![Malcolm's ideas especially resonated with young people - in both America and abroad [Azad Essa/MEE]](/sites/default/files/styles/max_2600x2600/public/images-story/mural_malcolm-colour_0.jpeg?itok=ft2WVU5a)

The fraught and unforgettable: How Malcolm X's legacy lives on in America

It’s a cold Thursday afternoon in New York City. A tall Black man, in a black jacket, black track pants and black sneakers enters the Malcolm Shabazz Mosque on 116th Street in Harlem. He looks around before approaching the older man hunched over the reception desk.

“Is this the Malcolm X Masjid, brother ... can I make salah, here?” he asks softly, removing the black hoodie from over his head.

“You sure can, just sign the register,” the man behind the counter says, pointing at a handwritten directory and then at the narrow passage adjacent to him. “Go that way. Are you from out of town?”

“I am from South Carolina.” the young man says.

“My name is Malcolm,” he says with a smile, before disappearing to perform the late afternoon prayers.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

'We couldn't see him, but we could hear him'

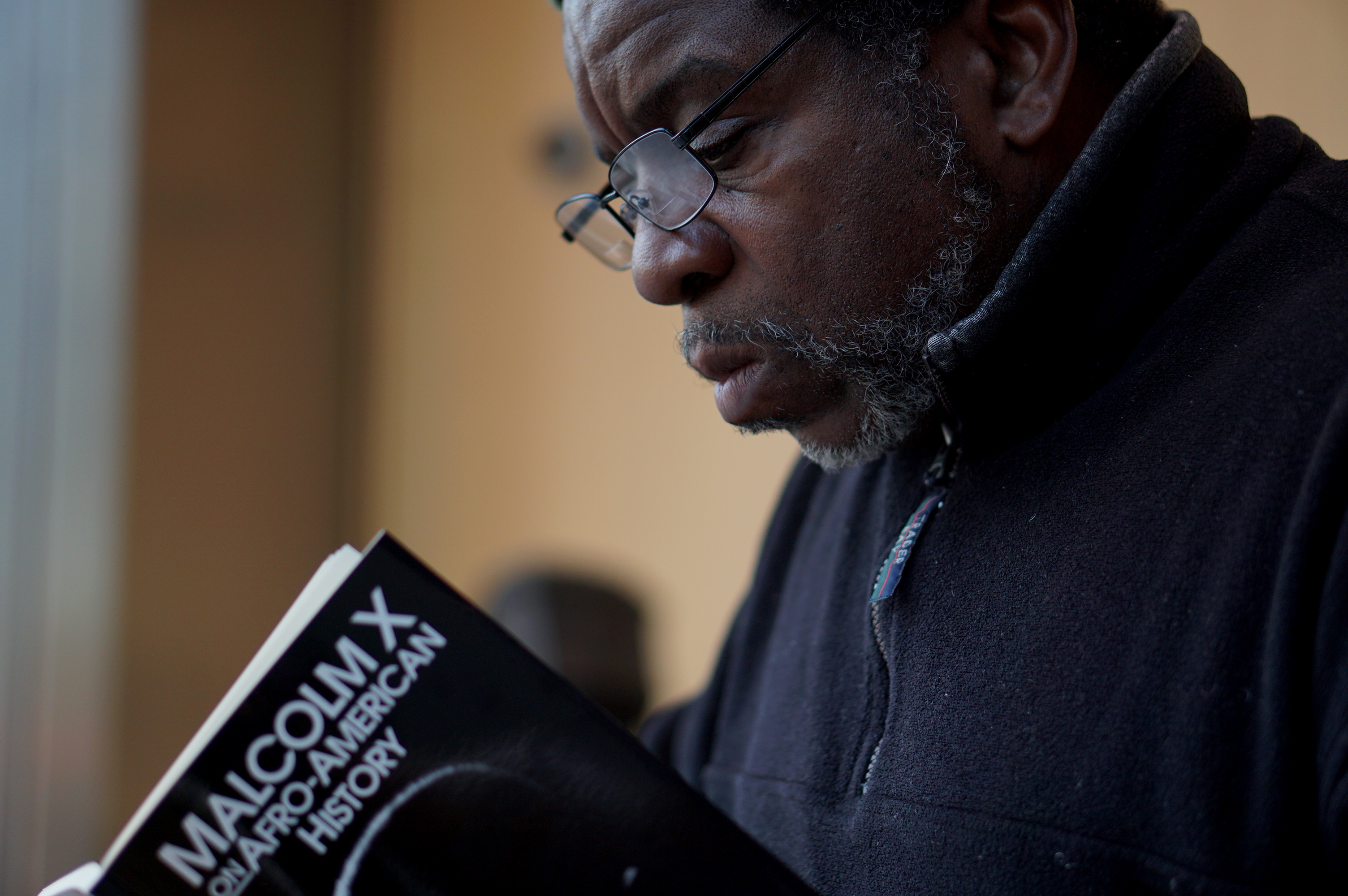

Sister Aisha al-Adawiya still remembers the first time she heard Malcolm X speak.

“I don’t think I have the words to describe the atmosphere. It wasn’t a religious setting as much as a political awakening. People were hearing - often for the first time, about their history and who they were before enslavement. It was like a shot of pride just running like an electric current through the people.

“I was in my early twenties. The auditorium was packed. We were patted down. There were so many people in one room. We couldn’t even see him, but we could hear him speak … it was simply mesmerising.”

The 74-year-old says people walked out of his lectures feeling empowered to make a difference in their life right then and there. She said she was personally taken by his social critique and his allusion to the struggles of others around the world.

“This was the early sixties. Everybody would come. People were struggling in life. So many drugs. So many problems. They were transformed overnight. It was incredible to be in his presence,” al-Adawiya, a long-time community organiser and scholarship officer at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, says.

