Marriage, materialism, and the macabre: Meet Kuwait's new generation of artists

Visual art in Kuwait has come a long way since 1936, when the first art scholarships were granted in the country and art became a subject in primary schools.

Today the young oil-rich nation, suspended between modernity and tradition, is home to a new generation of artists, experimenting with innovative forms.

The country's first art exhibition was held in 1943 and saw the participation of the country's first visual artist and pioneer of portraiture, Mojib al-Dousari (1921-1956). And in 1969, Kuwaiti siblings Najat and Ghazi Sultan established the Sultan Gallery in Kuwait City, the first Arab art space in the Gulf.

It was around this time that the country saw the rise of its own homegrown art movement named Circulism - an art form relying on circular and curved lines based on philosophy, spirituality and science - created by Kuwaiti artist Khalifa al-Qattan (1934-2003).

Initially influenced by Cubism, he went on to develop his own art style with the support of his wife, Italian-born writer and artist Lidia al-Qattan.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Today, Kuwait boasts a number of prominent artists, like Thuraya al-Baqsami, Sami Mohammed and Shurooq Amin. While Baqsami, one of the first female artists and writers of the region, and sculptor Mohammed, are considered pioneers of the modern art movement in the Gulf, Amin was the first female Kuwaiti artist to exhibit at the Venice Biennale in 2015 and to have her works auctioned at London auctioneer, Christie’s.

The past decade has also seen a new wave of talent bring dynamism and diversity to the art scene. Most of these younger artists are self-taught, pursuing their education in other fields such as architecture, design or engineering because of limited access to specialist cultural institutions. Though these institutions exist, says artist Aseel AlYaqoub, they are “inconsistent, bureaucratic, limited and conservative”.

Yet with the help of digital developments and social media, this new generation too have found their audience.

1. Aseel AlYaqoub

One of the 2018 winners of the first Art Jameel Commission, a non-profit that supports and commissions art in the Middle East, Aseel AlYaqoub's work has been featured in exhibitions in New York, London, Budapest and Kuwait.

Avidly drawing since she was six years old, AlYaqoub studied in the UK and New York, then in her 30s, she moved to London in 2016 to make a living as a professional artist. “I was consistently pigeon-holed as a female Arab artist in the diaspora. I found this detrimental and decided to move back to Kuwait… to genuinely develop my work on the ground, rather than from a top-down perspective.”

Much of AlYaqoub's art focuses on Kuwait’s chronicle as a nation-state. By using nostalgia as a critical tool, AlYaqoub explores Kuwait’s collective memory and its past, contextualising it into the present in a satirical and inquisitive way.

She says she hopes to make people “question the nation as a community of people who are connected to each other without knowing each other, unfamiliar with each other's beliefs or traditions”.

As her drawing, installation, video and printmaking works rely heavily on academic history and politics, she says she found it challenging to translate this into something visually simplified, whilst balancing “a sense of light-heartedness, wit and humour”.

In what she defines as one of her most underrated works, Frenemies (2017), AlYaqoub stages a WhatsApp group conversation set in 1920, during the Kuwait-Najd War period when Ibn Saud, the ruler of Najd - a region in central Saudi Arabia - wanted to annex Kuwait to his sultanate.

The Whatsapp exchange, sourced from old telegrams, letters and notes found on the Qatar Digital Library, takes place between British political agents and Gulf rulers of that time and leads to a dispute between Ibn Saud, the first monarch and founder of Saudi Arabia, and the ruler of Kuwait, Sheikh Salem al-Sabah, over the two countries' boundary.

In the Battle of Jahra (1920), a Saudi supported militia (the Ikhwan) attacks The Red Fort in Kuwait – this historic battle initiated Britain’s move to draw up state boundaries between Kuwait and Najd.

Presented as a video projection, the piece was shown at the French Institute of Kuwait and is now available online. "It's fascinating how a red pencil, and one man, can draw arbitrary lines on a piece of paper that then literally extrudes reality into borders,” AlYaqoub says.

