US policy in Middle East: 10 defining moments from decade

A time for deals and a time for bombs. A time for diplomacy and a time for angry tweets. A time for aggression and a time for retreats.

This decade has been a wild ride for US foreign policy in the Middle East.

There were some whiplashes and U-turns between the presidencies of Barack Obama and Donald Trump. Global attitudes shifted. Some things remained the same.

What is certain is that after the election of Trump in 2016, US partisan politics have seeped into Washington's foreign policy like never before.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

To highlight those changes, Middle East Eye has revisited 10 moments that defined US policy in the Middle East over the past 10 years:

Bombing Libya

As a candidate, Obama made his opposition to the Iraq war a focal point of his 2008 successful presidential campaign. Still, the new decade showed that he was not opposed to the use of force.

On 19 March 2011, Obama authorised US troops to participate in a Nato-led global coalition against then Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi - continuing a trend of so-called humanitarian military interventions.

Still, the intervention in Libya was drastically different from George W Bush's wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. With no boots on the ground, the Obama administration emphasised cooperation with allied nations in a "leading from behind" approach that would define the White House's foreign policy over the next five years.

"For generations, the United States of America has played a unique role as an anchor of global security and as an advocate for human freedom," Obama said in a speech on 28 March.

He added that he was reluctant to "use force to solve the world’s many challenges".

"But when our interests and values are at stake, we have a responsibility to act. That’s what happened in Libya over the course of these last six weeks."

By the end of August of that year, Nato-backed rebels took control of the capital Tripoli, and in October they captured and summarily executed the Libyan leader.

More than eight years later, Libya is still struggling for stability with two governments and multiple armed groups vying for power.

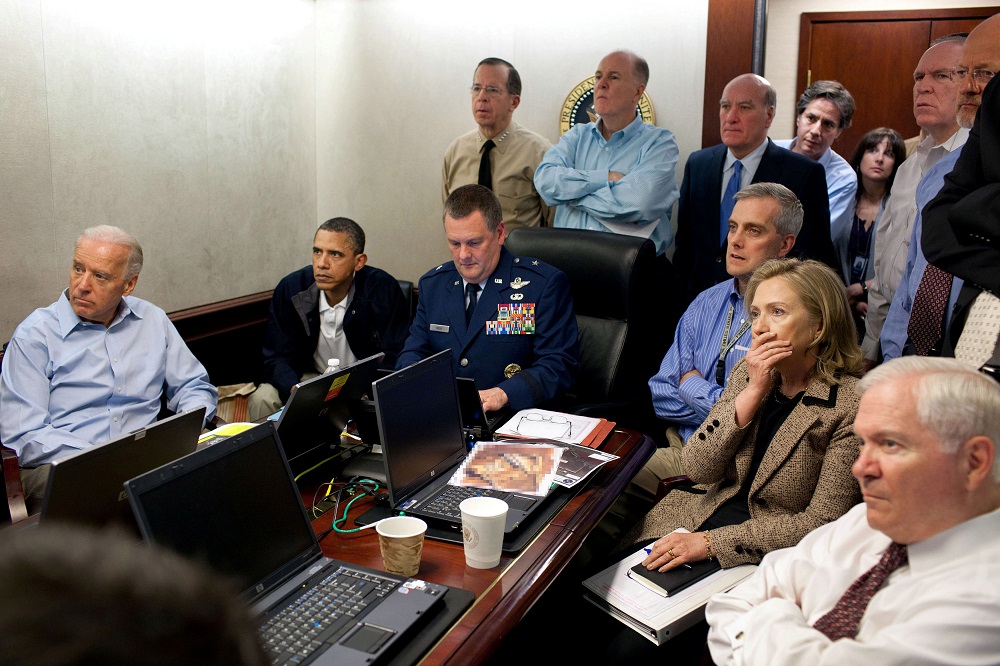

Killing Osama bin Laden

If America's policy towards the Middle East in the 2000s were defined by the 9/11 attacks, the killing of al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden marked the beginning of a new decade - militarily.

On 2 May 2011, American special forces gunned down the Saudi militant in a special operation in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

In many ways, the incident was symbolic of how the United States pursued the "war on terror" under Obama's leadership. Unlike Iraq's Saddam Hussein, who was captured after a costly invasion, bin Laden was targeted in a limited operation in a country that was not an active war zone for the United States.

"A small team of Americans carried out the operation with extraordinary courage and capability. No Americans were harmed," Obama said late on that evening.