Malcolm X, also known as el-Hajj el-Malik Shabazz, was born as Malcolm Little in 1925. After losing his father in 1931 and being placed in foster care due to the illness of his mother, Malcolm entered a world of crime and was imprisoned for robbery in 1946.

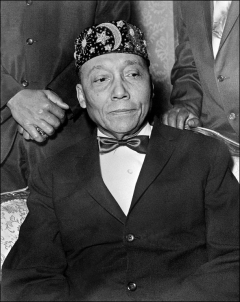

In prison, he was introduced to the Nation of Islam (NOI), a radical Black Muslim movement and became influenced by the teachings of its leader Elijah Muhammad.

What is the Nation of Islam?

+ Show - HideThe Nation of Islam was formed by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930. The group combined Black nationalism with some elements of Islamic theology in their quest to address racial inequality and the human rights concerns of African Americans. The group said that the Trans-Atlantic slave trade had robbed African Americans of their history and their original faith: Islam.

Elijah Muhammad, its leader for 41 years, was considered by the Nation as a 'prophet of God' which violates Islamic fundamentals. The Nation also advocates for racial separation in stark contradiction with orthodox Islamic values that place value on universalism. Though the group identify as Muslims, they are not recognised as such by the mainstream Muslim community in the US or around the world.

After Muhammad died in 1975, his son Warith Deen Muhammad took over and diluted the organisation, moving its members into orthodox Sunni Islam.

The Nation of Islam was revived by Louis Farrakhan, who leads the group and an estimated 20,000-50,000 members, today.

The Nation preached separatism and economic self-sufficiency for the Black community. Malcolm embraced the group’s ideology, and spent his time in prison studying English, Latin, and the dictionary prodigiously. He also joined the debating team where he thrived.

When he was subsequently released, he met with Muhammed, who was so impressed with Malcolm’s oratory brilliance that he made him a minister and national spokesperson for the group.

Malcolm quickly became known as a fiery speaker with an ability to stand tall and call out white supremacy at a time when the wider movement for Black civil rights was still fighting for traction.

Within a few years, he had helped to put the Nation on the map, with the organisation opening up temples all across the country and drawing thousands to join their ranks. Malcolm pushed the “separatist” agenda of the Nation as well as spouting its belief that “the white man is the devil”.