2. Mohammed Al-Hemd

Born and raised in Kuwait, experimental artist Mohammad Al-Hemd, 40, has a background in engineering and graphic design, which served as his gateway into art.

“Art was intimidating for me in the beginning as I was getting harsh critiques from art teachers throughout my education,” Al-Hemd says. “After breaking my fear by creating non-mainstream designs, I started to create artworks in 2014 as a response to the political events and tension mounting in the region [following the so-called Arab Spring].”

Featured at various regional exhibitions such as Reinterpreting Contemporary in Saudi Arabia (2015) and among the winners of the Arte Laguna Prize 2019/20, one of the world’s most influential competitions for emerging artists, Al-Hemd typically uses installations and different types of media, from wood, metal, mirrors to photography and videography.

The main themes connecting his work are what he perceives to be the social taboos and the injustices of the Arab and Muslim world. He tackles themes such as terrorism, censorship, the Syrian refugee crisis and rape crimes.

In his video installation Article 182 Marriage, displayed at a collective exhibit at Kuwait's The Hub gallery in 2018, he sheds light on an article of the Kuwaiti Penal Law, no. 16 of 1960, which is often manipulated by rapists and kidnappers to escape punishment by marrying their victims.

According to a 2019 HRW report, the law “allows an abductor who uses force, threat or deception with the intention to kill, harm, rape, prostitute, or extort a victim to avoid punishment if he marries the victim with her guardian’s permission”.

In February various human rights groups called on the Kuwaiti government to repeal Article 182 “but the authorities have not taken any action yet”, Kuwaiti artist Amira Behbehani tells MEE. Behbehani is one the representatives of Abolish 153 group that fights for women’s empowerment in Kuwait and heads the group campaigning to repeal Article 182.

In the video, dozens of marriage certificates are suspended from the ceiling, appearing as though floating. Al-Hemd recreated templates of certificates and filled each blank part with words such as rapist, rape victim’s abductor, abductee and so on.

Another of his provocative works forms part of his 2016 installation, Indulgences: Reborn (2016). It examines the complex relationship between terrorist organisations and the often young uneducated youth that are recruited.

3. Zahra Al-Mahdi

Drawings of dissected human or animal organs exposed in glass cases are what 30-year-old visual artist, writer and filmmaker Zahra al-Mahdi is best known for. Since she was a child, Al-Mahdi, also known by her nickname "Zouz the Bird", was passionate about science, dissecting insects and animals, and drawing.

Her multimedia collages using crosshatched ink sketches digitally layered over photographs or videos are what also gained her notoriety and a huge following on social media.

In 2016 she also published her debut graphic novel We, The Borrowed, that examines how difficulties in communicating can physically impact our bodies. The book, available in English and Arabic, was born from her frustration with all things related to bureaucracy and “processes that are supposed to make life easier, but end up creating more complex difficulties”.

Al-Mahdi says that ironically, studying subjects other than art at university helped her become a better artist: “I wanted initially to go to art school, but I thought I had more job opportunities if I went into English Literature. What's funny is that I ended up studying so much philosophy and so much history that it helped me with the type of work that I do more than art school could have... it has immensely given me depth and content and critical thinking.”

Consequently Al-Mahdi doesn't consider herself an artist, rather “a thinker”. Her work aims to raise questions and provoke reactions.

“I think of my style as something that is extremely silly. But there are a lot of people that think my art is scary because it leans towards the macabre. Anatomy can really tick people off… A lot of people think that there might be something wrong with me. Well, I think that the best way to talk about an issue that's difficult to talk about, is to joke about it.”

A satirical analysis of Kuwaiti society and identity is at the centre of her mockumentary series on YouTube titled Bird Watch (2017). Each episode, made of animated sketches on live action, has a topic with a critical message behind it. In the first episode "Middle", birds observe the way Kuwaitis live in a consumerist society and “with a mentality of owning things that aren't rightfully theirs”.

