Invisible but alive: How the art scene is surviving in Yemen

The conflict in Yemen, now in its fifth year, has been called an “invisible” war. The same could also be said of the country’s art scene: ask an art connoisseur or expert in the Middle Eastern market to name a major modern Yemeni artist and you are likely to draw a blank. “Good Yemeni artists are very few and far between,” said one expert, approached for this piece.

'There’re so many talents but nobody encourages them'

- Khadija al-Salami, Yemeni film-maker

For many in the art world, there are no established 20th-century Yemeni names, no "modern masters" comparable to the Syrian painter Fateh al-Moudarres, or Iraq’s Jewad Selim, whose best works sell for tens of thousands of dollars at auction years after their deaths. In contrast, Yemeni artists rarely make an international impact.

The country’s art scene, like its governments, has in part been hampered by continuously changing borders and political instability. As unrest has descended into war during the past decade, so international cultural organisations like the British Council closed down the spaces it offered for art exhibitions.

Only a scattering of homegrown institutions, like the Basement Cultural Foundation in Sanaa, have managed to hold on.

“There’re so many talents but nobody encourages them,” says Khadija al-Salami, the Yemeni film producer, director and a cultural attache at its embassy in Paris. “They are self-generating. There is nothing that really encouraged them, just an internal force that leads them to do what they do.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In Yemen, she said, art is regarded as “something that’s just wasting your time. It’s: ‘What’s wrong with this guy?”

Artists, art clubs and the USSR

But it is wrong to see modern art in Yemen as without any heritage. The scene had its beginnings in Aden's painting clubs of the 1930s and 1940s, says Anahi Alviso-Marino, a Paris-based academic and the leading specialist on the subject.

“It’s just not part of the official story of art in the region. This quarter of the world is quite invisible. That doesn’t mean that there are no artists or art practices or art history.”

Alviso-Marino, through her research, has documented how artist associations, societies, studios, and later, private galleries emerged during the later 20th century in Taiz, Sanaa, and Aden.

The painter Hashem Ali, for example, who died in 2009, ran his studio in Taiz during the 1970s and 1980s - the city held an exhibition and auction of his art in May 2019 to buy a home for his family.

During the same time the Association of Young Artists was active in Aden while the military museum in Sanaa housed Peace Guardians, a major painting by Abd al-Jabar Nu’man.

During the 1990s, the Yemeni culture and tourism office published a quarterly arts journal and the University of Hodeidah became the country’s first public university to offer a visual arts degree. Later, the Ministry of Culture set up houses of art to take exhibitions and workshops across the country.

