Mystery of the stones: How Lebanon’s Baalbek ruins are a site for the gods

Perched on a lofty mound overlooking Lebanon’s lush Bekaa Valley sits Baalbek, a city steeped in history and home to the ruins of one of the largest Roman religious sites. Its remaining colonnades have become a national emblem.

The religious complex has attracted travellers over the centuries, seeking to witness and claim the might of the Roman Empire for themselves.

But Baalbek’s 300 years of Roman rule overshadow its 10,000 years of continuous settlement, its prehistoric origins and its role as the wellspring of the valley’s two major water sources – an epicentre of life and fertility.

Its name is formed from two words: Baal, the Semitic lord of the gods and precursor to Zeus and Jupiter; and nebek, the Aramaeic word for sources. The Romans knew it by its Greek name, Heliopolis, meaning "city of the sun".

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Baalbek is also a living, modern city where more than 80,000 people live and work.

'It should not be reduced to the folly of a moment in history, when those massive Roman temples were built'

- Vali Mahlouji, curator

Vali Mahlouji, the curator of “Baalbek, Archives of an Eternity,” is aiming to change this one-sided view of the site. Showing at Beirut’s Sursock Museum, the exhibition traces a tangle of histories, encompassing the site’s mysterious ancient origins, its rise to prominence, western appropriation, its political identity and the contemporary reality.

“Baalbek goes back to the beginning of when man settles and there are not that many that have continuously been settled and had a living history,” says Mahlouji, an independent advisor to the British Museum and London-based curator.

“It should not be reduced to the folly of a moment in history when those massive Roman temples were built, and to then embed the story of those epic and awe-inspiring stone structures.”

Baalbek was not an important city, he explains: it became a home to the gods because of its natural setting, including Ras al-Ain, an abundant source of freshwater. Waters from the Ain-Juj spring nine kilometres away were drawn into Baalbek by canal.

“Baalbek commanded these two big sources that feed into the Litani and Aassi rivers, which flow in opposite directions in the Bekaa.”

The first settlements

Baalbek was first occupied around 10,000BC as one of many tells (the Arabic for mounds) in the Bekaa, which is full of prehistoric and Neolithic settlements.

One of the first items in the exhibition at Sursock Museum is a fragment of a slaked-lime vessel from 7,000 BC, displayed alongside a second-century sculpture of a male torso and detailed pedestals from Heliopolis.

The Roman temple, a Unesco World Heritage Site, was completed between the second and third century as a large religious complex built on top of an older Hellenistic temple. The four known temples – Jupiter, Mercury, Venue and Bacchus after the Roman gods - are some of the largest and best-preserved examples of Roman architecture.

“All temples were erected from limestone cut in quarries in close vicinity,” says archaeologist and project researcher Margarete van Ess.

“The stones for the second phase of Jupiter Temple are especially remarkable because of their extraordinary size. For the podium of the temples, stones were cut up to 20 metres in length and four metres high, which [weighed] about 1,000 tons each.

“The transport of those stones to the temple is a reason why people admired this sanctuary. The Trilithon, which consists of two large stones supporting a third, was mentioned as a remarkable feature in ancient texts. Today, it’s the gigantic dimension of the ensemble that attracts people most.”

These foundation stones, particularly those of the Trilithon, are one of the great mysteries of the ancient world. It’s unknown how these heavy blocks - more than 10 times the weight of the individual blocks which make up the Great Pyramid at Giza - were lifted into place. The uphill slant of the mound rules out carts, levers and pulleys.

The enormous size and weight of the stones (archeologists recently found a fourth, even larger one buried nearby) has led to some interesting local legends about their origins, including that they were used by Solomon for a palace for the Queen of Sheba; or that they were left lying unused due to the Biblical flood.

Majhloul says: “There are even still large blocks lying around as though they are going to be used - prepared blocks for the foundations of a new podium around Jupiter Temple… like an on-going project with bits lying around the city.”

The West arrives

In the 17th century, the West began its colonial expansion into the region - and Baalbek’s Roman complex was ripe for centuries of orientalist appropriation.

With the growth in scientific and archaeological research from the 17th to 19th century, Europeans began classifying, preserving and ultimately claiming the site as their own.

English 17th-century poet Jon Donne described the site in glowing tones: "No ruins of antiquity have attracted more attention than those of Heliopolis, or been more frequently or accurately measured and described."

