Gaza 2020: Has the Palestinian territory reached the point of no return?

In 2012, a United Nations report painted a bleak picture of the Gaza Strip and the conditions facing its Palestinian inhabitants.

Its economy was sluggish, its healthcare system beleaguered and its natural resources dwindling. But darker days were to come, the UN predicted.

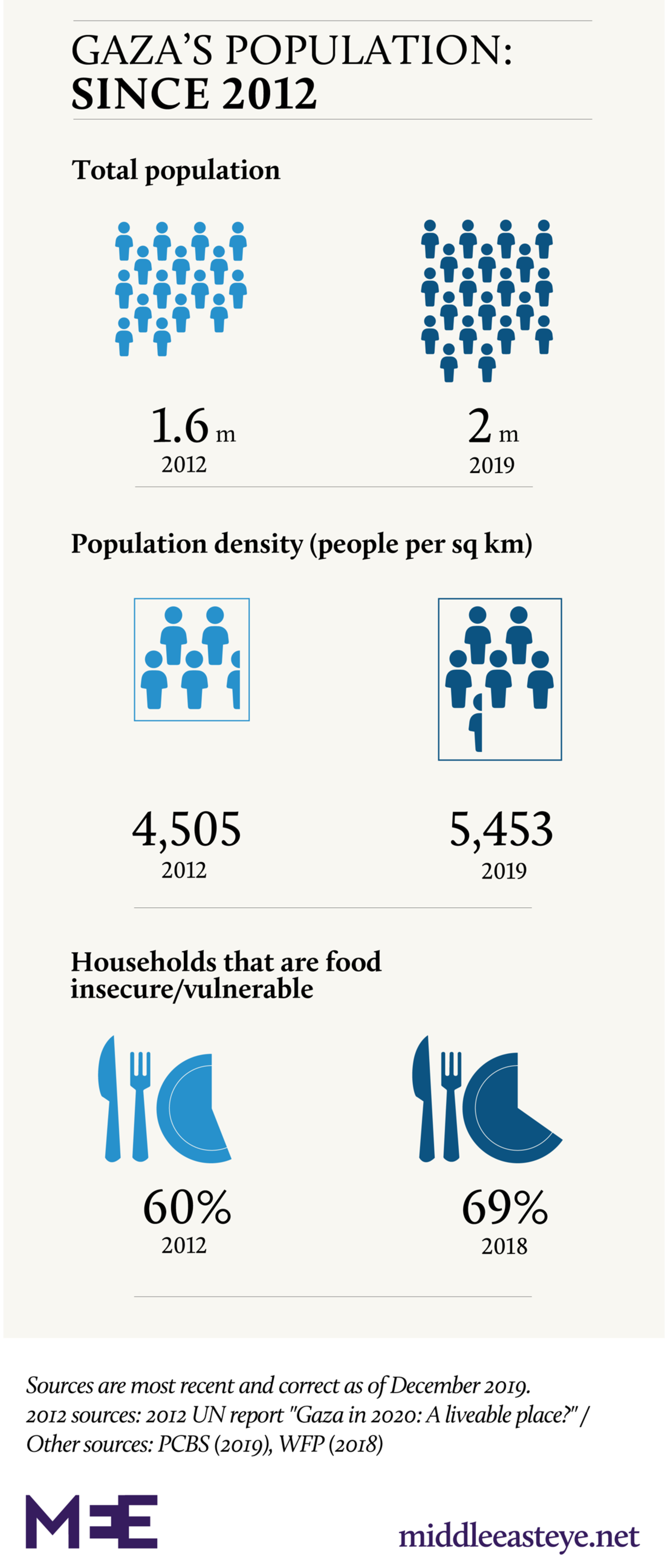

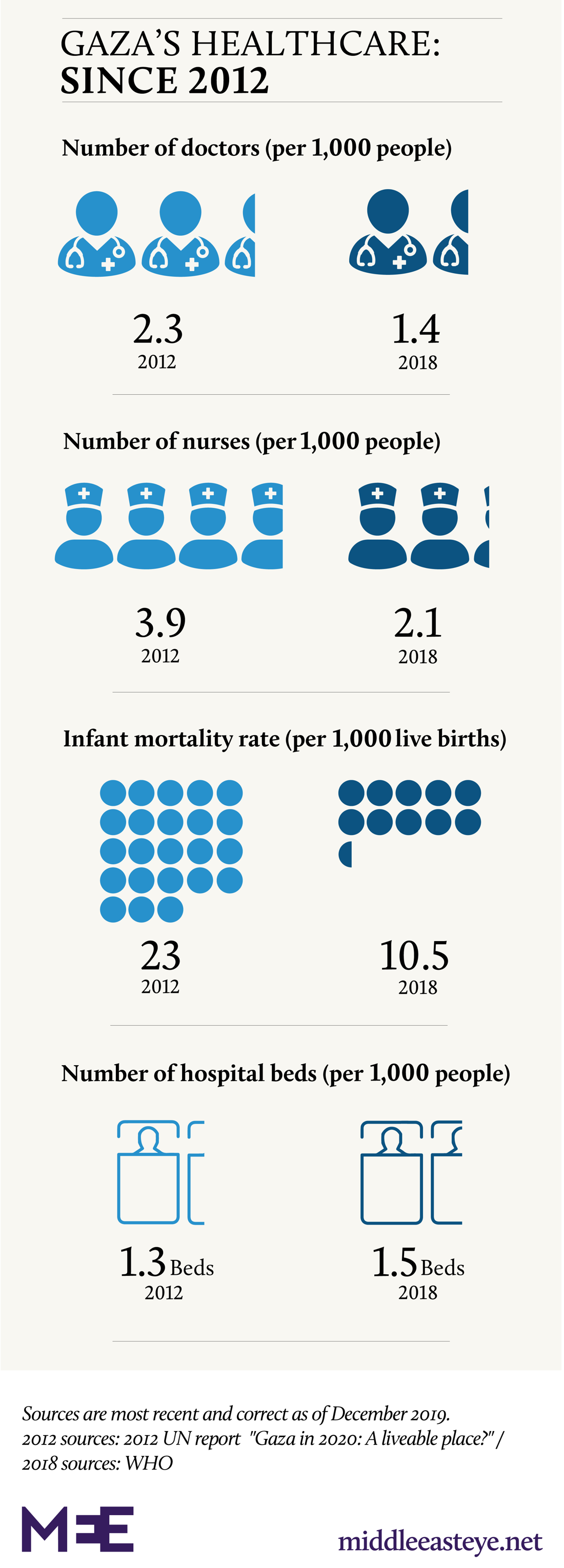

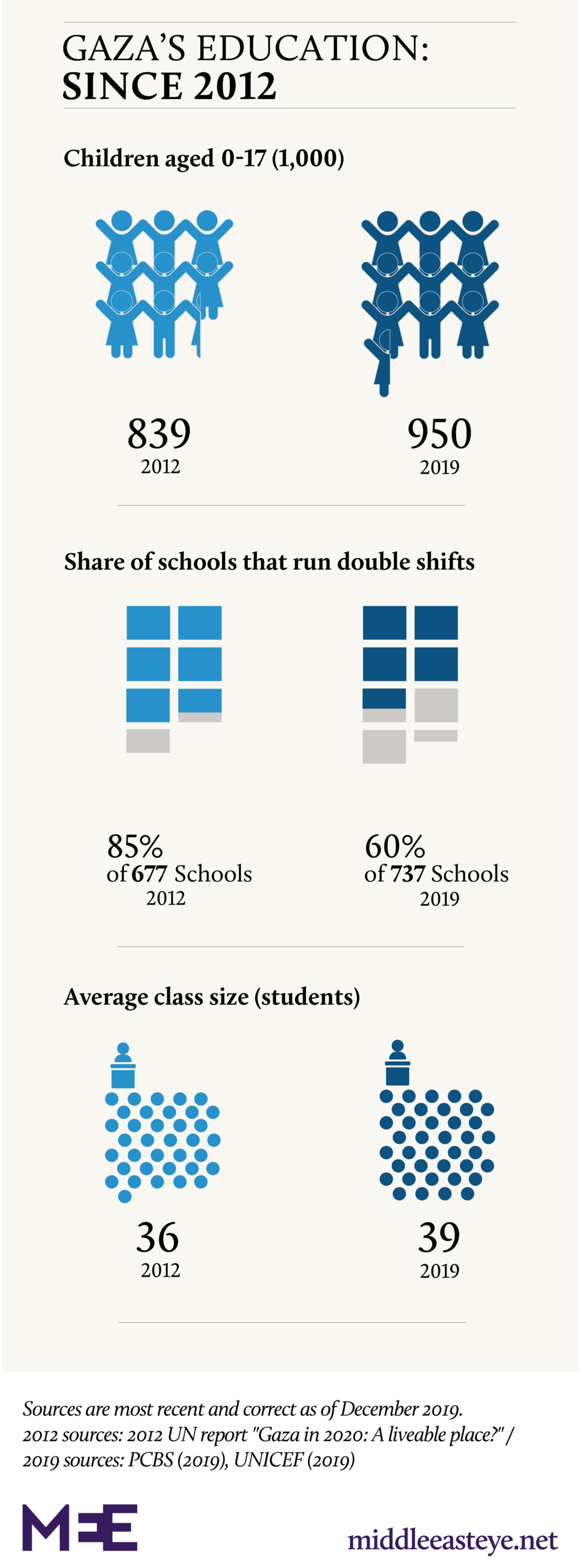

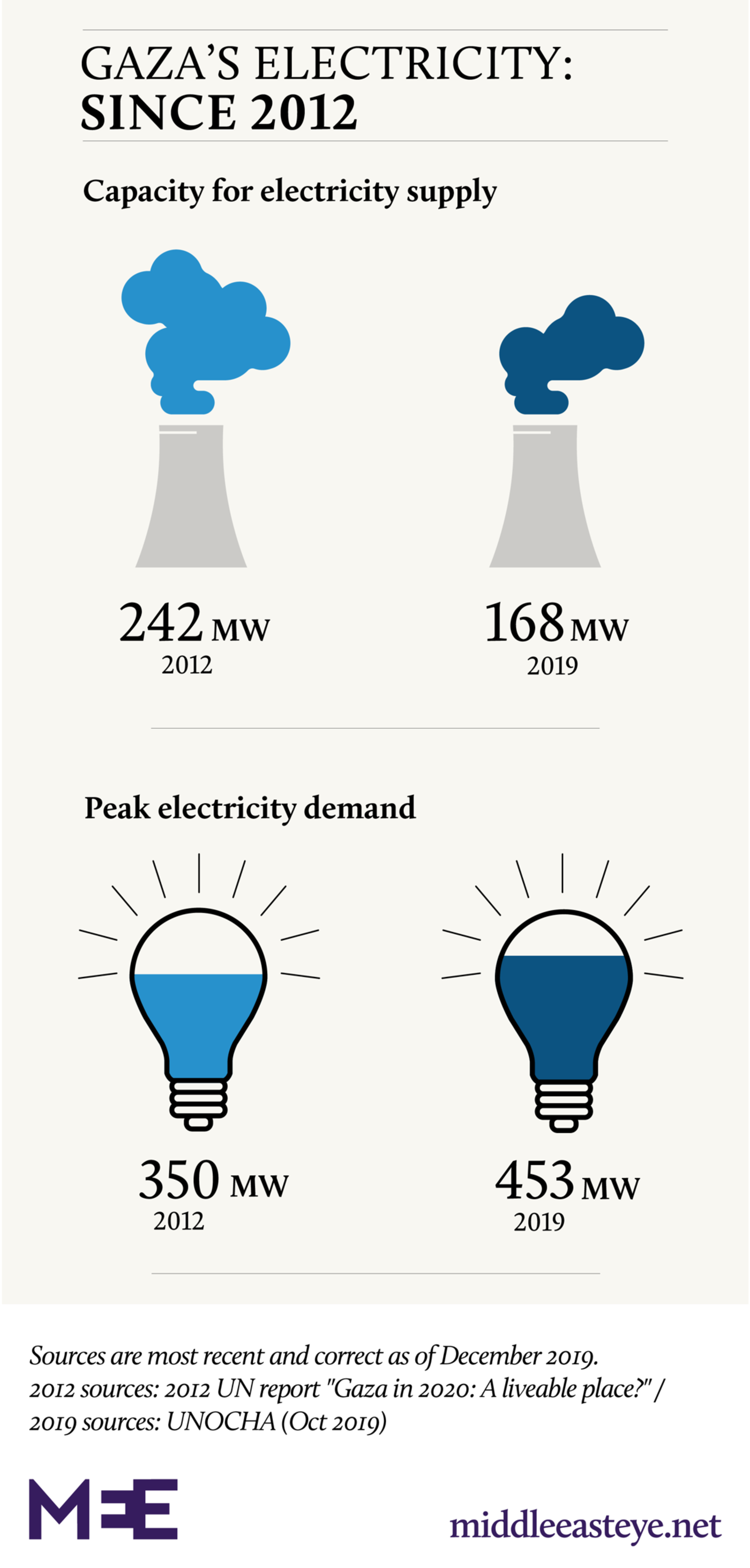

By 2020, Gaza’s population would surpass two million. Peak demand for electricity would soar by more than 50 percent, the report projected, and the territory's coastal aquifer could be damaged beyond repair. The UN called for a massive injection of resources, including thousands more doctors and nurses, a doubling of electricity capacity and at least 440 new schools.