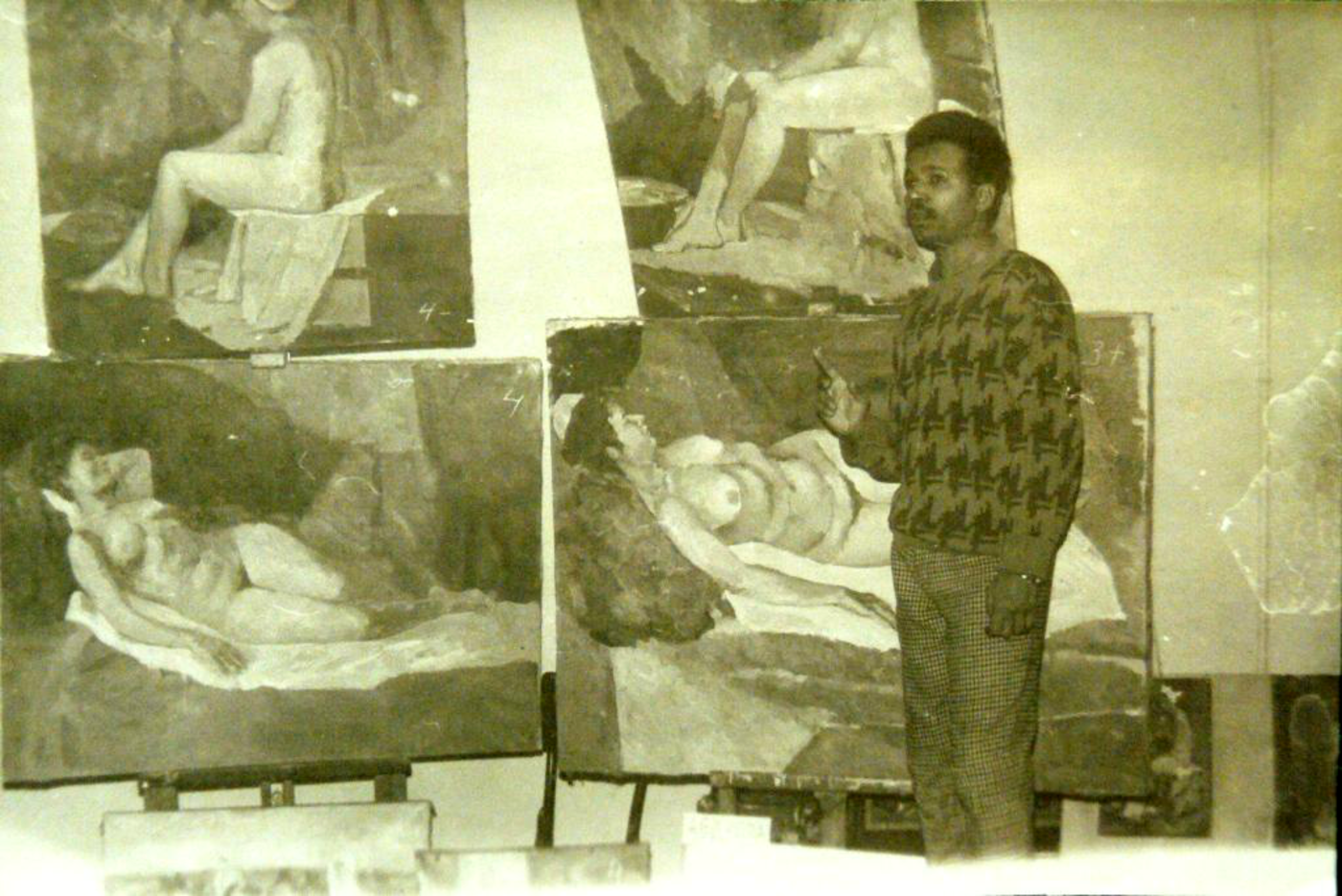

Art in Yemen was also open to overseas influence. Alviso-Marino has uncovered how, during the 1970s and 1980s, a scholarship programme took between 50 and 70 Yemeni painters, sculptors and poster artists to the Soviet Union to study fine arts as part of a Cold War cultural programme. Many spent years in Moscow for their master’s degrees, before returning to the Gulf.

The constraints and horror of the current war have resulted in a fresh wave of Yemeni artists who tend to be young - typically under 35 – and who are wary of being framed only within the context of the conflict.

They do not work in calligraphy or anything that could conventionally be called Islamic, or Middle Eastern art: instead, they often choose photography, film or new media. Many joined the 2011 protests in Sanaa’s Change Square, but do not want to be only defined as the product of just another war-torn country.

The output of this small but determined group, several of whom live and work overseas, has been celebrated across Europe, including exhibitions in Berlin in 2018 and Beirut earlier this year.

In early July the British Museum in London organised a symposium as part of the Shubbak Festival of Contemporary Arab Culture, highlighting the art of four artists (below) of Yemeni origin - a timely barometer of what is happening to the country's arts.

