Ergenekon: The bizarre case that shaped modern Turkey

In July, Turkey saw the closure of one of the longest-running and strangest chapters in its recent political history: the notorious Ergenekon trials.

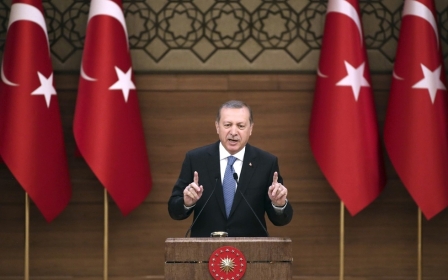

For decades prosecutors and police claimed a secretive, ultra-secular, ultra-nationalist organisation named Ergenekon had been carrying out terrorist attacks and manipulating events behind the scenes, all in an alleged plot to throw Turkey into chaos and justify a military coup ousting then-prime minister, and current President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

From the 1977 Taksim Square May Day massacre to the assassination of Armenian writer Hrant Dink in 2007, countless terror attacks and other destabilising events have been attributed to the shadowy organisation.

Since 2007, more than 500 people - including activists, journalists, military figures and politicians - have been arrested for their alleged connection to the group.

There was just one problem: Ergenekon may have never existed.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

On 1 July, the remaining 235 suspects in the case were acquitted of membership of a terrorist organisation - as an Istanbul court ruled that it could not decisively prove that Ergenekon was indeed real.

"It was understood that the existence of the Ergenekon armed terrorist organisation could not be proved by conclusive and convincing evidence, and therefore, leadership, membership and committing of crimes on behalf of the organisation could not be proved,” the Istanbul 4th Heavy Penal Court wrote in its ruling.

With the legal case coming to a close, questions remain over what began as a crackdown on ultra-nationalist and militarist elements in Turkey, but increasingly became viewed as a deliberate targeting of opponents of the powerful Gulenist movement and its erstwhile allies in the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP).

Today, the Gulen movement has itself become a pariah organisation. The Fethullahist Terror Organisation (FETO), as it is known to its opponents, has been subjected to a severe cracked down after it was blamed for the 15 July 2016 coup attempt against the AKP and its leader Erdogan.

But some argue that the fervent hunt for Ergenekon paradoxically played a role in normalising politically motivated arrests in the country.

A conspiracy theory is born

The existence of the “deep state” has long been a subject of debate in the country - but in the mid-1990s, one case blew the issue wide open in Turkey.

On 3 November 1996, a Mercedes Benz crashed into a truck on a road in the district of Susurluk, 145km south of Istanbul, killing three of its four passengers.

The three killed were Abdullah Catli, a wanted drugs smuggler and leader of a far-right paramilitary group known as the Grey Wolves; his girlfriend, model Gonca Uz; and Huseyin Kocadag, a former Istanbul deputy police chief. The only survivor of the accident was Sedat Bucak, an MP with the right-wing True Path Party.

Also in the car was a cache of weapons, drugs and a diplomatic passport owned by Catli that had been signed by the interior minister himself.

The crash exposed what many - particularly leftists and pro-Kurdish activists - had long suspected: that there were close, direct links between the military, the government, organised crime and ultra-nationalist paramilitary organisations such as the Grey Wolves.

Although numerous arrests and resignations took place after the Susurluk scandal broke out, ultimately no one was sentenced - in large part due to the army and intelligence services’ refusal to cooperate.

In the wake of the case, former prime minister Bulent Ecevit told Turkish parliament in 1996 that he had learned of the existence of a CIA-backed “stay-behind” operation within the Turkish military in the 1970s, tasked with targeting potential threats from communists and other left-wing groups.

"The same story you see in Pinochet's Chile, Videla's Argentina - you see it in Turkey, too," Selim Sazak, a doctoral student in political science at Brown University, told Middle East Eye. "It was a repertoire of the anti-Communist struggle the US was waging."

While Ecevit is the first major figure to have brought up the likelihood of a foreign-backed armed group, it was only the following year that the name “Ergenekon” emerged in this context.