After 12 years, he broke with the Nation of Islam in 1964, over a series of differences concerning the direction of the group and his role within it. He was also shocked and disillusioned by Elijah Muhammad's infidelity.

“He was a staunch nationalist and anti-integrationist, but after the Hajj, you can see his approach was more about systems and it was internationalised,” Richard Benson, an associate professor at the Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia, told Middle East Eye.

His departure from the Nation heralded in a new era of Malcolm. He had embarked on the Hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca, in April 1964 and the experience proved to be transformative.

In a letter sent from Mecca, Malcolm wrote: "There were tens of thousands of pilgrims, from all over the world. They were of all colours, from blue-eyed blondes to black-skinned Africans. But we were all participating in the same ritual, displaying a spirit of unity and brotherhood that my experiences in America had led me to believe never could exist between the white and the non-white.

"You may be shocked by these words coming from me. But on this pilgrimage, what I have seen, and experienced, has forced me to rearrange much of my thought patterns previously held, and to toss aside some of my previous conclusions."

His call for Black empowerment veered into larger, wider critiques of American imperialism and capitalism.

He was also open to alliances. In speeches in Accra, Ghana, on 13 May 1964 and later at Oxford University on 3 December 1964, he articulated his belief in the need for a radical transformation of the world’s economy, and why he believed that violence was justified to thwart oppression.

“I don’t believe in any form of unjustified extremism. But I believe that when a man is exercising extremism, a human being is exercising extremism in defence of liberty for human beings, it’s no vice. And when one is moderate in the pursuit of justice for human beings, I say he is a sinner,” Malcolm said during the debate at Oxford.

“People think that his willingness to make alliances meant that he was succumbing to [“integration”] but he just meant that he wouldn’t hold blanket prejudice on all people of European descent … he wanted to dismantle systems of oppression,” says Benson, the author of a book on Malcolm X’s influence on student movements in the 60s and 70s.

Alden Young, director of the Africana Institute at Drexel University in Philadelphia, said the idea that Malcolm was moving towards a facile notion of “integration” is false. “If he was moving towards Martin Luther King Jr., it’s because they were both merging against imperialism.

“I think he believed that it would be through closer connections between African Americans and Africans abroad that you would see economic development.”

Malcolm travelled to Kenya, Egypt, Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Uganda, Guinea and even to Palestine (Gaza) where he met with the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO).

And given that these words were spoken during a time when so many African nations were also staring at the dawn of their own political independence, his words not only resonated with Black America. They reverberated across the oceans, too.

“We knew we were in the presence of something special. And if we missed his lectures, we were reading his ‘Muhammed speaks’ [a publication of the Nation] which he pretty much wrote on his kitchen table. It was all like a classroom,” al-Adawiya says.

In the early 70s, al-Adawiya can’t remember the precise date, she converted to Islam. “As I got more involved, things just started changing for me. I changed my diet. My dresses started getting longer. I started covering my hair. I stopped smoking cigarettes and drinking wine, and then I took the Shahada (the Testimony).”

“And when I was asked why I became Muslim, I found myself saying: “Well, I am just following Malcolm.”

'Islam in America as we know it wouldn't exist without Malcolm'

“It bothers me when Malcolm X is not properly honoured,” says Palestinian-American Imam Omar Suleiman.

The 33-year-old Suleiman, based in Dallas, known for his civil rights activism, says a lot of Muslims like to prove how deep-rooted Islam is in America by pointing out that many slaves who had come to America had been Muslim.

“But they forget that Islam in America as we know it, wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for Malcolm.