"They took care to avoid civilian casualties. After a firefight, they killed Osama bin Laden and took custody of his body."

Civilian casualties from targeted killings and drone strikes in Obama's covert war against militants across the Middle East would become a major concern for rights groups across the world.

During his eight years in office, Obama authorised 540 drone strikes - mainly in Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan - killing hundreds of civilians.

Not enforcing Obama's 'red line' in Syria

At the start of the conflict in Syria, many hawkish voices in Washington called on the Obama administration to intervene militarily against the government of President Bashar al-Assad.

The 2011 Syrian uprising had shifted from largely peaceful protests to an all-out armed rebellion after hundreds of demonstrators were fatally shot across the country.

Wary of the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as well as the instability in Libya, Obama made it clear that Washington had no plans for a military intervention in Syria. Unless...

"We have been very clear to the Assad regime, but also to other players on the ground, that a red line for us is we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilised," Obama said at a news conference in August 2012. "That would change my calculus."

Almost exactly a year later, on 21 August 2013, a chemical weapons attack killed hundreds of Syrians in rebel-held Ghouta outside Damascus.

Washington blamed the attack on the Syrian government. Obama's red line was crossed.

Instead of mobilising for military action, the US chose diplomacy, brokering a deal with Russia that saw the Syrian government agree to give up its chemical weapons.

Obama's refusal to retaliate militarily against the Syrian government was seen as a turning point in the war, as it cemented the perception that America would not intervene directly.

In 2017 and 2018, the Syrian government was again accused of using chemical weapons in Khan Sheikhoun and Douma respectively. Both attacks led to limited military responses by the Trump administration.

Backing Saudi Arabia's war in Yemen

The war in Yemen has caused the world's worst humanitarian crisis, and the United States has been an active participant in it.

Shortly after Saudi Arabia led a coalition of neighbouring nations on a bombing campaign in Yemen against the country's Houthi rebels, then US President Obama announced that Washington would provide logistical support to Riyadh.

"In support of GCC actions to defend against Houthi violence, President Obama has authorised the provision of logistical and intelligence support to GCC-led military operations," the National Security Council said in a statement on 25 March 2015.

"While US forces are not taking direct military action in Yemen in support of this effort, we are establishing a Joint Planning Cell with Saudi Arabia to coordinate US military and intelligence support."

A few years later, legislators from Obama's own Democratic Party would lead efforts to end US assistance to the Saudi-led coalition. In April, Trump vetoed a congressional resolution ordering the administration to halt support to the Saudi-led coalition.

As the conflict approaches its fifth anniversary, the war remains at a stalemate with the Houthis in firm control of the capital Sanaa.

The war has brought the already impoverished country to the verge of famine, killed thousands of people and caused outbreaks of preventable diseases, including cholera.

The Iran deal

After decades of animosity and distrust, Washington and Tehran seemed to resolve one of the major points of contention between the two countries - Iran's nuclear programme.

The United States and Iran - along with other major world powers - signed an agreement that would see the Islamic Republic significantly scale back its nuclear programme in exchange for the lifting of sanctions against its economy.

Representatives of the international community announced the deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, from Geneva on 14 July 2015.

Obama later hailed the accord as a "very good deal" that achieves one of Washington's "most critical security objectives", despite failing to address broader disagreements with Tehran.

War was the only alternative to diplomacy with Iran, Obama said in a lengthy speech defending the agreement in August 2015. "The only certainty in war is human suffering, uncertain costs, unintended consequences."

Allowing UN resolution against Israeli settlements

On his way out of the White House, Obama refused to veto a UN Security Council resolution condemning illegal Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem.

The resolution, adopted on 23 December 2016 with 14 votes in favour and America abstaining, denounced the establishment of settlements and decried them as a "flagrant violation under international law".

For the previous eight years, the White House had openly criticised Israel's settlement activity. Still, in 2011 the US administration vetoed a similar resolution in the Security Council to protect Israel.

White House officials justified withholding the UN veto in 2016 by stressing that Washington had exhausted all efforts to advance peace between Israelis and Palestinians through direct negotiations.

"We could not in good conscience veto a resolution that expressed concerns about the very trends that are eroding the foundation for a two-state solution," White House aide Ben Rhodes said at the time.

Recognising Jerusalem as capital of Israel

No American president has ever strayed from Washington's commitment to Israel's security. From Harry Truman to Barack Obama, Republicans and Democrats in the White House have sided with Israel in its conflict with the Palestinians.