Ergenekon refers to a place in Turkic mythology, supposedly in the Altai mountains in central Asia. According to the myth, Ergenekon was a valley where ancient Turks took refuge after a military defeat, before being led to freedom and greater glory four centuries later by the grey wolf Asena.

In 1997, former naval officer turned TV presenter Erol Mutercimler announced during a televised programme that he had been informed by a retired general of the existence of an organisation called Ergenekon, allegedly created by the CIA in the wake of the 1960 coup.

Mutercimler, already known as somewhat of a conspiracy theorist, said the organisation involved a wide network of right-wing journalists, academics, police and military figures, and was behind numerous unexplained murders in the country’s Kurdish region.

He called on the government to investigate and expose the deep state and its activities.

“We have a debt to the little children of this country, I mean to our children and grandchildren - and that is to deliver a clean country [to them],” he told journalist Can Dundar on a TV show in 1997.

Mutercimler would himself later be arrested in 2008 over his alleged connections to Ergenekon.

It would take another decade before the mysterious Ergenekon would become the focus of a full-fledged legal investigation - but the Susurluk scandal paved the way for the idea of a murky deep-state organisation to take root in Turkish consciousness.

A weapons stash snowballs into a crackdown

As the country geared up for presidential elections that would see Abdullah Gul become Turkey’s first president with an Islamist background in August 2007, an e-memorandum issued by the military in April threatened to intervene to “protect the unchangeable characteristics of the Republic of Turkey”, a statement widely perceived as a threat against a potential Gul presidency.

It was in a strained pre-electoral atmosphere that police raided the home of a muhtar - an elected village head - in the working-class district of Umraniye in Istanbul on 12 June 2007, following an anonymous tip-off over a cache of weapons, including grenades and C4 explosives.

The building’s owner, Mehmet Demirtass, and his nephew were both arrested - and following statements from the two, police also subsequently arrested a retired officer, Oktay Yildirim, and a retired army major, Muzaffer Tekin.

More arrests would follow, almost entirely consisting of former military officials and ultra-nationalists, all accused of belonging to Ergenekon.

Leading the hunt against Ergenekon - both at the law and order level and in the media - were supporters of prominent exiled cleric Fethullah Gulen.

In the 2000s up until 2013, Gulen was aligned with the ruling conservative AKP for both tactical and ideological reasons. The cleric’s various affiliated institutions were at one point thought to be worth as much as $50bn worldwide and the form of Islam he promoted - ostensibly tolerant, in favour of secular governance and pro-Western - helped him and his followers establish deep roots in Washington foreign policy and lobbying circles.

Oversight of the Umraniye weapons stash case was handed to public prosecutor Zekeriya Oz, a well-known Gulenist, who became the public face of the investigation and prosecution of Ergenekon suspects.

Meanwhile, articles in pro-government and Gulenist outlets began to report that the grenades found in the raid were linked to grenades used in an attack on the office of secular-nationalist newspaper Cumhuriyet in 2006.

Gareth Jenkins, a non-resident senior research fellow with the Joint Center's Silk Road Studies Program and one of the few early foreign critics of the Ergenekon trials, derisively commented in 2009 about media reports suggesting grenades from the same stash had been used in a wide array of attacks dating back to 1999 - “as if a vast organisation, which by early 2008 was being characterised by the pro-AKP media as being responsible for virtually every act of political violence over the previous 20 years, was working its way through a single crate of grenades”.

Massive republican protests in April and May 2007 against Gul’s ascendency to the presidency further emboldened those who felt the traditionally secularist army and its supporters needed their wings clipped.

In the year following the Umraniye raid, scores of people - including high-profile ultra-nationalist figures like lawyer Kemal Kerincsiz and Turkish Orthodox Church spokesman Sevgi Erenerol - were detained over their alleged ties to Ergenekon.

But some of those arrested did not necessarily fit into the ultra-nationalist secularist views that supposedly guided the shadowy organisation.

In 2008, those arrested included newspaper editor Ilhan Selcuk - whose very publication Cumhuriyet had been allegedly targeted by Ergenekon - and Mutercimler, the man who first publicly spoke about the group.

The contradictions and gaps in the Ergenekon file soon became more glaring.