Visual artist: Salwa Aleryani

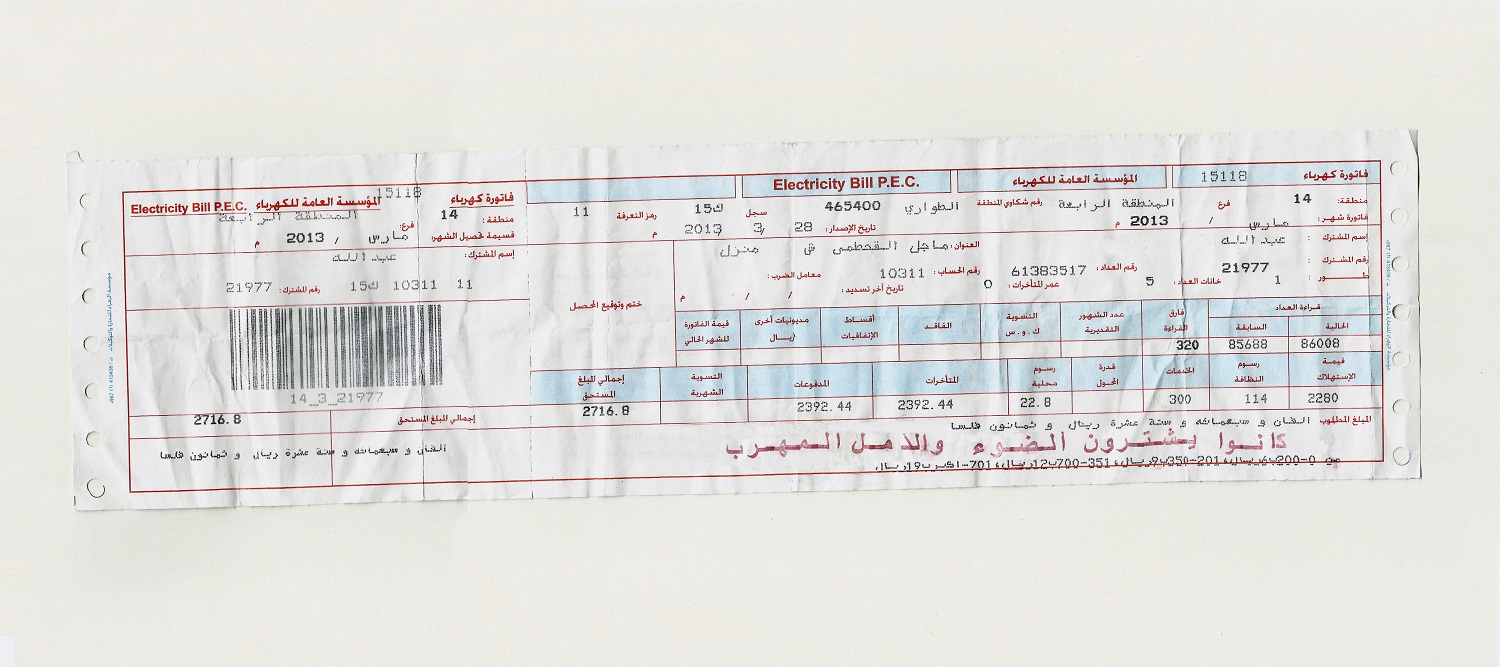

Salwa Aleryani, like millions of Yemenis, has seen the country’s regular power cuts worsen since 2012. Many of her fellow citizens have protested about the outages that can last up to 12 hours, but Aleryani was also inspired to create art. The electricity stopped flowing, she noticed, but the bills did not; nor even the demands for early payment.

For her project Where We Were When The Lights Went Out, she took utility bills and counter-stamped them with poetic lines in Arabic such as “A moment in the dark does not blind us” or “They purchased light and smuggled hope.” As a work of contemporary art, it is witty and bitterly ironic.