Trump took that support to another level, breaking international norms, reversing decades-long policies and defying some of Washington's closest allies to deliver successive favours to Israel's right-wing government.

Over three years in office, the Trump administration has appointed a hardline pro-settlers lawyer as ambassador to Israel, cut funding to the UN agency for Palestinian refugees (UNRWA), pulled the US from the UN Human Rights Council and declared that settlements are not necessarily illegal.

But perhaps the biggest policy shift was moving the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem and recognising the holy city as the capital of Israel.

"Today we finally acknowledge the obvious - that Jerusalem is Israel's capital. This is nothing more or less than a recognition of reality. It is also the right thing to do," Trump said in a speech announcing the move on 6 December 2017.

Global outrage followed, with the UN General Assembly overwhelmingly denouncing the US administration's decision in a resolution backed by some of Washington's closest European allies.

While Trump said in his announcement that the move does not change the contested status of the holy city, he later gloated about taking Jerusalem "off the table", suggesting that he resolved the issue in favour of Israel.

Jerusalem is emblematic of the historical pain and betrayal inflicted on Arab people, James Zogby, president of the Arab American Institute, told MEE at the time.

"It's the wound that never heals, and this would simply put salt in the wound," he said.

Leaving the Iran deal

It took Trump 17 months to leave the deal that he repeatedly called the "worst ever". Top White House aides had previously recommended staying committed to the pact.

By 8 May 2018, when Trump announced leaving the agreement, he had acquired a new team of foreign policy advisers from the key officials he hired after assuming the presidency.

Gone was Rex Tillerson, who was sympathetic to the deal, replaced by the more hawkish Mike Pompeo at the State Department. And in a bad omen for diplomacy, Trump had appointed John Bolton as national security adviser.

Trump argued that the deal gave Iran too much without ending its nuclear programme, all while failing to address other issues with the Islamic Republic, including its support of militant groups.

"The deal lifted crippling economic sanctions on Iran in exchange for very weak limits on the regime’s nuclear activity - and no limits at all on its other malign behavior, including its sinister activities in Syria, Yemen and other places all around the world," he said in his announcement.

Before the end of 2018, the US would reimpose biting sanctions on various Iranian industries and individuals, intensifying tensions between the two countries and bringing them to the verge of military confrontation in the Gulf.

'Standing with Saudi Arabia' after Khashoggi murder

Six weeks after Saudi government agents killed and dismembered a US resident and Washington Post columnist in the kingdom's consulate in Turkey - a Nato member - the White House put out a news release headlined: "Statement from President Donald J. Trump on standing with Saudi Arabia".

"Representatives of Saudi Arabia say that Jamal Khashoggi was an 'enemy of the state' and a member of the Muslim Brotherhood," read the statement, released on 20 November 2018.

It was a clear indicator that Trump would act as Saudi Arabia's defender-in-chief amid the global fallout after Khashoggi's murder.

The statement went on to tout Saudi Arabia's arms purchases from US weapon manufacturers and berate Iran over regional conflicts.

"The United States intends to remain a steadfast partner of Saudi Arabia to ensure the interests of our country, Israel and all other partners in the region," Trump said.

Trump's active advocacy for the kingdom and its rulers after the murder would define his relationship with Saudi Arabia as he continues to fervently back Riyadh in other regional matters, including the war in Yemen and the confrontation with Iran.

Pulling US troops from northern Syria

After a phone conversation with Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan in early October, Trump announced that American troops would withdraw from northern Syria, effectively giving the green light for a Turkish military operation in the region.

"Turkey will soon be moving forward with its long-planned operation into Northern Syria," the White House said in a statement on 6 October. "The United States Armed Forces will not support or be involved in the operation, and United States forces, having defeated the ISIS territorial 'Caliphate,' will no longer be in the immediate area."

The decision caused an enormous backlash in Congress. The Turkish military aimed to clear US-backed Kurdish fighters, who played a major role in the fight against the Islamic State (IS) group, from northern Syria.

The US withdrawal was seen as betrayal to America's Kurdish allies. Congress introduced several measures to impose sanctions on Turkey over the incursion and reject Trump's decision.

Subsequently, both the House of Representatives and the Senate approved resolutions recognising the Armenian genocide in rebuke of Turkey.

For his part, Trump said he will keep a small group of US troops in Syria to protect oilfields in the northeast of the war-torn country.

"We're keeping the oil. We have the oil. The oil is secure. We left troops behind only for the oil," Trump said in November.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.