Wild hypotheses and planted evidence

The first indictment in the Ergenekon cases, prepared in July 2008, was 2,455 pages long and formally charged 86 people with offences such as “membership of an armed terrorist organisation”, “encouraging the military to insubordination” and “attempting to overthrow the government of the Turkish Republic by using violence and coercion”.

The majority of the evidence listed in the indictment was gleaned from one source: former journalist Tuncay Guney, who was arrested in 2001 and found to have in his possession various documents referring to Ergenekon and individuals who were later arrested. The rest of the evidence in the case was largely drawn from a combination of wiretaps and documents found in suspects’ homes.

Guney’s interrogation would form the backbone of the Ergenekon trials - but Guney was an unreliable figure. The man was described by Jenkins as “a self-important but intellectually challenged fantasist”, and Guney’s lawyer told media in 2008 that “90 percent of his claims relate to a world he has created himself”.

The indictment was criticised for being clumsily worded, full of grammar and spelling mistakes, and indulging in conspiratorial language - describing Ergenekon as modelled on the “Masonic Bilderberg organisation, German Nazi organisation, British Intelligence front organisations”, among other sources of inspiration.

Another section said the alleged Ergenekon conspirators had plans to “manufacture chemical and biological weapons” and to “finance and control every terrorist organisation, not just in Turkey but in the entire world”.

In 2014, the chief judge in the trial conceded that he had not actually fully read the initial indictment when it was first unveiled. But despite the questions raised by the 2008 document, subsequent indictments were submitted in March and August 2009, and a further 21 were issued up until 2013.

The later waves of arrests saw more and more journalists put behind bars - including OdaTV founder Soner Yalcin and editor-in-chief Baris Pehlivan in February 2011.

A report released by digital forensics group Arsenal Consulting in 2016 revealed that documents found on Pehlivan's computer purportedly proving OdaTV's links to Ergenekon had in fact been planted with, an Arsenal Consulting analyst believed, a “very specific agenda” in mind.

Pehlivan spent 19 months in total in jail, before being released in September 2012 - but it would be 2017 before he was fully acquitted, with help from the Arsenal Consulting report.

His experience made him realise the influence that journalists could wield.

"Prison was a school for me," he told MEE. "It made me look for the truth more enthusiastically and believe more in the power of the pen."

Liberal and Western support

Despite the absurdity of some of the cases, many people in Turkey and abroad backed the trials, not just supporters of the Gulen movement leading the charge against Ergenekon.

Even if they did not believe that Ergenekon was responsible for everything it was accused of, many leftists and liberals saw the trials as an opportunity to see people who had undermined the democratic process and sponsored extrajudicial killings be brought to justice.

Abdullah Bozkurt - a former writer for the English-language edition of Gulen-aligned Zaman newspaper, Today’s Zaman - maintains that the investigation was “justified at its core” and that the trials were only undermined once they became “politicised”.

“Many in Turkey and abroad, including the European Union, thought trials offered an opportunity for further democratisation in Turkey,” he told MEE.

Throughout its history, Turkey has undergone a number of military coups, decimating Turkey’s once-powerful left-wing socialist and Communist groups in the process.

Within this context, support for the Ergenekon trials was forthcoming from many liberal intellectuals - even those who were not natural allies of either the Gulen movement or the AKP - who wanted retribution for the army's repeated crushing of progressive movements.

A group of 300 left-wing and liberal intellectuals, journalists and academics signed a letter in August 2008 proclaiming their support for the Ergenekon investigations, calling for it to go even further and “deeper”.

Writing in the Guardian in 2008, Bulent Kenes - a journalist with Zaman - said routing out Ergenekon was “a vital test for Turkish democracy.”

“Thanks to this trial, for the first time in its history, Turkey is attempting to try military officers on active duty on charges of attempting to overthrow the elected government,” wrote Kenes, who would later go to jail for “insulting” Erdogan.

“If it can do this successfully, Turkish democracy has a bright future.”

At the time, many in the West were still touting “the Turkish model” - a supposed combination of moderate Islamism, liberal democracy, and free markets - as an example for the “Muslim world”.