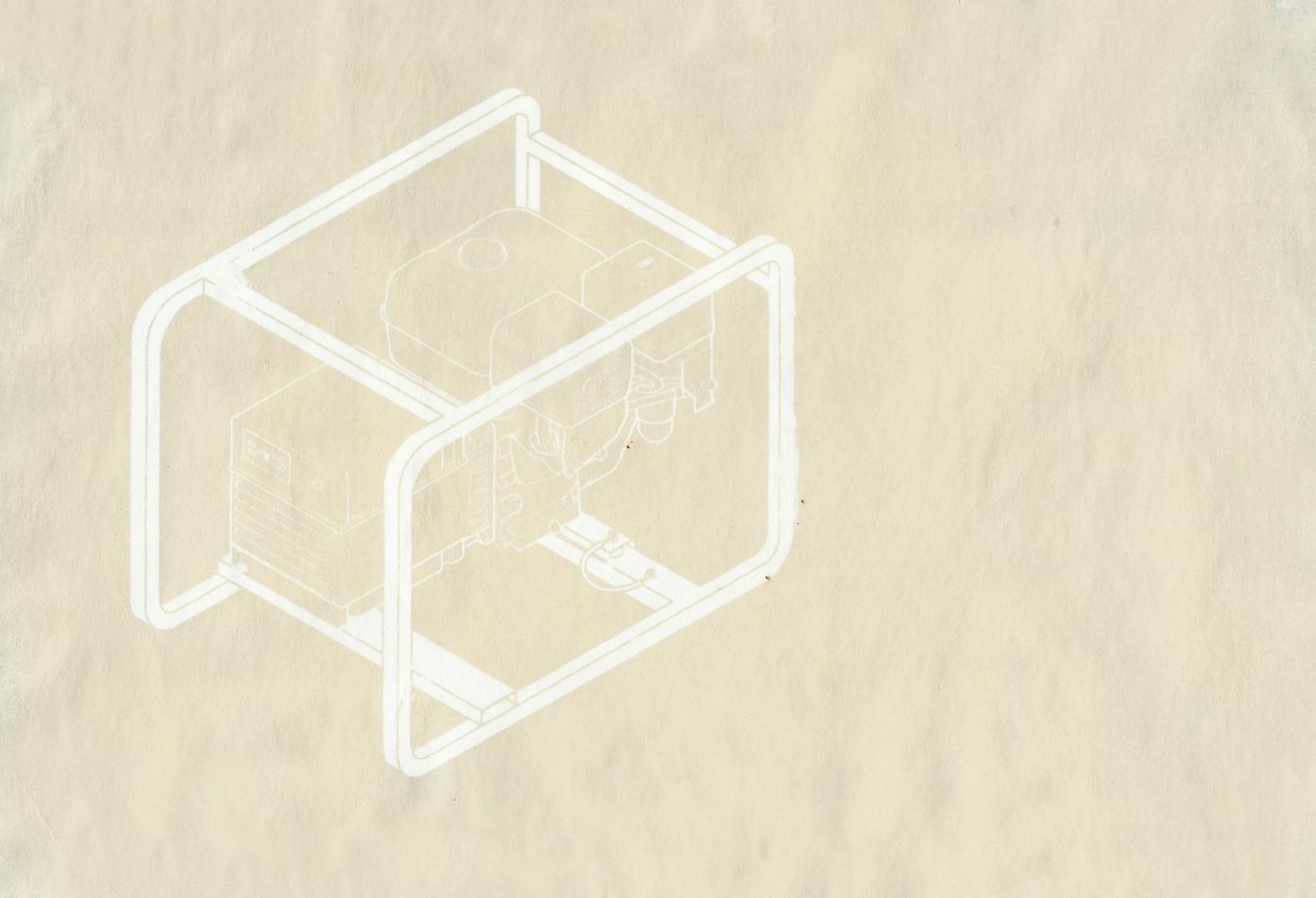

She also took a series of photographs, wryly observing how domestic electricity generators have become part of the furniture in local shops.

Aleryani trained in the United States after winning a prestigious Fullbright Scholarship. She has never displayed her electricity project but this year showed other abstract installations in Vienna, as well as at group shows in Istanbul and Berlin, where she is based.

Photography: Rahman Taha

Rahman Taha, who is based in Sanaa, has had his photography featured in The New Yorker and Forbes. He previously ran an art gallery in the Yemeni capital.

His films include Short Scenes Based On A True Story, an impressionistic view of life in Yemen. “It showed how you can make art in Yemen,” he says. “I tried to make it a commentary.

“I’m trying to understand Yemen the place and the people, and we have too many beautiful things in Yemen, even Yemeni people don’t know about this.”

Recent projects include Mr Ali, which explores Yemen through the eyes of a man of nearly 80, who has spent his life working on coffee plantations; and photographs of Yemenis watching the World Cup in Sanaa.

From Mountains To The Sea, another of Taha's works, reflects on Yemenis’ relationship with land and sea, including how residents migrate from the villages to the cities to secure well-paid work with militias.

In the coming months, he will be based in Cairo, ahead of an exhibition at the city’s much-respected Townhouse Gallery later this year.

“When you are inside the country, you have your own eyes,” he says of working in Yemen. “But when you move to another place, you change your opinion and think in a different way. This is important. The normal moments in life, it’s important too."