In the video it’s not only birds who observe Kuwaitis while they go about their life, but also migrant labourers, working primarily in the construction and domestic sectors. In the video the workers are defined as “creatures that know us [Kuwaitis] better than we know ourselves… Creatures that surround us every day. Maybe we don't see them, but we depend on their existence every day”.

4. Amani al-Thuwaini

Born in the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, half-Ukrainian, half-Kuwaiti multidisciplinary artist and designer Amani al-Thuwaini, 31, began drawing as a child, influenced by Soviet cartoons, matryoshkas (Russian dolls), and fairytales.

Her eclectic and bold mixed media work addresses consumerism, the way people relate to luxury, and how they can lose their individuality by investing in material objects. With a high level of purchasing power in a small population, GCC countries are an attractive market for luxury brands.

“Shopping is part of the region’s culture and it has always been part of Kuwait’s identity, even though the definition of what is luxurious changed throughout time with changes in trade and market trends.”

Featured in solo and group exhibitions in Kuwait, London and Italy, much of al-Thuwaini’s work is in largely wall-based sculptural forms. Modernism, fetishism, gender and power manifest in hybrid objects.

They also focus on wedding and dowry traditions and how they evolved in Kuwait. Recently she even launched her own business Dazzalab, which offers creative options for dowries.

Her 2017 wall installation Elibelinde – named after the Turkish word for “hands on hips”, symbolising fertility and motherhood, combines cultural symbols of marriage through different periods of history. The geometrical figure has a buqsha on her head - a bundle of fabrics considered to be one of the earliest forms of dowry in the Middle East and Islamic culture. It appears here in the form of a pumpkin carriage as a reference to the Cinderella fairytale.

The ritual of presenting the dowry to the bride is explored in the wall installation Dazza, (2016), the name derived from the Arabic verb to send. A centuries-old tradition in Kuwait, the dowry has been modernised from a bundle of fabric to include international designer goods among the gifts.

On the wall installation, sadu weaving (embroidery in geometrical shapes traditionally hand-woven by Bedouins) flanks a central leather section resembling an oversized Chanel bag. The iconic French brand logo is replaced by the Arabic word Dazza in gold colour Plexiglass.

“The goal behind the work is to open our eyes to our day to day rituals and traditions which are taken for granted and questioning how those change with our constantly changing world”, al-Thuwaini says.

5. Anas Alomaim

Through abstract notions and symbolism, most of Anas Alomaim's mixed media work tackles concepts related to diversity and alternative points of views. “There are topics that cannot be expressed openly. Not to say that there isn’t a potential to talk about sensitive topics in Kuwait, it is a matter of how to convey the message.

"That is why I resort to abstract and symbolism so it could be understood without losing its meaning. It’s all about layered meanings,” Alomaim says.

The 38-year-old artist, architect and professor of architecture at Kuwait University, has taken part in several solo and group exhibitions in the US, Dubai and Kuwait. He is also a renowned jewellery designer - his ethically sourced and made label Oumaem was announced in March 2020 as one of the finalists of the second edition of Fashion Trust Arabia.

“Each individual has his own perspective on things. If we allow our vision to look at things differently, from different angles and give the way to our minds to explore the various aspects of a matter, we can overcome issues such as inequality and the rejection of the ‘other’, locally and globally,” Alomaim says.

