Arabic poetry: 10 writers, classic and modern, you need to read

Poetry has always been at the heart of Arabic culture, not least as the oldest means for its earliest speakers to record their beliefs and wisdom, oral narratives and philosophy.

It began in the Arabian peninsula more than 1,500 years ago, predating Islam, but has now become a global art form.

Historically, its reach has relied on the extent of Arab states and Muslim influence. Andalusian poetry, for example, died out in the Iberian peninsula after the fall of Granada in 1492, but its form and style still inspire 21st-century poets in Morocco 500 years later.

Arabic poetry is most popular when it is shared in public, from cafes and festivals to weddings and funerals

For centuries, the classic Arabic poem was dominated by the ode – a poem directly about someone or something. Then, during the 1940s, Iraqi poets such as the pioneering Nazik al-Malaika, started to adapt a modern approach that mixed classical structure with western influences including TS Eliot.

Contemporary poetry is now written wherever Arab poets live, be it at home or overseas, in exile or in refugee camps.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

During the past two decades, digital platforms have helped the spread of its appeal, rekindling its popularity. But it is never more popular than when it is read and shared in public, from cafes, arts festivals and radio broadcasts to TV shows, weddings and funerals.

Arabic poets write in a variety of forms and styles, including the classic ode, the modern ode and free prose. There is also room for works and recitals in colloquial Arabic, especially in Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Morocco and Jordan, where it finds a broad audience.

How poems relate to the world

Writing poetry, like reading and discovering it, is an act of adventure and astonishment led by intuition and a love of words. It is a personal journey.

Contemporary Arab poets may write in more varied forms and styles than ever before, but they still capture the essence of our age, using Arabic lyricism, metaphors and images in conjunction with twists and astonishment to captivate readers and listeners.

Many modern writers in the Arab world began their literary careers by practising poetry, including Iman Mersal, Nouri al-Jarrah, and Maram al-Masri.

In doing so they gained a sense of Arabic’s rhythm and precision, taking care with their words, seeing the world afresh and looking for the transcendental beyond the banal.

Poets are also furious defenders of the human soul whenever it comes under attack from tyranny and totalitarianism. One of Mahmoud Darwish's famous poems, Write Down! I Am An Arab, was written after he was released from an Israeli prison in the 1960s.

Yet too much Arabic poetry has yet to be translated into English. In preparing this selection, for example, it was surprising not to find a volume of works by al-Mutannabi, who some regard as the greatest Arab poet who ever lived. There will always be a gap in any Anglophone library of literature if his poems, and accompanying commentary about his life, are absent from the bookshelf.

Summarising the history and geography of Arabic poetry is no easy task. The poets below are listed in no particular order and only offered as a gateway to a wider world. Feel free to share your own favourites on MEE’s Twitter and Facebook pages, also the hashtag #worldpoetryday.

Classic poets

1. Imru' al-Qais (501-565)

Heir to the throne of the Kindah tribe, which was based in the Arabian peninsula, al-Qais chose a life of travelling, drinking, fighting – and poetry.