The economic and political growth of Europe occurred alongside what became a rapid decline of Ottoman power in the 19th century, Mahlouji explains. “The Europeans expand their interests in the roots of their own civilization, beyond the glory of Rome and Greece, into the cradle of civilization, Mesopotamia, and by extension claim their own roots beyond Europe."

An aura of Eastern romanticism drew many artists to the site, which Mahlouji has narrated in the exhibition through Western orientalist paintings of Baalbek. A large screen also scrolls references of Baalbek found in poems, songs, books and scriptures through history.

“They [Europeans] discover the Indo-European languages, which link to Asia, and their notion of Europe expands into Persian, Egyptian, Phoenician," explains Mahlouji.

“As Europe revels in the glories, romanticises the sites, excavates them, they start claiming knowledge of these spaces, in the face of the locals who are ignorant of what they have, their own past and connections to anything.”

Symbol of Lebanon

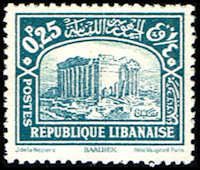

In 1920, the French Mandate decreed the Bekaa was officially Lebanese territory and the grand Roman complex became the emblem of the new nation. Its pillars appeared on stamps, banknotes and postcards - all of which are included in the exhibition.

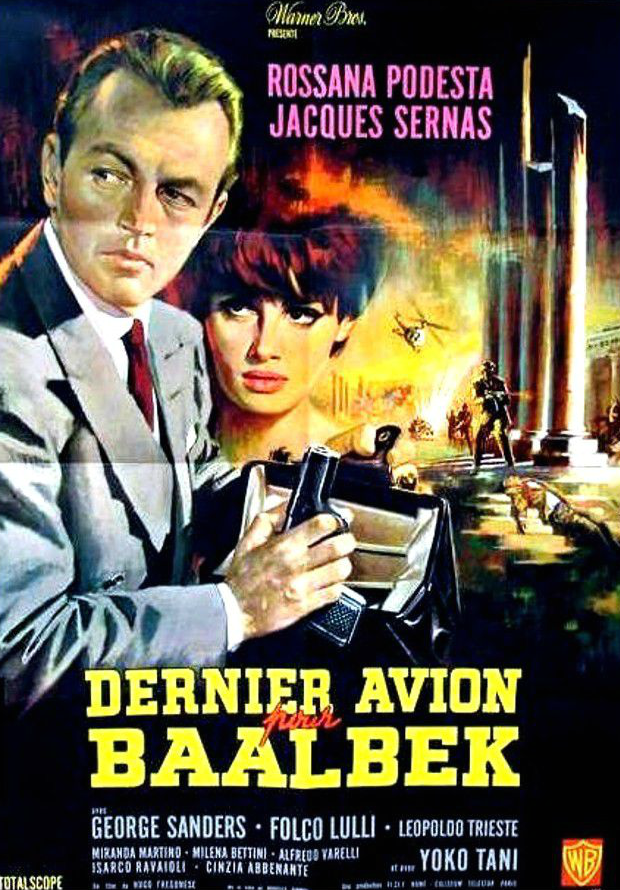

By the 1950s it was featured in film posters and tourism promotions, but its use as a national symbol had political and social ramifications.

“I have a newspaper clipping that says ‘the perfect spot has been found for building the new city and evicting the people of Baalbek,’” Mahlouji said. “One thousand signatures were collected from the people of Baalbek who said they would agree to do it, but there was also resistance, so it didn’t happen.”