In 2010, a European Commission report called the Ergenekon trials “an opportunity for Turkey to strengthen confidence in the proper functioning of its democratic institutions and the rule of law” - although it did note that there were “concerns” regarding “judicial guarantees for all suspects”.

Human rights organisations such as Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, meanwhile, argued that the trials had not gone far enough.

But the breadth and scope of those arrested eventually stretched far beyond the ultra-nationalist and secularist establishment. Soon, it became apparent that those being targeted were often simply enemies of the Gulenists and the AKP.

“Many foreign media outlets and politicians partnered with this lie - on purpose or not,” Pehlivan told MEE. “They were absolutely wrong. It was a trick.”

For Sazak, the silence or complicity of many in the US and Europe sowed a serious level of mistrust between people who had been anti-Erdogan - and whose lifestyles and values were often branded as “Western” - and the West.

The result was a form of “trauma” which later crystallised in a “Eurasianist” push from many of those targeted by the trials, calling for closer ties with Russia and China and a split from NATO and the EU, he said, arguing that the repercussions of this were still strongly felt today.

“When the gallows were being set and the hangman was lining up, the West was cheering on the sidelines,” said Sazak.

‘If you touch him, you will burn’

While praise for the Ergenekon trials piled on, many observers had issues about the nature of the arrests, but were wary of speaking out when those thrown in prison often happened to be controversial and morally suspect figures.

This changed, however, with the arrests of Nedim Sener and Ahmet Sik in March 2011.

Both Sener and Sik were well known journalists - and outspoken critics of the Gulenist movement.

“I have seen the FETO structure, which can be compared to a table consisting of four legs, where the police, prosecutors, judges and journalists come together,” Sener told MEE, using the derogatory acronym used by opponents to refer to Gulen’s organisation.

In 2009, Sener wrote a book accusing Gulen elements in the police of being complicit in the murder of Armenian journalist Hrant Dink - a death which had been blamed on Ergenekon.

"While I was doing all this, I didn't think they would put me in the Ergenekon investigation they were conducting," he said. "I've lived with their evil impacting my freedom and my life...After being arrested and imprisoned, I saw that this [Gulenist] organisation could do even greater evils to everyone."

Sik, meanwhile, had previously faced prosecution for a 2007 article which called for the army to stay out of politics. By 2011, however, he was working on a book called The Imam’s Army, aiming to detail the ties between the Gulen movement and the police, casting doubts on the independence of the institution and - by implication - the Ergenekon arrests.

Bozkurt, the Today’s Zaman journalist, claimed The Imam’s Army was “written with the explicit directions and support of the Ergenekon terrorist gang for the purpose of derailing the case or at least making it look flawed in the eyes of the public”.

The manuscript was seized and shortly afterwards, Sik and Sener were both thrown in jail and charged with belonging to Ergenekon.

As he was being led away by police, Sik reportedly shouted in reference to Gulen: “If you touch him, you will burn!”

Although the book was banned in Turkey, Sik's manuscript was uploaded to the internet in April 2011, where it was downloaded hundreds of thousands of times, while NGOs and politicians both in Turkey and abroad condemned the arrests as politically motivated.

In November that same year, a version of the Imam's Army was published under the title 000Kitap - meaning “book” in Turkish - with editorial contributions from 125 writers.

“000Kitap is the product of collective efforts by those who insist on freedom of expression and freedom of information rights, despite all oppression, obstruction and bullying,” the publishers wrote in a press statement.

The backlash following Sik and Sener’s arrests saw Oz appointed deputy public chief prosecutor of Istanbul, effectively stripping him of his decision-making powers in the Ergenekon trials.

Pehlivan said that the blatant absurdity of the Sener, Sik and OdaTV arrests was a “breaking point” in the public’s attitude to the Ergenekon file.

“We caused the broader public to question whether these cases had an agenda behind the scenes,” he said.

Sener and Sik both spent a year in prison. In a speech made shortly after his release in 2012, Sik called out the country’s leadership for its responsibility in the journalists’ detention.

