'Armageddon': When coronavirus struck a Tehran hospital

It was like scenes from an Armageddon-like movie made in Hollywood instead of a real-world Tehran hospital, Hesam Khezri said, describing the state of Masih Daneshvari during the first days of the coronavirus outbreak in Iran.

“Looking down from the rooftop of the hospital…you could see dozens of ambulances rushing with their sirens blaring. People in sanitary clothes were going hurriedly from side to side transferring patients on stretchers,” Khezri told Middle East Eye.

Khezri is a doctor’s assistant working in the hospital's surgery department but was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) as the demand for more personnel to deal with the crisis grew.

He was diagnosed with Covid-19 on 1 April.

“Suddenly, we were spearheading the fight against Corona,” Khezri said of Masih Daneshvari, a big hospital built in a mountainous area north of the capital.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

'Within 24 hours, between 650 and 700 people were taken to our hospital'

- Hesam Khezri, doctor's assistant

“We were all taken by surprise. By no means, could the hospital staff have predicted that within 48 hours more than 20 different wards, including three for emergencies, would be filled with patients suspected of having coronavirus,” Khezri said.

The Iranian health ministry publicly announced the first two cases of Covid-19 in the country on 19 February.

A few days later, Iran became one of the global epicentres of the virus. At the time of publishing this article, there are more than 76,000 confirmed cases and more than 5,000 deaths in Iran.

Since the onset of the outbreak, Masih Daneshvari quickly became the primary destination for infected patients, with Iranian health officials also sending suspected cases there.

Khezri said the situation was made complicated by the state of panic felt by the hospital staff who had little experience in dealing with a new virus that is yet to have a cure.

“Within 24 hours, between 650 and 700 people were taken to our hospital, a trend that gained serious momentum over the next few days”, he added.

The rapid increase in the number of cases and the death toll saw other hospitals and medical centres in Tehran join the efforts to contain the spread of the virus.

Iranian Health Minister Saeed Nemaki recently said that despite the state of the first days of the outbreak, Iranian medical staff are already much more experienced now than they were at the outset.

The first wave of infections had caused fear and pushed people, either suffering from coronavirus symptoms or wishing to be tested, to rush to the hospital.

“A large number of people could have contracted the virus in the hospital during the early days,” Khezri said.

But, he added, the situation eventually improved at Masihi Daneshvari with fewer people seeking hospital treatment and medical staff having gained some experience in how to manage the inflow of patients.

Today, people presenting with acute difficulty in breathing and dry coughs are sent to the relevant departments for blood tests and CT scans for their lungs.

Meanwhile, patients with no pulmonary problem are sent into quarantine either at home or in an isolated ward in the hospital.

The frontline

“I will never in my life forget these days I am going through. [We see] patients who are in good condition in the morning but then show severe symptoms at night and die before the next morning,” Fatemeh, a nurse in Masih Daneshvari, said using only her first name.

Fatemeh said fear was prevalent at the beginning of the crisis, especially when some of the staff contracted the virus themselves.

“But now, as the cases increase, what matters most to us is saving people’s lives.”

In Iran, as is the case in many countries, there was a shortage of medical staff on the frontline of the outbreak.

Nurses and doctors have had to spend numerous long days and nights at the hospital, with many retired doctors and nurses returning to assist the exhausted personnel.

Being most at risk for exposure, health professionals are being applauded all around the world for their relentless efforts and dedication in battling the virus.

According to Iran’s health ministry, 43 medical workers including doctors have died so far after contracting the disease.

Fatemeh said Masih Daneshvari Hospital has suffered from a severe shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) – such as face masks, gloves, and sanitary clothing - at the start of the outbreak, and although the problem is being gradually solved, the damage was already done.

“We received a big shock at first,” she said.

“The huge number of cases and our poor experience in dealing with the disease has led us to witness some of our colleagues getting infected and has increased our anxiety in dealing with coronavirus patients.”

Medical staff either work 19-hour shifts and are off for 48 hours afterwards or works 7am-2pm shifts every day.

A few days after the outbreak, some retired physicians and nurses voluntarily joined the staff, reducing the initial pressure.