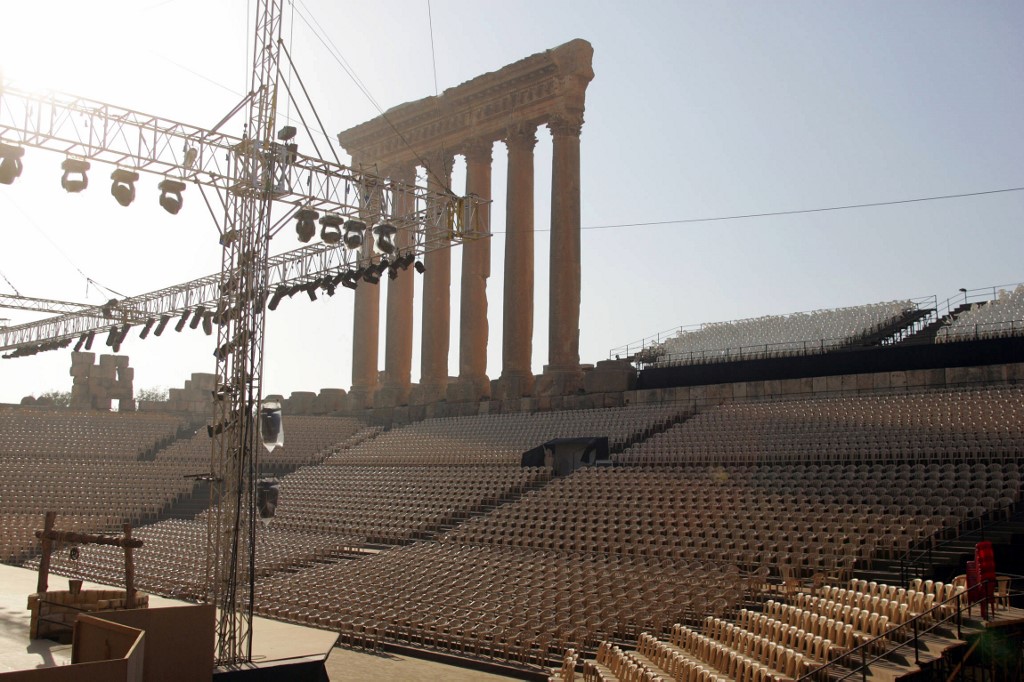

In 1956, in an attempt to bridge the gap, Baalbeck International Festival was born – an annual cultural summer festival running till today, which has hosted the likes of Umm Kulthum, Nina Simone and Sting.

Combining the backdrop of Bacchus Temple with major acts from Europe alongside Baalbeki folklore performances, Lebanon became the link between the East and West.

“The festival is an enduring project that in a way tried to reclaim and reconnect the city with the Heliopolis,” Mahlouji says.

“As if, ‘we need that monument to make sense of things that synthesise everything that’s going to be a modern nation with roots in ancient times,’ but all of that detaches it from where it sits, why it was ever built and what it means to the people who live there.”

In 2019, the divide between the needs of the ancient site and those of modern urban residents still exists, if less pronounced than in the past.

The exhibition’s final sections acknowledge this, asking whether the spirit of Baalbek lies in its ruins or the current inhabitants, who have been living in the area for countless generations.

“If nobody tells me to go I won’t. I don’t feel like it has anything to do with us,” Maen Mazloum, an office chauffeur from Baalbeck, says of the Heliopolis. “The people of Baalbek should be allowed in for free but they charge us 10,000 LBP ($5.70) – my three kids are small and I would like to take them but if we all go it will cost us 50,000 LBP ($33).”

Sipping coffee in a streetside cafe not far from the Roman complex, Mazloum says that while the entrance fee is not a large sum to a tourist, he personally finds it too expensive.

The exhibition also offers testimonies from residents, giving perspectives on daily life, politics and their thoughts on the ancient site versus the city.

Another issue is the tourism: visitors come to the ruins at the north-western edge of the city, yet don’t enter the city proper.

“Nobody comes inside the city either, they’re not allowed to, that’s what the ahzeb (religious political factions in Arabic) and politicians want,” Mazloum says. “We have hotels and nobody is allowed to get a licence to make a hotel around the temples. There is only the old Palmyra hotel and one belonging to Hezbollah that are allowed.”

The Lebanese government has focused on Heliopolis, adding large parking lots and making the site more accessible - but it comes at the cost of the rest of the city’s attractions.

“Traffic in the old town is an issue,” Van Ess says. “The streets are narrow and till today no convincing solution has been found to channel incoming vehicles in a way that doesn’t add to the daily traffic jam.”

Uniting city and site

Mahlouji says he disagrees with the idea of keeping the monument timeless, while the city evolves, separate and ignored – a notion often echoed by the local people.

“What needs to be done is to stop the segregation between what is archaeological, and controlled by the Tourism Ministry, and the living city,” Mahlouji explains. “They’re creating wider roads leading to it, fencing off and making a museum city that is detached from the living city.”

Mazloum agrees. “The municipality needs to do something – make festivals inside the city, allow people to walk in and go to the souks; we have many markets and traders.”

'The temples are for everyone, but it’s in our blood and soul'

- Maen Mazloum, office chauffeur

Instead, the buses stop in the parking lots near the temples. The tourists wander round, then leave for lunch in nearby Zahle.

“They should be having lunch in Baalbek,” he says. “Imagine how much they would be helping the local people – the restaurants, the people who sell necklaces, scarves.

“The temples are for everyone, but it’s in our blood and soul,” he said. “We love it but we’re not encouraged to enter it or be a part of it.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.