Israel's left lost a million votes in the last polls. Here's how they get them back

Immediately after he was elected as chairman of the Labor Party in July, Amir Peretz decided on a change of direction.

For decades, the Labor party has been the dominant force in the Israeli centre-left. In the April elections, it shrank to six seats, its lowest result ever. So Peretz was expected to align with Meretz to rehabilitate the party.

Without the periphery, Likud would not have been the largest party and the right wing would not have had a legislative majority

Instead, he teamed up with Orly Levy, a former member of the right wing Yisrael Beiteinu party, headed by Avigdor Lieberman. Levy led her own party, Gesher, in the April polls, but failed to pass the threshold to enter the Knesset.

Peretz has said that the alliance is intended to reach out to Israel’s social periphery, urban areas outside of the Tel Aviv area that have Mizrahi majorities – Israeli Jews whose roots are from Arab countries – and who also have relatively low incomes.

Their pairing evoked an outcry on the left. Many people argued that Peretz made the move as a wink at the right and in an effort to join Netanyahu's government, which Peretz vehemently denies.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Others questioned the logic behind the step. People in the periphery don’t vote leftist, they said, so better to concentrate on getting out the vote in well-to-do communities in the centre of the country that already vote for Labor and Meretz.

In fact, this is exactly why the alliance could be a turning point. The Labor party, like the Jewish left in general, has long been identified with the Ashkenazim - Israeli Jews of European or Western descent – who are placed higher in the socio-economic echelon in Israel; the same with Meretz voters.

Both Levy and Peretz are Mizrahi Jews of Moroccan descent who live in marginalised areas and may therefore have a chance to pick up votes in these areas, long ago abandoned by the left, which were decisive in the last election.

The power of the periphery

The notion of “periphery” is of course quite flexible. In the greater Tel Aviv area, there are many neighbourhoods that could be considered peripheral if the yardstick is socio-economic or ethnic. The same is true for Jerusalem and Haifa and areas around it.

But for the purposes of gauging the power of the periphery in the last election, I have looked at central election committee data on urban communities outside of greater Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Haifa and its surroundings, which have a large population of Mizrahi or Russian Jews and also are almost exclusively at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics.

While there are big differences between the various communities, residents tend to share a relatively clear consciousness of belonging to marginalised areas. At least, that was my experience as a journalist, interviewing many from the Jewish periphery over several decades. Arab towns in Israel are also part of the periphery, but theirs is a different story.

Here's what I found:

Out of the 37 urban locations that I focused on, just over a million people voted out of the 1.6 million who were eligible. That’s a 62.5 percent voter turnout, below the national average. The votes of those who went to the polls were worth about 30 legislative seats, a quarter of the Knesset total.

The two leftist parties, Labor and Meretz, garnered 3.25 percent of the vote, worth a single seat. In other words, these two historic parties which view themselves as national parties simply don’t exist on the periphery; nothing left there.

About 16.8 percent of voters on the periphery, or about 170,000 people, voted Blue and White, which was worth a bit more than five Knesset seats for that party. Another 60,000 votes, some 5.9 percent worth about 1.8 seats, went to Gesher and Kulanu, both Mizrahi/social welfare-oriented parties. Another half a seat, about 13,400 votes, went to Hadash-Taal and Raam-Balad, (mostly) Arab parties in the mixed cities of Lod, Ramle, Upper Nazareth and Acre.

Nearly all of the 22 remaining seats went to parties of the right. The Likud won most of them: nearly 390,000 votes, 38.7 percent, worth nearly 12 seats for the Likud; a third of its voters. In short, without the periphery, Likud would not have been the largest party in Israel and the right wing would not have had a legislative majority; very straightforward.

No last minute fixes

It’s not clear how the left can call itself the left and yet give up in advance on more than a million voters. What’s leftist about giving up in advance on the poorer, weaker, and most marginalised voters?

“It’s criminal negligence, the way the left makes matters worse," said Avi Dabush, who ran for the chairmanship of Meretz and headed the party’s caucus for the periphery. Today, he is the CEO of the nonprofit Rabbis for Human Rights.

'It’s criminal negligence, the way the left makes matters worse'

- Avi Dabush, former Meretz chairman

There are no shortcuts, said Dabush. The left needs the periphery because there’s no chance for a victory without it. The work in the periphery, Dabush argued, must happen all year round, every year: “You can’t just show up at the last minute.”

Precisely because he also lives in Sderot, Dabush is aware that right wing governments “give a lot of gifts” to the periphery such as discounts on summer pool memberships, cheap movie tickets, and subsidised preschools.

Weighed against these “gifts”, Dabush said, it is impossible to satisfy voters with homilies about “social justice”. If you want votes, he argued, then “you have to say what you’re giving in exchange". But right now, he added, the left really has nothing to offer in place of the Likud’s “gifts” and has little interest in poverty.

Dabush is not at all surprised by the very low voter turnout for left wing parties in periphery towns. In his own experience, these voters are quite likely Ashkenazim or come from a somewhat higher socioeconomic class.

A few days ago, he said, he met with a group of young people. One of them from Ofakim, a city in southern Israel, told him that “he had never heard of anyone from Ofakim voting left".

The young man was not far off: only 215 people in Ofakim voted for Labor and Meretz - or 1.5 percent of the city's votes. In nearby Netivot, another southern city, only 0.6 percent of the population - or 110 voters - supported the left. In Sderot where Peretz lives, Labor received only 3.8 percent, according to the Central Election Committee.

There were only three locations out of 37 in which the proportion of voters for the left exceeded five percent.