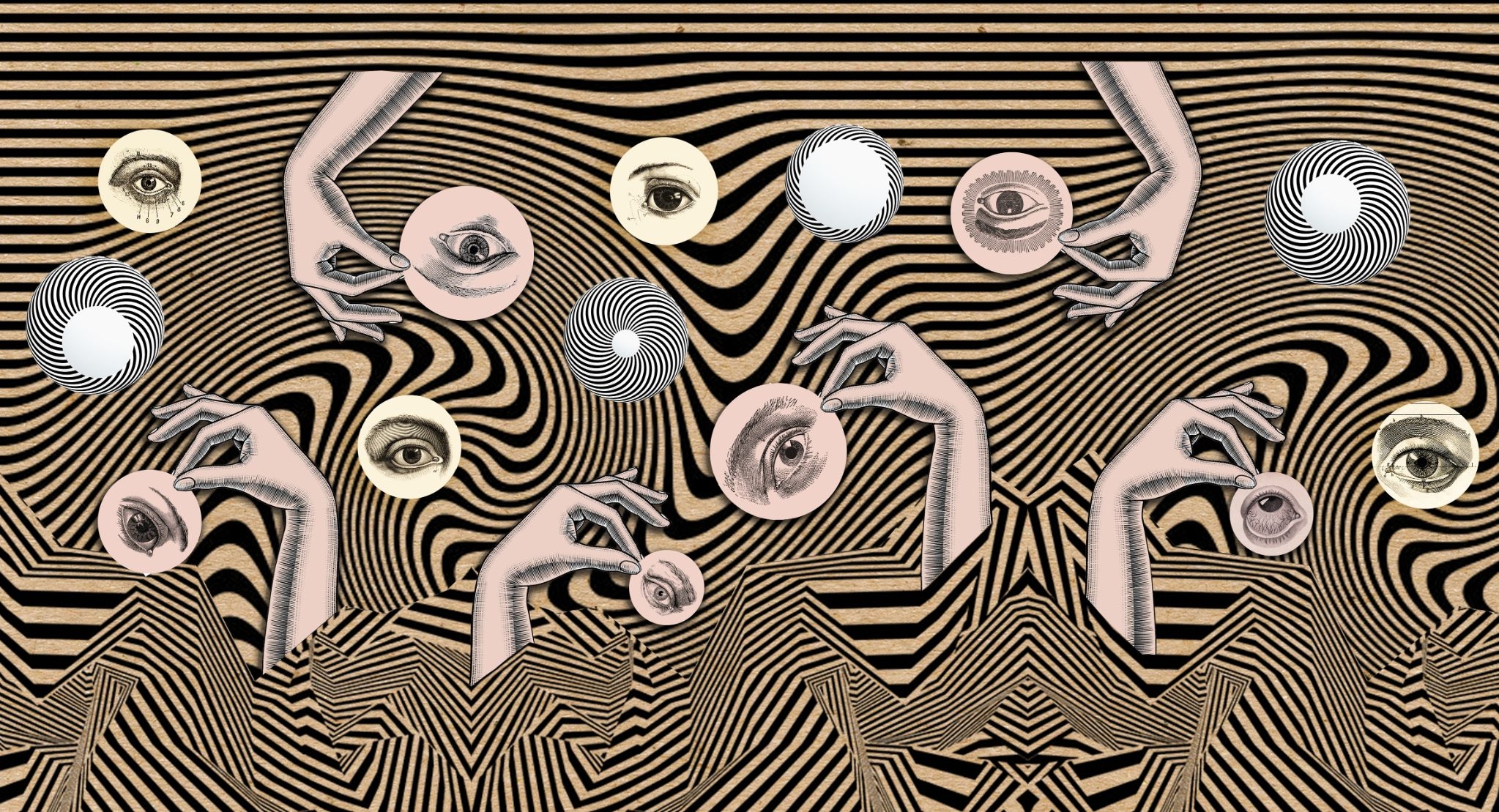

One of his more recent pieces, Mis-, which was shown at Kuwaiti gallery The Hub in 2019 at an exhibition named Filtered, is a collage that expresses the illusion of reality where the “truth is always filtered”, causing possible miscommunications and misinterpretations. Against a psychedelic background, different cut-outs of eyes are held up by hands suggesting control over one’s understanding of truth.

“It is important for me to create objects that are unique but also appealing to a wider range of the public. The most important thing for any artwork is to look interesting and to hold a concept that serves a bigger purpose.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.