Why executions in Egypt are skyrocketing and why they should end

Egypt has been moving fast to execute detainees, with President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi himself apparently backing this terrible spike in death sentences in 2019.

Recently Sisi lectured his critics, including European leaders, at the Arab-EU summit in Sharm el-Sheikh, suggesting that executing detainees is part of “our humanity”, which is different from “your [European] humanity”.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Yet when speaking about values, the president's justification speaks little truth, and aims to conceal an unprecedented crisis in Egypt’s recent history. Under Sisi, Egypt’s use of the death penalty has soared, with thousands of death sentences ordered since 2013.

This escalation is actually a break from past practices observed even under former President Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year authoritarian rule, of commuting or halting some death sentences, and even under former President Anwar Sadat whose assassins were never executed.

This surge should bring significant scrutiny, but Sisi’s government has worked to quash any free dialogue about the death penalty, while working in tandem to silence organisations that shed light on human rights abuses.

Disinformation campaign

Since 2014, when Sisi became president, Egypt has been among the 10 countries with the highest numbers of annual executions, joining other notorious executors of the death penalty like China, Iran and Saudi Arabia.

And since 2014, criminal and military courts have issued more than 2,500 initial death sentences, hundreds of them in cases of alleged political violence, which are usually marred with severe due process violations.

In comparison with past practice, an international rights group found that Egyptian criminal courts had issued 530 death sentences between 1991 and 2000, which was also a period of political violence in Egypt.

Right now, there are about 50 people who are at risk of execution at any moment, after their death sentences have been confirmed by military or civilian appeals courts.

As part of his disinformation campaign, Sisi has aimed to portray human rights values as “Western” and “foreign” to Egypt. In fact, many brave Egyptians have for years campaigned against the death penalty, including lawyer Nasser Amin, anthropologist Reem Saad and historian Khaled Fahmy, among others.

Sisi has tried to portray the death penalty as a broadly accepted practice, but in reality, its use has been declining worldwide. According to a 2015 UN report, around 160 countries - including countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America and many Muslim countries- have ended the death penalty in law or in practice.

In 2017, Egypt was among only 23 countries that have carried out executions.

This was a big move for the judiciary towards becoming a tool of oppression

So why have executions been skyrocketing in Egypt? The answer to this question is also central to understanding why they should be halted.

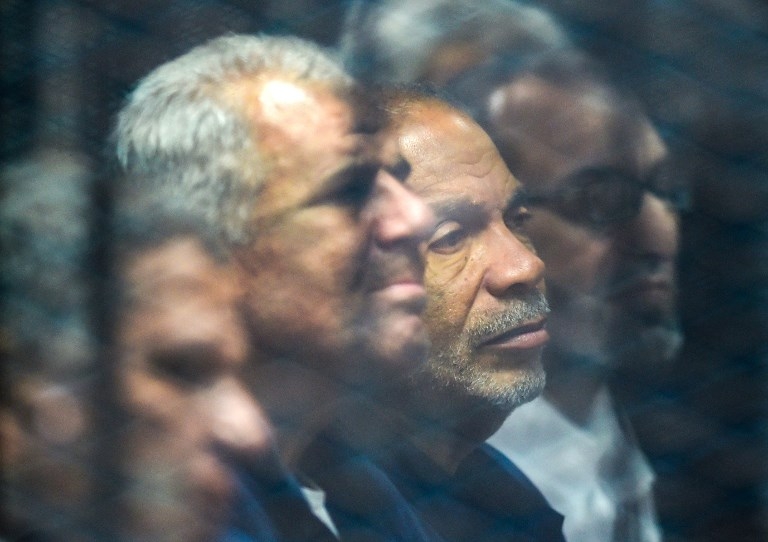

After the July 2013 military coup that forcibly removed Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president, the military-backed government prosecuted thousands of Muslim Brotherhood leaders, members and sympathisers, often in mass trials over alleged political violence.

At that time, the country was still in severe political turmoil and the military rulers had not yet asserted their full control over traditionally independent state institutions. This included the judiciary at that time, where many criminal court judges simply opted to quit overseeing such cases.

Who are the nine men executed in Egypt on 20 February 2019?

+ Show - HideMahmoud el Ahmady, 23, student of translation studies at Al-Azhar University

Ahmed Wahdan, 30, civil engineer

Abulqasem Youssef, 25, student at Al-Azhar University

Ahmed Gamal Higazi, 23, Student at Al-Azhar University.

Abubakr Ali, 24, student at Zagazig Universiry.

Abdulrahman Sulaiman Mohamed, 26, sales representative

Ahmed el-Degwy, 25, student at the Modern Academy in Cairo.

Ahmed Mahrous Abdelrahman, 27, student at Al-Azhar University

Islam Mohamed Mekkawy, 25, student at Al-Azhar University

In response, in late 2013 the government created special “terrorism courts” within the criminal court system and assigned willing judges to oversee cases of alleged political violence.

This was a big move for the judiciary towards becoming a tool of oppression and a major attack on the judiciary’s independence. These so-called terrorism courts, particularly a handful of judges, issued hundreds of death sentences.

Hands 'tied by laws'

But the Cassation court, Egypt’s highest appellate court, continued to act as a relatively strong check on those flawed convictions by overturning many of them between 2014 and 2016.

As a highly respected court, it was hard for the government to undermine its independence - at least until the assassination of Hisham Barakat, the former prosecutor-general, in June 2015.

At his funeral, Sisi remarked: “The hand of justice is tied by laws… We cannot wait for that.” Furiously critical of the judges present around him for slowing down the implementation of his own vision of "justice", the president pledged to amend the country's laws.

He kept that promise.

In April 2017, Sisi approved amendments to Egypt’s Criminal Procedural Code and the law concerning appeals in order to circumvent the Court of Cassation - developments that Amnesty International described as a “nail in the coffin of fair trial standards”. On the same day, Sisi also passed a law that gave him a tighter control over appoint the Cassation Court’s chef judge.

Since then, the Cassation Court’s role in overturning flawed death sentences has been severely diminished, and it has upheld scores of them.

Additionally, and even before Barakat’s assassination, Sisi had issued an unprecedented law in October 2014 that extended the jurisdiction of military courts to prosecute civilians.

Since then, over 15,000 civilians have been referred for military prosecution, leading to scores of additional death sentences by inherently unjust courts.

Public criticism

Since 2011, Egypt has been undergoing an intense political turmoil. And while there is no evidence that the death penalty deters serious crimes, executions, especially in cases of alleged political violence, only widen the sense of injustice, especially since there is neither any vision nor any promise for transitional justice.

Let’s not forget that this executions spree is also happening in a country whose security forces have killed hundreds of peaceful protesters since 2011 with near-absolute impunity, and have been accused in incidents of extrajudicial executions of detainees as well.

Egyptian justice is not only so often unjust, but it is “malfunctioning”, to the extent that a judge’s signature on a death sentence was found to be forged.

Trials are systematically flawed, with one judge sentencing more than 500 people to death in one case, and another sentencing a four-year-old toddler to life in prison, in what was later called a "mistake".

There is a serious concern that after several years of rolling back due process protections, and eroding the independence of the judiciary, the floodgates are set to open for a wave of executions conducted after massively unfair trials.

What’s needed is not patiently listening to Sisi’s fact-free lectures about human rights values in Egypt, but rather sustained and public criticism, including by Egypt’s allies, against the government’s apparent desire to carry out more death sentences against victims of a broken and flawed judicial process.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.