception centres, and more access to safe and legal ways to enter Europe.”

Unfortunately, policy in the West seems to be headed only one way. Many voters and politicians now see refugees as a problem.

'For a meaningful shift to happen in our minds, we need to care first, and in order to care, we have to feel first'

- Khaled Hosseini

Sweden, a country that quickly opened its doors to Syrians refugees, has largely closed them again.

Migrants rescued from the Mediterranean are refused entry into countries and stranded at sea for days at a time.

Greece last week arrested a Syrian refugee who pulled a sinking ship to safety in 2015 on charges of people trafficking.

And on the island of Lesbos, conditions in Moira camp are so awful that children as young as 10 are attempting suicide.

Meanwhile anti-refugee rhetoric ramps up from the United States, to Germany, to Italy – married to a rise in far-right politics.

“The rise in anti-refugee sentiment that we are witnessing is of grave concern to me,” Hosseini says, conceding that it is a complicated problem.

But this tension can be bridged, he says, through a better understanding of who refugees are and why they are arriving on western shores in the first place.

“Any legitimate discussion of this issue has to start with this fundamental truth: that no one chooses to leave home, land, community, and risks their lives coming to Europe in rickety unseaworthy boats unless they were cornered into doing so by desperate circumstances far beyond their control,” he says.

It is an experience he has had first hand in his work with the UNHCR.

“The refugees I have met in the course of my travels, be it in Uganda or Afghanistan or Lebanon, have all inspired me enormously and enriched my life,” he says.

“They reminded me again of how what they hope for, more than anything else, is to return home and resume their former lives in peace.

“A Syrian refugee I met in Lebanon recently told me, ‘Even heaven is not home.’”

Khaled Hosseini will be donating all of his sale proceeds from his book to UNHCR.

Sea Prayer is out now.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.