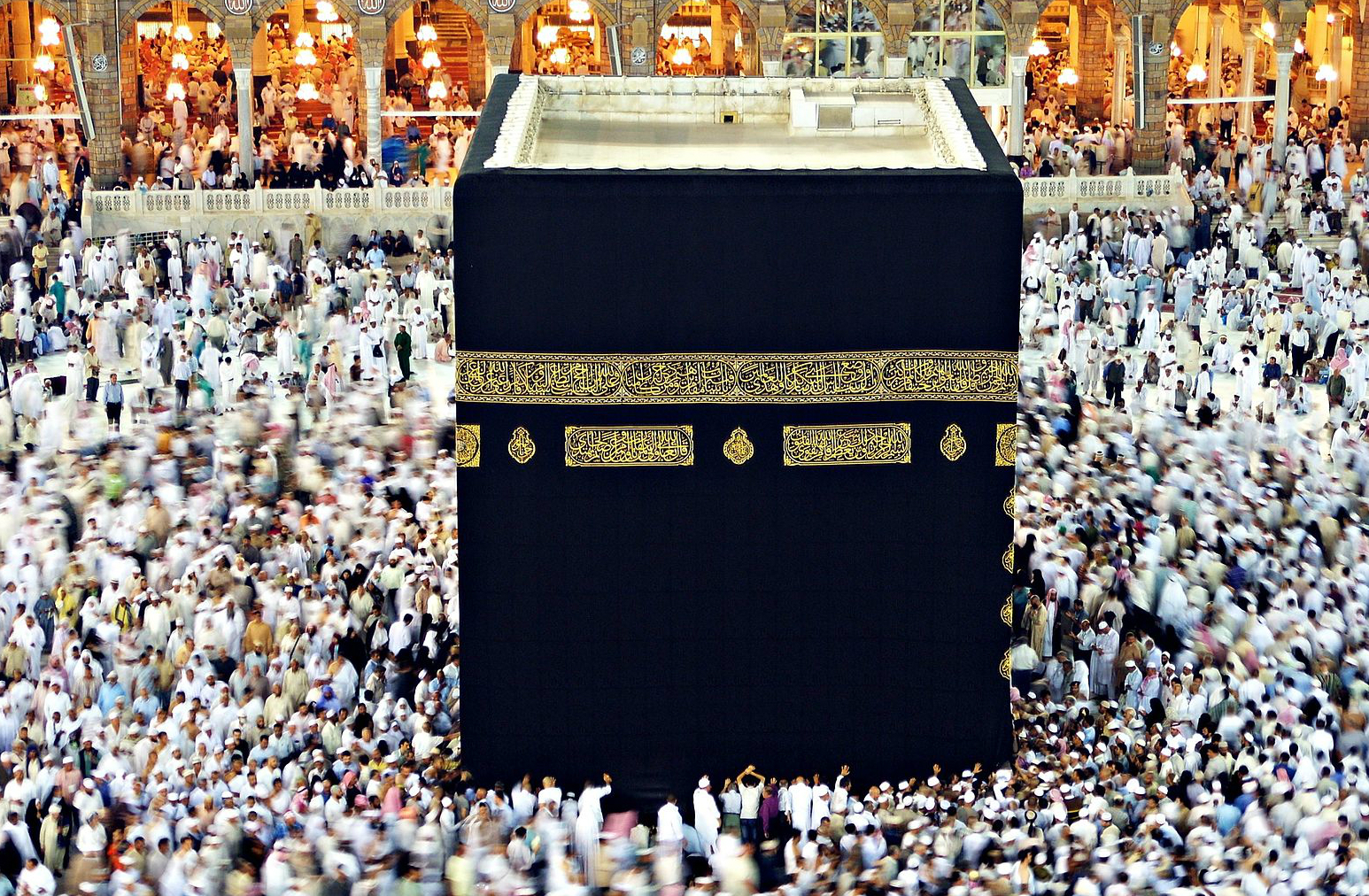

His masterpiece is the Mu'allaqa, an ode so revered that it is written in gold on sheets of paper which are then hung on the walls of the Kaabah in Mecca, Islam’s most revered shrine (its name translates as "hung ode").

Other poets may have their own famed works, but al-Qais is considered by many to be superior because of his astonishing metaphors and beautiful verses, which echo his desire to be a worthy lover, wise man, warrior and master. Such work, which he perfected, has gone on to heavily influence the writing of those who followed.

May You Be Happy This Morning, Worn Traces!

How many a day, a night I'd spend

with a woman, stark as a statue outlined,

her face aglow as she turns to her mate

like softly radiant candle light;

her breast like the flare of a generous fire

by chilled men lit in the desert at night

in the wind come roving across the hills,

north, south, at the caravan staging posts.

Clear-cheeked, in her teens, so playful yet

that she makes me forget my clothes when I leave;

with rounds like the dunes that as children we loved

to tread for their smooth and velvety touch.

When her lover strips her, wanting all,

she leans to him lightly, holding back;

slim at the waist and firm as she twists

with quickening breath from intoxicant lips.

Translation by Charles Greville Tuetey from Imrulkais Of Kinda, Poet, Circa A. D. 500-535: The Poems, The Life, The Background

2. Al-Khansa (575-645)

Tamadir bint Amr, better known as al-Khansa, is one of the Arab world's famous female poets, converting to Islam during the lifetime of the Prophet Mohammed.

Her masterpiece is her eulogies to her brother Sakhr, a tribal chief who was severely wounded and later died after a raid against the rival Bani Assad tribe.

Her verses are full of fine metaphors about loss, life, love and departure. Yet, while four of her children were killed during Muslim battles against the Romans and Persians, al-Khansa refused to write any eulogies to them, saying that Islam had taught her not to wail for the dead.

Elegy for Sakhr

Be generous, my eyes, with shedding copious tears

and weep a stream of tears for Sakhr!

I could not sleep and was awake all night;

it was as if my eyes were rubbed with grit.

I watched the stars, though it was not my task to watch;

at times I wrapped myself in my remaining rags.

He would protect his comrade in a fight, a match

for those who fight with weapons, tooth, or claw

Amidst a troupe of horses straining at their bridles eagerly,

like lions that arrive in pastures lush.

Translation by Geert Jan Van Gelder from Classical Arabic Literature: A Library of Arabic Literature Anthology

3. Abu Nuwas (756-814)

The reputation of Abu Nuwas in the Arab world is built on his adoration of wine and as the poet of gay love.