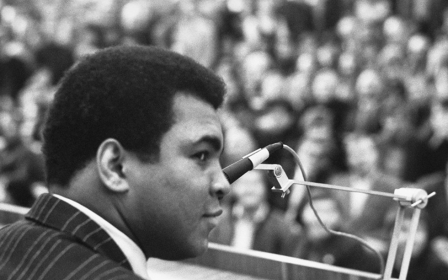

“Malcolm was the biggest reason for the growth of the Nation of Islam and the biggest reason for the continuation of Islam in the African-American community … [The legendary boxer Muhammad] Ali said he probably wouldn’t have been Muslim if it hadn’t been for Malcolm,” says Suleiman, who also teaches "Islam and the American Civil Rights Movement" at the Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

Following the death of the leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, in 1975, his son Imam Warith Deen Muhammad followed Malcolm's lead and integrated the Nation into mainstream Sunni Islam, taking most of Nation's followers with him. Though the Nation still exists today, it is little more than a fringe group, with no theological legitimacy within orthodox Islam.

The Malcolm Shabazz mosque in Harlem, built in 1946 by the Nation, was initially known as Temple No. 7 and later Mosque no. 7. This is where Malcolm X spent much of his preaching as a Minister of the Nation.

It was bombed in 1965, following Malcolm’s assassination, and the Nation moved it to another part of town and Mosque 7 was rebuilt. In 1976, Imam Warith Deen Muhammad decided to honour Malcolm by renaming it the Malcolm Shabazz Mosque.

Almost 50 percent of Black Muslims are said to have converted during the course of their life.It is estimated that there are around 3.5 million Muslims in America today, making up 1.1 percent of the population. Muslims are diverse with no one race group dominating the faith. One in four Muslims in America today are African American, with Arabs and Asians and whites making up the rest.

Atiya Husain, an assistant professor at University of Richmond, whose research explores how the figure of Muslims in the post-9/11 era reinforces ideas of blackness and whiteness, said there was no doubt that Malcolm had played a leading role in persuading people to convert.

“Most of the people I interviewed - whether white or Black - said they converted after they had read his autobiography. Second on the list was the Quran. But mostly the autobiography,” Husain told MEE.

Likewise, Edward E Curtis IV, a professor of religious studies at Indiana University, in Indianapolis, said that Malcolm’s work and the memories of him had become a key factor in the association of Islam with Black freedom in the United States.

“He has been as important and if not more important than any other figure [but] it is always dangerous to attribute one person’s conversion to the charisma and authority of a single individual as opposed to a complex social, political, and cultural context,” Curtis said.

Curtis added that while Malcolm X had been deeply embraced by Muslim Americans from a variety of racial and ethnic backgrounds, they sometimes forget the fact that he was a Black radical freedom fighter until the day he died.

“To some Muslim Americans, he is seen only as the man who embraced racial harmony on the Hajj, and that’s his legacy,” Curtis said.

"If you want to celebrate Malcolm, you need to bear his burden. And that means amplifying the causes that were sacred to him. You know his wife Betty asked: When will Muslims claim Malcolm? He was a believer"

- Omar Suleiman

The reluctance to claim Malcolm in his full identity as a Black radical pushing for Black people’s liberation left Malcolm disappointed with the larger Muslim world in the sixties.

“Malcolm argued that non-Black Muslims should fight for liberation of Black Muslims because the Quran is pro-human... and stand up for justice no matter who it’s for. This was Malcolm’s contention with the Muslim world,” said Suleiman.

In 2017, a survey conducted by the Institute of Social Policy and Understanding found that 66 percent of Muslims support the Black Lives Matter movement.

But Suleiman said he was unsure if Muslims fully understand what that support actually entails.

Over the past year, he has been conducting a country-wide seminar-series called “Malcolm X after Mecca”. The seminar typically focuses on the last year of Malcolm’s life, documenting his transformation as a father and husband, a Muslim, and Black leader, whose legacy continues to grow, despite attempts to quash it.

Every seminar has drawn sell-out crowds, most of whom are of South Asian or Arab descent.

“When I chose this subject and decided to teach it on this particular platform, I did that knowing that I would get to speak to a majority non-Black Muslim crowd and connect them to someone that they owe a great deal to.

“I make a point in my class that it is not enough to connect with the great Black Muslim pioneers who have passed on. One needs to connect with the community as it exists today, particularly the community of Imam Warith Deen Muhammad [because] Muslims need to forge meaningful relationships,” said Suleiman.