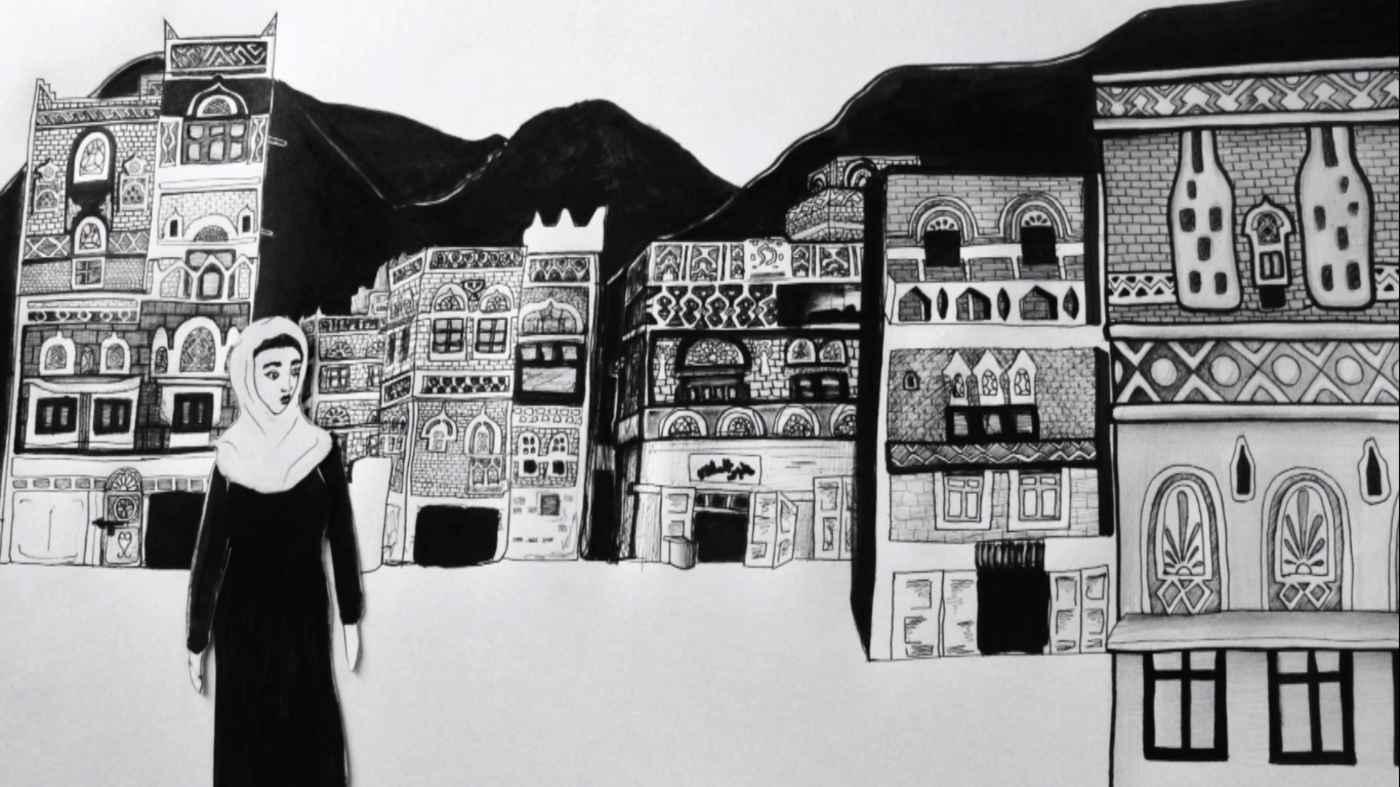

Visual arts: Ibi Ibrahim

Ibi Ibrahim is a visual artist and photographer based in Sanaa, whose wide-ranging work even includes dress design. He is the founder and director of the Romooz Foundation, an NGO which organised the recent exhibitions of contemporary Yemeni work in Berlin and Beirut, as well as more informal presentations in Sanaa.