Born in Ahvaz, in modern-day Iran, he moved at a young age to Iraq, the governing seat of the then-mighty Abbasid Caliphate.

Around 1,500 of his verses survive, including several masterpieces which reflect his experience of cosmopolitan life in Baghdad where nations gathered in taverns, libraries, bazaars, mosques and bath houses.

His work is punchy, spontaneous and full of sharp twists as he vocally celebrated pleasure, male lovers, wine, music and good company, while despising war and the clash of swords.

Abu Nuwas was close to the entourage of the Caliph Al-Ma'mun, entertaining him and his followers with jokes, anecdotes and lustful verses. On his death bed he repented his sins and died as a Muslim.

Karkhiyya

Praise the wine for its munificence

And give it the best of names

Do not allow water to subdue it

Nor let it rule the water

A Karkhiyya* that had long been aged

Until most of it is reduced

Such that the drinker coming by it

Has but the tail-end of its life to enjoy

Yet it turns round and revives blameless

The spirits of ardent lovers

Oft the wine is drunk

By such as are not up to it.

[ *Karkhiyya was where fine wine was produced in Baghdad]

Translation by F Matthew Caswell from The Khamriyyat of Abu Nuwas: Medieval Bacchic Poetry

4. Al-Mutanabbi (915-965)

The life of Al-Mutanabbi is perhaps best described as an epic journey to glory, money and power.

Through his near 300 poems, he mastered Arabic verse like no other and treated poetry as a craft to be studied and taught, through work that spoke of wisdom, pride, courage, fighting the Romans and worshipping one's ego.

Many of his verses are used today as proverbs to reflect on life experiences of friendship, love, departure, war and death.

Born in Kufa, Iraq, as Ahmed bin al-Hussein al-Kindi, his nickname translates as "he who would be a prophet”.

He never rested in one place, travelling to Baghdad, Damascus, Tiberias, Antioch, Aleppo and Cairo among others, earning income from emirs for his poetic praise for them.

Al-Mutanabbi was killed by bandits while travelling from Ahvaz in modern-day Iran: his influence at the time was such that news of his death reverberated like thunder around the Muslim world.

Excerpt from Sayf Al-Dawlah's Recapture Of The Fortress al-Hadath

Firm resolutions happen in proportion to the resolute,

and noble deeds come in proportion to the noble.

Small deeds are great in small men's eyes,

great deeds, in great men's eyes, are small.

Sayf al-Dawlah charges the army with the burden of his zeal,

which large hosts are not strong enough to bear,

And he demands of men what only he can do -

even lions do not claim as much.

Does "Red" al-Hadath know its colour, does it know

which of the two wine-pourers was the clouds?

White clouds have watered it before he came,

and then, when he drew near, the skulls drenched it again.

Translation by Geert Jan Van Gelder from Classical Arabic Literature: A Library of Arabic Literature Anthology

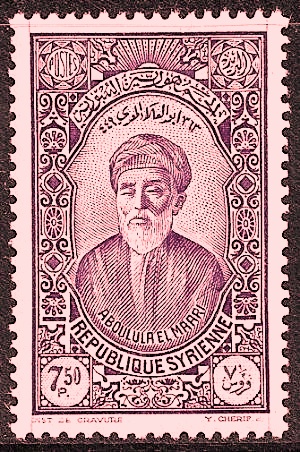

5. Abu al-Alaa al-Maarri (973-1057)

When he was four, al-Maarri went blind due to smallpox. It left him housebound for much of his life: unlike his hero al-Mutannabi, al-Maarri did not leave home for almost four decades, preferring solitude to mingling with people.

His poetry encompasses philosophy, contemplation and pessimism: to many followers, who flocked to his home, he was regarded as the poet of philosophers and the philosopher of poets.

Al-Ma'arri's masterpiece is The Luzumiyat and the Resalat Al-Ghufran (The Epistle of Forgiveness), which focuses on the experience of poets in hell and paradise more than 200 years before Dante's Divine Comedy.

But opponents condemned al-Maarri for heresy because he mocked the followers of all religions. The attacks occurred not only during his lifetime but long after his death: in February 2013 – a thousand years after he was active - Syrian militants decapitated a statue of the philosopher poet in his hometown of Maarrat al-Numan in Syria.

Two epigrams about death and belief

We laughed, and O how foolish was our laughter!

Dwellers on earth should cry and never cease.

Time's vagaries crush us like glass; thereafter

We'll never be remoulded as one piece.

***

If after death your body kept its shape,

We might hope it will be revived again,

Just as a jug, emptied of wine, could be

Refilled, as long as it remains unbroken.

But all its parts have come undone and turned

To particles of dust swept by the winds.