“If you want to celebrate Malcolm, you need to bear his burden. And that means amplifying the causes that were sacred to him. You know his wife Betty asked: When will Muslims claim Malcolm? He was a believer.”

Ballroom for rent

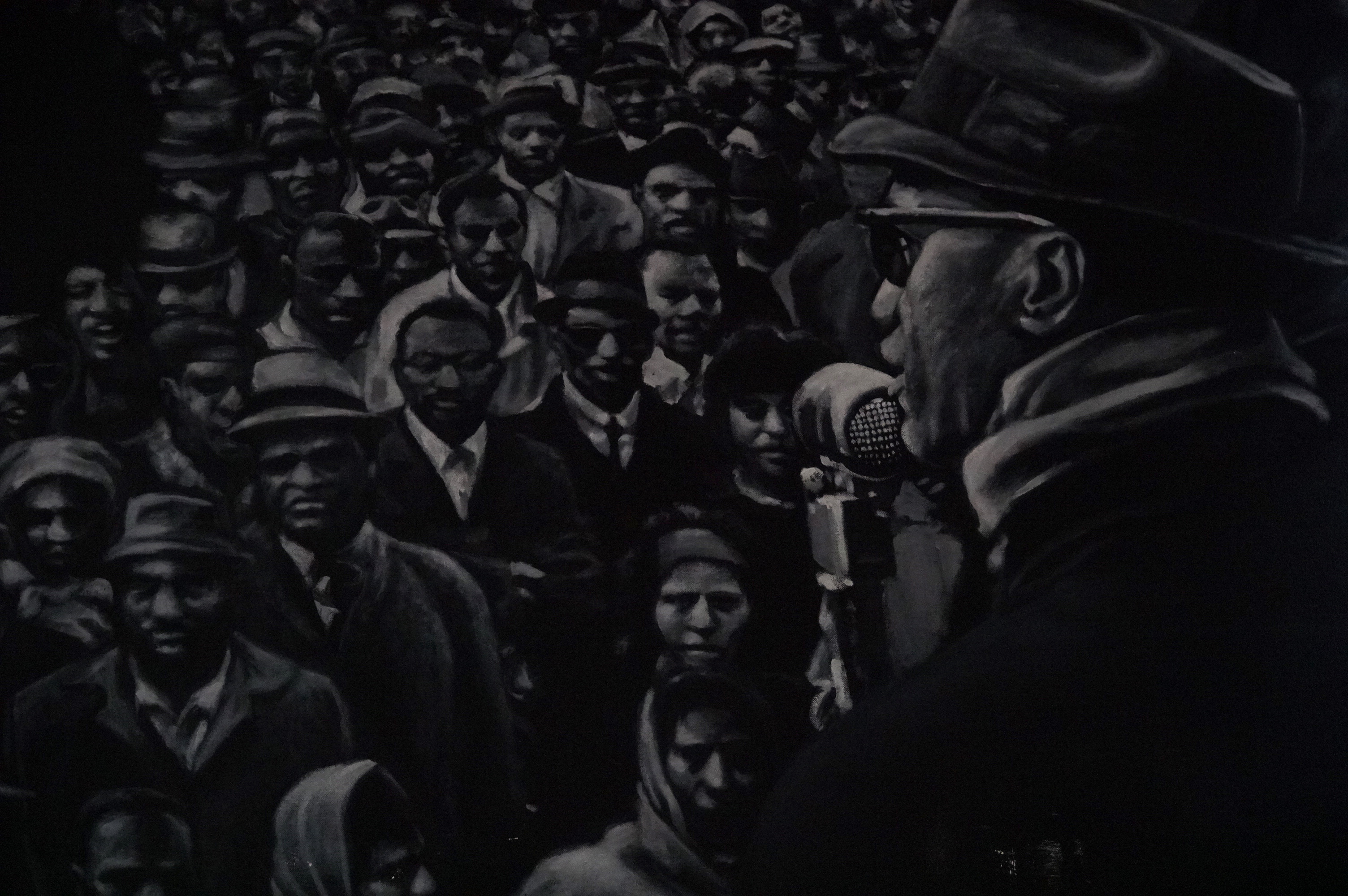

Malcolm X was 39 years old when he was assassinated. His murder took place just as he began to address a group of people at the Audubon Ballroom in the Washington Heights neighbourhood of New York City. Three men, linked to the Nation of Islam, opened fire on him, in front of a crowd of hundreds who gathered to hear him speak. His wife Betty, pregnant with twins at the time, and their four daughters were also in attendance.