It is now almost 2020. The UN's projections about Gaza's ballooning demands have proven largely accurate - but the delivery of essential services has failed to catch up.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Unemployment has reached nearly 50 percent, the per-person ratio of doctors and nurses has dropped, more than two-thirds of households are food insecure, and just three percent of Gaza's aquifer water is safe to drink, according to official statistics and aid agencies.

Michael Lynk, the UN's special rapporteur on human rights in the Palestinian territories, told MEE: "The prediction of unliveability has already arrived. The common measuring stick used by the UN or any other international organisation to be able to evaluate how people live is human dignity, and Gaza has been without human dignity for years now."

Surviving in Gaza

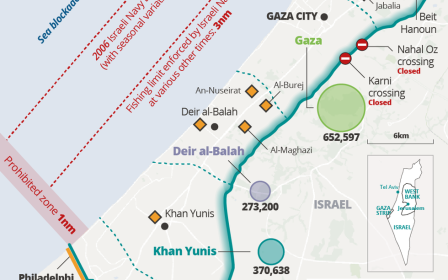

Since Hamas rose to power in Gaza in 2007, Israel has blockaded the coastal enclave, with severe restrictions on the movement of people and goods. Fuel shortages, power cuts, contaminated water and crumbling infrastructure have been compounded by repeated Israeli offensives. The most recent war, in the summer of 2014, killed more than 2,200 Palestinians and devastated tens of thousands of homes.

During the early years of the siege, Israel calculated the minimum number of calories that Palestinians in Gaza would need to survive (the information came to light following a successful legal fight by the Israeli NGO Gisha). These figures were then used to determine how much food aid should be trucked in, essentially keeping the territory on life support.

"It was going to keep Gaza hungry but not starving, and that continues to be ... the Israeli strategy towards this," Lynk said.

"As long as Gaza doesn't revolt; as long as there isn't another periodic pounding of Gaza, using among the most sophisticated armaments that the world has; as long as Gaza stays off headlines in the world, the world is not going to do very much to change this."

Haidar Eid, an associate professor at Al-Aqsa University in Gaza, described Israel's policy towards Palestinians in the enclave as "genocidal".

"They are a constant reminder of the original sin committed in 1948," Eid told MEE, referencing the Nakba, the mass expulsion of Palestinians that accompanied Israel's founding. "Israel wants to punish them for their resistance, for not being subservient subjects, and make them give up on their internationally guaranteed right of return."