Translation by Geert Jan Van Gelder from Classical Arabic Literature: A Library of Arabic Literature Anthology

Modern poets

6. Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008)

Considered the leading light of his generation, Darwish has been translated more than any other modern Arabic poet into English.

He was born in the Palestinian village of al-Birwa under the British mandate but fled as the Israeli authorities took control and displaced thousands of Arabs.

In much of his work he mixed modern poetry with Arabic rhythmical meters: subjects included the Palestinian revolution of 1965-1993 and the mass exodus of 1948, known as the Catastrophe or Nakba.

Darwish won several prestigious international awards, among them the Prince Claus Fund in 2004.

Excerpt from The Eternity Of Cactus

He felt for his key the way he would feel for

his limbs and was reassured. He said

as they climbed through a fence of thorns:

Remember, my son, here the British crucified

your father on the thorns of a cactus for two nights

and he didn't confess. You will grow up,

my son, and tell those who inherit their guns

the story of the blood upon the iron...

- Why did you leave the horse alone?

- To keep the house company, my son

Houses die when their inhabitants are gone...

Eternity opens its gates from a distance

to the traffic of night. The wolves of the wilderness

howl at a frightened moon. And a father

says to his son: Be strong like your grandfather!

Climb with me the last hill of oaks,

my son, and remember: Here the janissary fell

from the mule of war. So be steadfast with me

and we'll return.

- When, father?

- Tomorrow. Perhaps in two days, my son!

Translated by Jeffrey Sacks from Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone?

7. Iman Mersal (1966 - present)

Mersal is an Egyptian poet and currently a professor of Arabic Literature at the University of Alberta, Canada.

Mersal's poems delve into the personal and banal but then morph into metaphors about life, travel and motherhood.

She writes free prose, a style of poetry which is not metered by the Arabic rhythm: These Are Not Oranges, My Love, a selection of her works, was published in 2008.

Excerpt from These Are Not Oranges, My Love

What you learn here is not different from what you learned there:

You read to absent reality.

You hide your shyness behind foul language.

Camouflage your weakness by lengthening your fingernails.

Suppress anxiety by smoking all the time and by organising, and

reorganising the contents of drawers sometimes.

Use three kinds of eye drops to clarify vision then enjoy the ensuing

blindness. Most important is that wondrous moment of closing your

eyelids as a fire breaks out.

Here and there

life exists only to be watched from a distance.

Translated by Khaled Mattawa from These Are Not Oranges, My Love

8. Nouri al-Jarrah (1956 - present)

Al-Jarrah, who is Syrian by birth, is best known for his use of free prose, collating a chorus of voices inspired by mythology, folktales and ancient Greek theatre protagonists.

He is currently the editor of Al-Jadeed cultural magazine, dividing his time between London and Abu Dhabi. Recent work translated into English includes A Boat to Lesbos and Other Poems.

Excerpt from A Boat To Lesbos

Come, friends. The sand of the shores gleaming in your eyes, the East rippling golden ears of

wheat in the chopper of your faces. Rise as the high mountains rose in your smooth cheeks.

You swing in my mind as the poplars swung in the wind of your days and the apple blossoms

scattered in the gale of your crossing. Come into the darkness of Lesbos, you Syrians who

emerged from the broken tablet of the alphabet.

Translated by Camilo Gomez-Rivas and Allison Blecker from A Boat To Lesbos

9. Mohammed Abdel Bari (1985 - present)

Originally from Sudan, Abdel Bari grew up in Saudi Arabia and is considered one of the most influential voices in contemporary classical Arabic poetry.

His work brews with Sufism and Arabic myths as well as Quranic stories and Islamic philosophy.

He has published three poetry collections and won several international honours, including the Arab African Youth award in 2016, although his work has yet to be translated into English.

If you like listening to the music of the Arabic tongue, check out his recital of What Has Not Been Told By Zarqa' al-Yamam above.

10. Maram al-Masri (1962 – present)

The prose poems of the Syrian poet Maram al-Marsi reflect on love, exile, nostalgia for her homeland and the war in Syria.

One of the most famous female poets in the Arab world, she settled in Paris after leaving her hometown of Latakia in 1982.

One of her most popular collections, A Red Cherry On A White-tiled Floor, was translated into English in 2003.

Excerpts from A Red Cherry On A White-Tiled Floor

I am the thief

of sweetmeats

displayed in your shop.

My fingers became sticky

but I failed

to drop one

into my mouth.

***

How foolish:

Whenever my heart

hears a knocking

it opens its doors.

***

Desire inflames me

and my eyes glimmer.

I stuff morals

in the nearest drawer,

I turn into the Devil

and blindfold my angels

just

for a kiss.

Translated by Khaled Mattawa from A Red Cherry On A White-Tiled Floor

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.