“Malcolm was said to have been standing to the right of the podium,” Ruby, the elderly woman, who now looks after the building, which today is known as the Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center.

“He was carried down these stairs, and you see where the toilets are now? There was an exit there, and they took him to the hospital,” Ruby, who doesn't offer a last name, says.

Malcolm X was pronounced dead 15 minutes later.

The cultural centre, home to the final moments of Malcolm X’s life, is analogous to the proud, loud and vibrant personality of the man. The centre is like a mausoleum without a burial chamber. It is quiet. Even the bold, colourful mural in the ballroom cannot cut through the gloomy silence. The multimedia screens in which stories are meant to come to life are not working.

Ruby, herself new to the centre and short of information, says she is curious to see the information on the screens herself. The statue of the Malcolm standing tall and vehemently on the staircase is coarse with dust.

The large plastic banners that spout bite-sized historical insights into Malcolm X are frail and tearing at the edges. Here, his legacy is silenced.

“If you want to host an event here, you can call this number, they are looking to rent the ballroom out,” Ruby says as I head out.

'Treated like a pariah'

Randi Gill-Sadler cannot recall having an in-depth conversation about Malcolm X outside of her home.

The 31-year-old assistant professor at the Department of English at Lafayette College, Easton, Pennsylvania, says as a teenager, most of whatever she learned about the man, happened at home. If he was mentioned at school, it was always as a foil to someone else.

“Even at high school, Malcolm was treated like a pariah. He was someone who was just mentioned in the overall coverage when it came to civil rights movement. But certainly not a leading figure,” says Gill-Sadler, whose doctoral dissertation focused on representations of American imperialism and Black women in US and Caribbean literature.

“I think civil rights history at school level is almost set up to disregard Malcolm.”

“Either his strategies were too radical. Or his approach to race was too abrasive. I think for me, the [Spike Lee] film gave me an alternate way to see this person and not as the opposite to Martin Luther King Jr.”

Sister Aisha al-Adawiya, from the Schomburg Center, says those who want to continue Malcolm’s teachings and advance his legacy are forever battling with “the system” and its attempt to whitewash his memory.

“The more radical elements, even when it comes to Martin Luther King Jr., are often left out,” she says.

“And yes, you can walk outside and you talk to a kid and ask them who Malcolm was, and they may not know. It can be shocking.”

But Malcolm’s legacy has always been difficult to quantify.

"It’s not clear how popular he was after he was ostracised by the Nation and at the time of death,” said Alden Young, the economic historian from Philadelphia.

“Malcolm has a weird legacy, in the US. He had a revival in the 90s with the film and the rise of hip hop. And many claim him today but I am not sure how many of us are actually reading him or have listened to what was actually said.”

Malcolm has his fair share of critics as well, especially among Black feminist historians, with Gill-Sadler pointing out that his views on homosexuality would be considered homophobic today.

“I don’t think people have dealt [enough] with gender politics around Malcolm. I think they assume that it was an area in which he was limited.”

Malcolm’s views and his relationship with women evolved as his political understanding evolved, too.

One of issues that led to his break with the Nation was the sexual exploitation of women by its leader Elijah Muhammad. And this break came at a heavy cost; it cost him his relationship with other members of the Nation who he held in high regard, including Muhammad Ali. It also led to further antagonism with the Nation.

Gill-Sadler said this level of personal sacrifice has resonance with today’s #MeToo movement.

“I think it’s important to bring this back into the discussion as to who Malcolm was and what he actually stood for,” she said.