Decline for Palestinians

Other observers have noted how, long before the 2020 deadline, the Israeli siege had already produced untenable conditions throughout Gaza. Restrictions on fishing zones - reduced to 10 nautical miles from 15 earlier this year - impede people's livelihoods. Import bans prevent critical goods, such as fuel and cooking gas, from entering the territory. And routine blackouts make daily life a struggle, with power sometimes available for just a few hours a day.

For some of the hardest-hit Palestinians, relief is impossible. This past September, Israel approved fewer than two-thirds of applications for patients to leave the territory for medical reasons. Some were interrogated as a prerequisite for permit approval - a practice denounced by human rights groups, such as Physicians for Human Rights, who point to Israel's history of coercing patients into becoming collaborators in exchange for needed hospital care.

The "de-development" of health services means that basic technology often isn't available in Gaza, while drugs and medical personnel are in short supply, noted Gerald Rockenschaub, head of the World Health Organization's office for the occupied Palestinian territories.

"It's not an abrupt decline; it's a chronic decline," he told MEE. "The system is always very close or on the brink of collapse."

International aid to the densely populated territory, while preventing a total shutdown, has created humanitarian dependence rather than fostering development in Gaza, experts note. At the same time, funding cuts this year by the Trump administration to UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestinian refugees, have deepened the crisis.

"There is a development abyss in the Gaza context," Jamie McGoldrick, the UN's humanitarian coordinator for the occupied Palestinian territories, told MEE, noting that it has been felt acutely in the health and education sectors.

Schools are running double - and even triple - shifts to accommodate the growing youth population. Meanwhile, hospitals have been stretched beyond their capacity, especially as the Great March of Return protests, which began in 2018, have resulted in thousands of injuries.

Yet, while humanitarian assistance is little more than a quick-fix solution, analysts say, weaning the territory off of this aid will be a complex and difficult process.

"You can't just say, 'OK, tomorrow no more food, no more support. You go elsewhere.' There is no 'elsewhere' in Gaza ... People are dependent on humanitarian [aid]," McGoldrick said.

"We have to switch that to something which is more sustainable, and certainly something much more dignified than what we have right now."

Palestinians: 'Alive for lack of death'

Kamel Hawwash, a British-Palestinian professor based at the University of Birmingham, told MEE that to the people of Gaza, the UN's 2020 prediction has long since come true. He said that many cite the Arabic saying: "We are alive for lack of death."

Israel's policy is one of containment, Hawwash said, and at the end of the day, "Israel wants to keep 'quiet' in Gaza. If Hamas provides it, then fine. If it doesn't, then [Israel] attacks the strip."

Israel has also reportedly been encouraging Palestinians to leave Gaza permanently, aiming to further reduce their presence on the ground. Earlier this year, a government source reportedly acknowledged that "attempts have been made" to persuade other nations to take them in, adding that Israel would assist with transportation.

For Gaza to emerge from its current predicament, Hawwash said, the intra-Palestinian rift between Fatah and Hamas must be mended and the Israeli siege must end, allowing stability to take root.

"Clearly, if the refugees who make up 80 percent of the population were to return to their homes - as they are entitled under international law - then Gaza could be liveable and prosper."

A successful political process could pave the way for a more development-oriented strategy in Gaza, McGoldrick said, potentially attracting new investments in water-supply systems, industrial zones and job creation.

He called the blockade "the biggest inhibitor to development" while acknowledging that the 2020 deadline of unliveability was in itself "an artificial creation" of the UN.

"That doesn't mean anything to any Palestinian ... People are just trying to get through the day, surviving day by day," he said.

Yet, with the continuing population growth, service reduction and soaring unemployment, Gaza may be approaching a point of no return.

Sara Roy, a senior research scholar at Harvard University's Center for Middle Eastern Studies, told MEE: "The term 'unliveable' … is meant as an alarm bell for the international community, but that bell has been ringing for a long time."

The warning, she said, has been ignored amid international indifference and humanitarian interventions that merely serve as a substitute for human rights.

"Without the unencumbered movement of people and goods," Roy said, "Gaza will be condemned to continued ruination."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.