“The culprits of this affair are figures in the bureaucracy and the police connected to the [Gulen] community, and the true culprit is the government of the AKP who keeps silent in the face of all this,” he said.

Shortly afterwards, Sik would be indicted for making that speech. In December 2016, in perhaps the most bizarre and ironic twist yet, Sik would once again be imprisoned - this time over allegations of being a propagandist for the Gulen movement.

The tables turn

With the Ergenekon trials’ image already seriously tarnished by 2011, the spectacular falling out between the AKP and the Gulen movement in 2013 brought them to an abrupt halt.

The erstwhile allies, who had once found common ground opposing both the military and the secular ancien regime, came to blows over a number of issues, mostly derived from a mutual fear that each party was attempting to monopolise power.

In December 2013, prosecutors launched a wide-ranging corruption investigation into Erdogan and his closest allies. In turn, Erdogan and the AKP accused the Gulen movement of attempting to launch a judicial “coup” against the government.

In the wake of a coup attempt on 15 July 2016, which Gulen was accused of fomenting, thousands of police officers, civil servants and others accused of links to the Gulen movement - including prosecutors involved in the Ergenekon trials - were sacked and arrested.

Zaman, the popular Gulen-affiliated newspaper that used to openly root for the crackdown on Ergenekon, was effectively taken over by the government after its offices were raided.

Journalists who had hailed the hunt for Ergenekon affiliates as a vital test for Turkish democracy, were now ending up in prison over their alleged involvement with the Gulenist movement.

Oz, the Gulenist prosecutor formerly in charge of the Ergenekon file, fled Turkey after a warrant was issued for his arrest in 2015.

The anti-Gulen crackdown has provoked outcry from human rights organisations and foreign governments - but for the original targets of the Ergenekon investigations, Gulen supporters have merely been given a taste of their own medicine.

“I say it’s God’s justice,” Sener said. “They are now on trial for their own false accusations.”

“I never thought I'd see this result. I think that this is God's justice against those who do evil. There was no Ergenekon terrorist organisation - but there was a Fethullahist terrorist organisation.”

Hundreds of sentences were handed down to Ergenekon suspects in 2013 - but in the wake of the AKP/Gulen fallout, many of them were overturned within a year.

In April 2016, Turkey’s highest appeals court overturned the convictions of 275 people involved in the case - and on 1 July, 235 more were acquitted as it was officially ruled that Ergenekon’s existence could not be proven.

Meanwhile, the vacuum left by the mass purge of Gulenists from the military and government has meant that many officials once accused of involvement in Ergenekon have since returned to their roles.

For Bozkurt, the acquittals stand as proof that Erdogan is now thoroughly embedded with Ergenekon - an organisation which the journalist maintains is very real.

“The recent acquittal decision is nothing but a whitewashing of Ergenekon’s crimes in exchange for sustaining the regime of Erdogan in the face of mounting difficulties,” he argued.

A bitter legacy

But while the slate has been officially wiped clean for those accused of belonging to Ergenekon, bitterness still remains - not least for those who died or committed suicide while in prison.

“Will the dead come back? Many people lost their lives,” the wife of Kuddusi Okkir, a businessman who succumbed to cancer in prison in 2008, asked in 2016 in response to convictions being overturned.

For Sazak, one of the biggest consequences of the Ergenekon affair has been that the trials’ farcical nature and overt politicisation meant many people who should have faced justice for very real crimes never did.

“They need to be brought to justice the same way that high-ranking Gulenists and their AKP associates need to be brought to justice,” he said. “It’s necessary for Turkey’s democratic normalisation - and we had that opportunity.”

The Susurluk scandal that started it all was a “democratic milestone”, Sazak said - and “had Erdogan and Gulen not abused it for their own benefits, [the Ergenekon trials] would have been a second democratic milestone”.

“And that is inexcusable.”

For Pehlivan, the Ergenekon trials laid the groundwork for Turkey’s human rights failings today - not least in its reputation as the "world's worst jailer" of journalists.

"If you are experiencing a hunger for justice in Turkey today, if you are experiencing a press freedom problem in Turkey today […] what happened in the process of those cases carries a large share of the responsibility," he said.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.