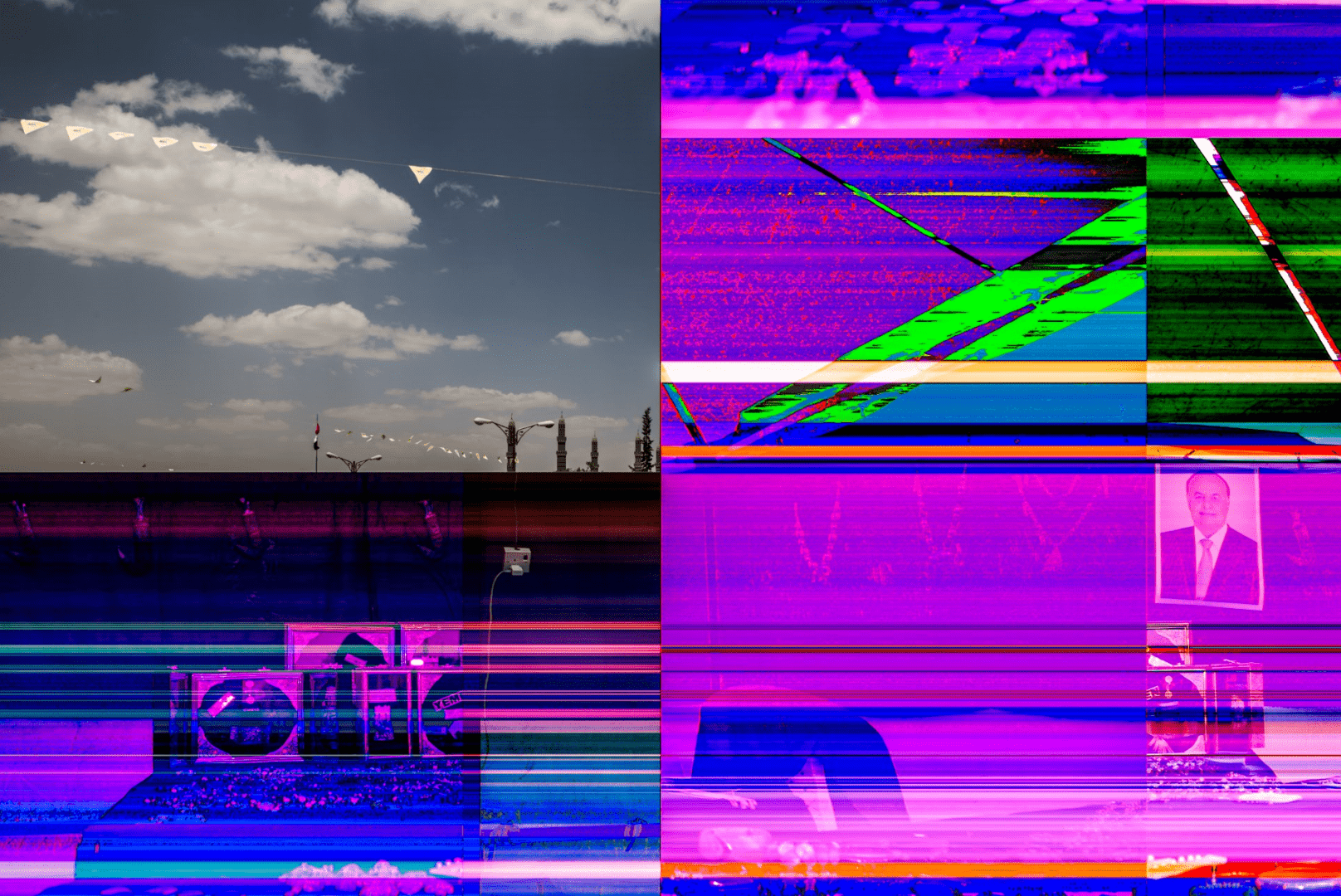

His exhibitions include artists like Arif al-Nomay, whose project The Corrupted Files consists of digital photographs taken in 2014 at Sanaa’s Summer Festival that were accidentally corrupted by his computer. The 60 images, shown as a grid installation, reveal what the catalogue described as “an ominous and eerie view” of the festival from days past.

Other work at the exhibitions has included collages, installations, neon art, and documentary photography. Artists in Yemen, Ibrahim says, paused only a few months when the conflict started. “When we realised the war was going to continue, we started making art.”

Street art: Murad Subay

Murad Subay from Sanaa is a self-taught street artist who is currently on a year-long scholarship in France. Although he is labelled by the media as “Yemen’s Banksy”, his work has yet to sell at Banksy prices.