How we got here

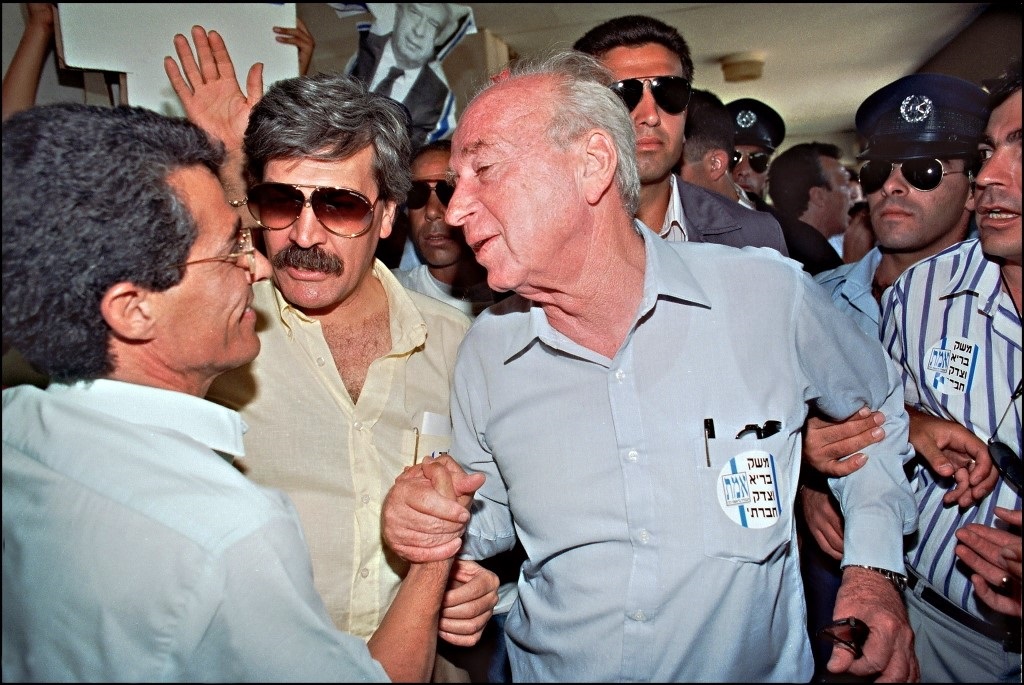

So how did these two left wing parties – Labor and Meretz – which got 56 seats in the Knesset when Yitzhak Rabin was elected prime minister in 1992, reach such a lamentable result, especially in these Mizrahi-dominated towns outside of Tel Aviv?

Hani Zubeida, chair of the political science department at Jezreel Valley College, said the General Federation of Workers in Israel, known as the Histadrut, used to be the "arm of the left in the periphery", providing jobs.

But in 1985, the body, perceived as old and burdensome, was dismantled in an attempt to renew the Labor party. No one remained to do the outreach for the left, Zubeida said.

Revital Amiran, an expert in political science and a columnist for the Hebrew-language Israeli daily Maariv, said that since the late 1970s, the Israeli left has had nothing to offer to the periphery.

“After the old-timers who established the state had benefited from state social welfare and attained economic security, they stopped supporting the welfare state and began supporting a free market. The social-democratic story wore very thin," she said.

Nonetheless, said Zubeida, conceding a million voters is just not an option. “A real left has to offer free medicines, it has to offer free swimming pools,” he said, as a response to the “gifts” that the right offers to the periphery. "It has to offer free nursing care.”

It should also offer land redistribution as the small towns where Mizrahi Jews live are heavily inferior in this respect compared with the surrounding kibbutzim, historically identified with the Labor party.

According to research conducted by Zubeida's students, life expectancy in peripheral towns in the north is 11 years less than for kibbutz residents in the same area. "The question is not the periphery,” he said. “It’s about who is excluded.”

Identity politics

Labor-Gesher's economic platform, announced earlier this month, goes some way to make offerings to those who have been excluded.

It calls for raising the minimum wage, 200,000 new government-constructed apartments, state-provided nursing care, free education from birth onward, higher state pensions, and not least – raising income taxes on the highest earners.

The work on identity, said Amiran, is no less important. “The left tends to see ‘identity politics’ as something negative,” she said, but in her opinion, that is a mistake. Rather, it is the source of the rift with “the Mizrahi left”, as she puts it.

“They have to respect people’s cultural identity in order to forge a partnership,” she said. “Israel is a traditional state. A social democracy cannot leave this aspect out.”

And beyond all these questions, there is also the question of representation. “Why should you vote for someone who isn’t from your community,” Dabush mused.

From that standpoint, said Zubeida, Peretz is doing something very important. He himself is positioning Levy to head a leadership that is clearly Mizrahi and from the periphery: “He says: Let’s say that we are the periphery, let’s say that we are Mizrahim, let’s try to reach that one million.”

Zubeida does not expect that Peretz and Levy will persuade a great many of those one million voters from the periphery to move in their direction, yet he also leaves room for a surprise.

Amiran is more sceptical. She thinks that what Peretz and Levy are doing is “laudable, appropriate and necessary” but also thinks it has come too late. “You can’t alter people’s consciousness after so many years in just a month or two," she said.

But Amiran and Zubeida agree that if Labor-Gesher can exceed the electoral threshold in September and do well, it could certainly become the basis for new action by the left in the periphery.

And even if Peretz’s choice of an alliance with Levy had petty political motives, as claimed by some of its critics, what seems certain is that a million voters in the periphery have now become players in the calculations of the left. That, too, is a welcome change.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.