Malcolm has also been criticised for creating a distinction between 'house Negroes' and 'field Negroes' in which he valorises slaves working in the field and taunts those who worked in the house. "He ['the house Negro'] loved the master more than the master loved himself," he said.

"And the house Negro always looked out for his master. When the field Negroes got too much out of line, he held them back in check. He put 'em back on the plantation. The house Negro could afford to do that because he lived better than the field Negro.

Black feminist historians contend that the analogy doesn’t hold up.

"It obscures the kind of violence and sexual violence enslaved people who worked in the house - which were usually Black women - would have experienced as a result of their proximity to their ‘master'," Gill-Sadler says.

“But what Malcolm was really trying to point to - and it’s important to talk about it today - was the way in which the US government and white supremacy will incorporate selected Black people to further its agenda.”

"We have had Black people occupy some of the highest political positions - but we see racism on the rise. I won’t use his analogy - but his point was prophetic in some ways.”

'White supremacy is global'

Atiya Husain, an assistant professor at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at University of Richmond, says teaching “The life and times of Malcolm X” has been more rewarding and fruitful than anything she could have imagined.

Given the dimensions of Malcolm’s life, his philosophies, his appeal to so many different groups - be it Black radicals, Muslims, leftists, anti-imperialists, Black conservatives, amongst others - Husain was concerned that she would have to string together a course that would deal with “everything”.

“Malcolm was involved somehow, however briefly, in just about every major event that happened during his lifetime. He had some relationship to everything I wanted to teach – colonialism, race, capitalism, religion, social movements, gender, sexuality – and his life and legacy brings all these things together in ways that we need to explore more today,” said the 32-year-old.

Husain is one of many young scholars and academics who are bringing Malcolm into the classroom more than ever before. She says that most of the 23 students in her class are persons of colour - unusual for a university that is predominantly white.

“Black students can relate with what he is talking about - it does not need to be explained. They feel it,” she said.

“I am hoping that students get a better sense of mid-20th century movements, a better understanding of religion. One of the bigger ambitions is to get them to see race as a global phenomenon - that white supremacy is global.”

There have also been an increase in annual events in NYC marking the life of Malcolm. Both the Schomburg and The People’s Forum will host seminars this week marking the death of the icon.

In mid-2018, the Schomburg acquired important manuscripts related to Malcolm’s autobiography, including an unpublished chapter from the book. These sources, the Schomburg says, will provide researchers with new insight into the man and his thinking.

“There is a still lot of work to do. But Malcolm lives. He is more powerful now, in death, than he was walking among us.”

'Malcolm was ahead of his time'

The young man in the black jacket, black track pants and black sneakers, returns from his late-afternoon prayers. We walk outside the Malcolm Shabazz Mosque and settle on a space on the sidewalk between the entrance of the mosque and a barbershop. His full name is Malcolm Bey.

“My parents named me after Malcolm X. I must have been around seven-years-old when I watched [Spike Lee’s] movie “Malcolm X” and understood where it had come from.

“I just remember thinking for someone to come from the hells and bowels of North America and then be one of the most powerful men in the world - it inspired me - to be something more than what people thought of the average African American,” says Bey, who now works in New York City on blockchain currency.

He says reading Malcolm X in his teens made him understand that he alone was the “master and slave of my destiny.”

“It’s not the sixties no more, conditions for Black people haven’t changed. It’s just the packaging of racism has changed… you have the United Nations some blocks away but [look at the] conditions here, or uptown in the Bronx - some people don’t even have hot water.”

“They living here in subhuman conditions in New York City, bro. And it’s not just Black people. It’s Latinos also. Anyone who is not white … Malcolm was ahead of his time.”

“That’s why I came by to this mosque. His spirit is here,” the 32-year-old says.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.

![Aisha al-Adawiya Aisha al-Adawiya says that people are slowly opening up about Malcolm, but it's still a work in progress [Azad Essa/MEE]](/sites/default/files/aisha.jpg)

![Malcolm Shabazz mosque The Malcolm Shabazz Mosque is located in the heart of Harlem and home to a large West African community [Azad Essa/MEE]](/sites/default/files/dsc07956.jpg)