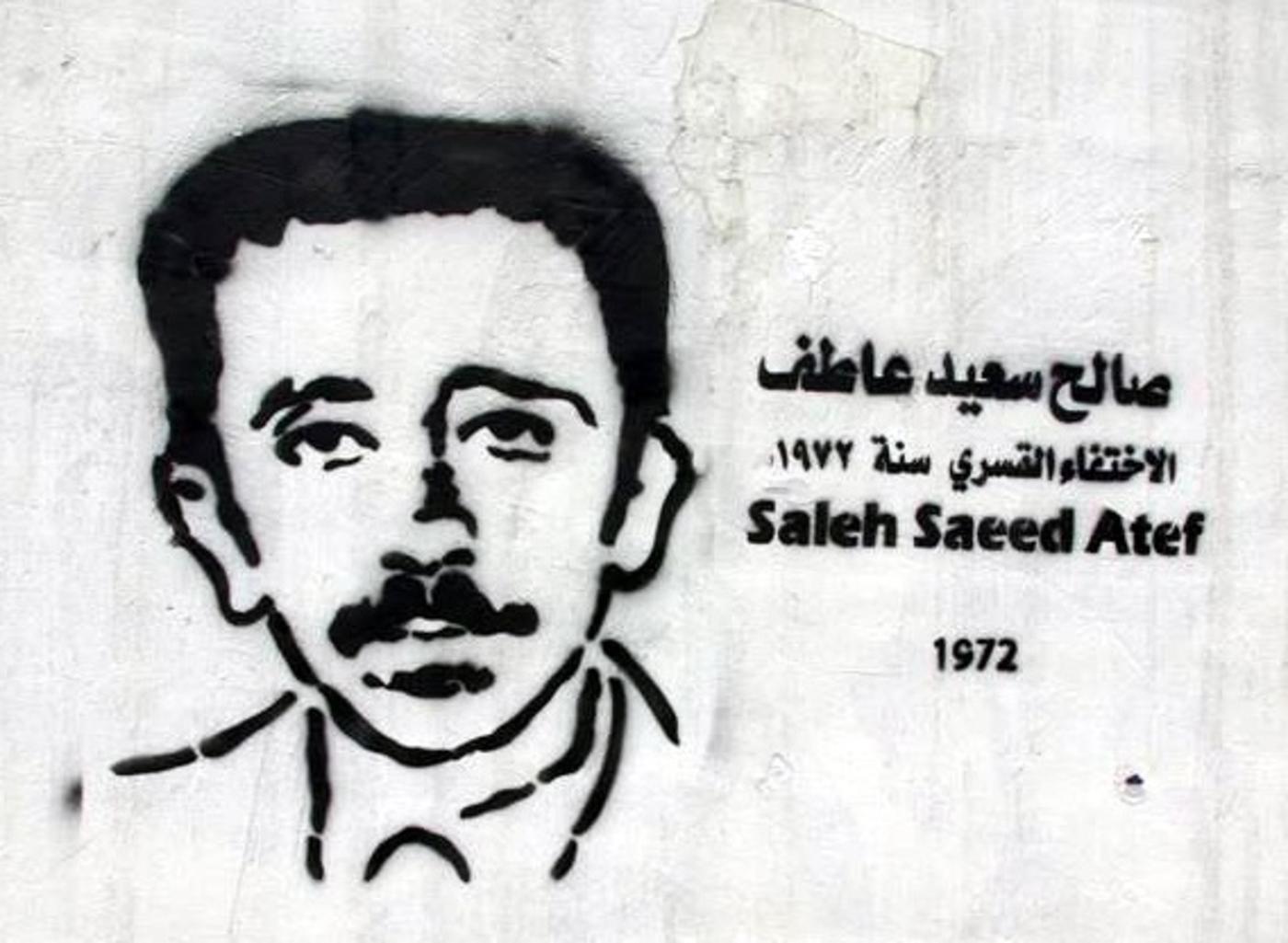

His first campaign, Colour The Walls Of Your Street, ran for three months in Yemen in 2012. Later that year, he created The Walls Remember their Faces, stencilling hundreds of faces across Sanaa and other cities in memory of the victims of “enforced disappearances”.

“The people are essential for this art scene, which is street art,” he says. “They were there with support, with participation because the unique thing about the street art in Yemen is that people are not the audience. They are participating by painting, by supporting, even by criticising.”

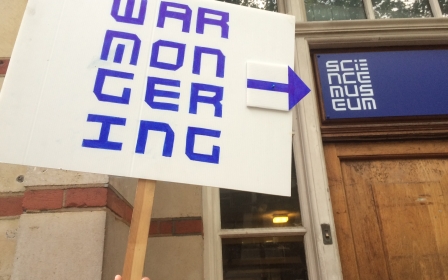

In the UK, Subay’s work is on display at the skateboard park on London's South Bank as part of a campaign against the arms trade, and at the Imperial War Museum in Manchester, where Devoured, a grim image of a skeletal figure being pecked by a crow, is part of the exhibition Yemen: Inside A Crisis.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.