Dealing with grief

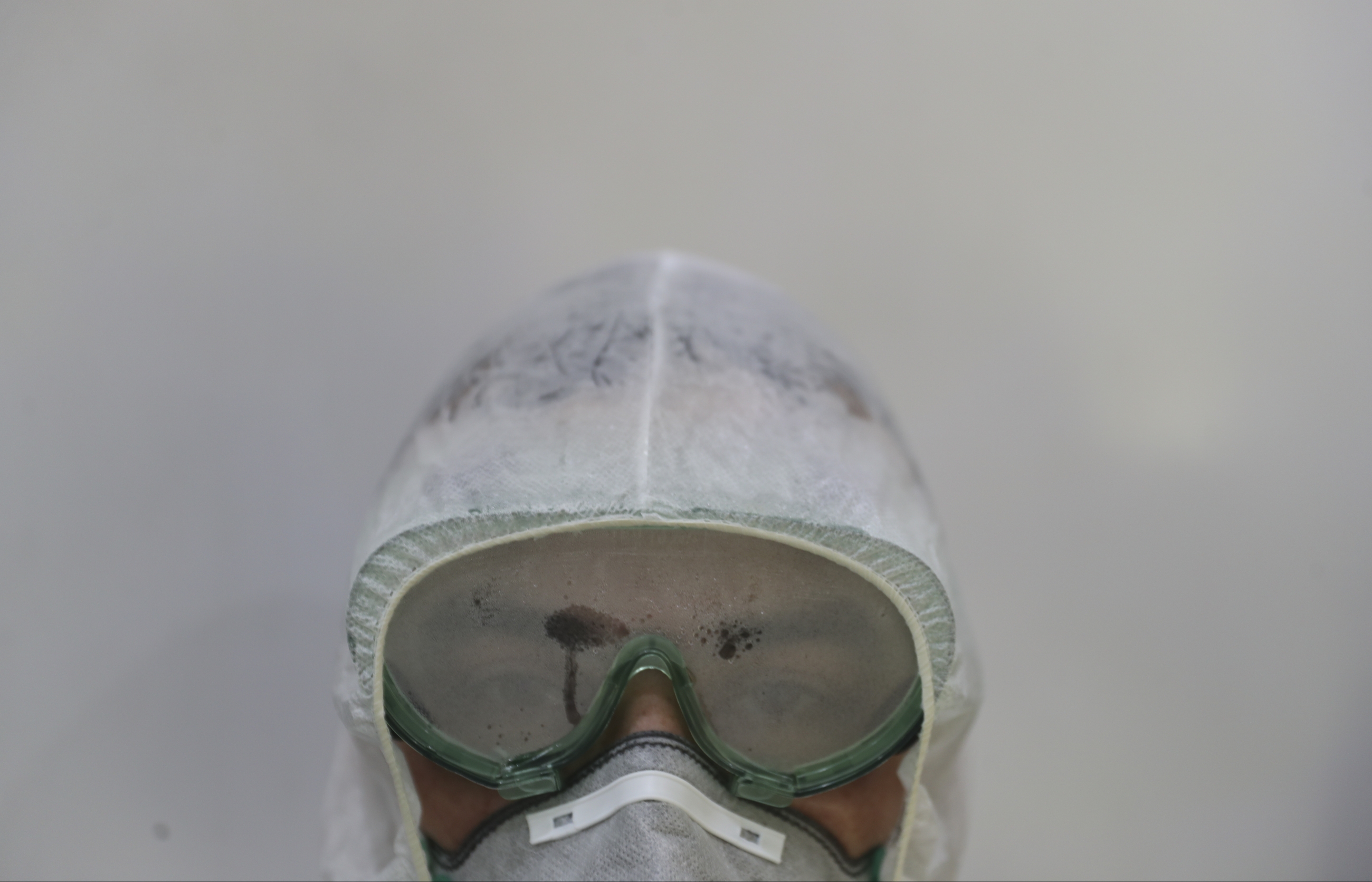

Hospital staff sometimes have to wear PPE for 19 hours at a time, which Fatemeh says can feel like a nightmare, but this is not their only problem.

“We work for many hours and days and have to isolate ourselves because of our exposure to the virus. Many of us have not seen our families for fear of transmitting the virus to them,” she said.

Many of the medical workers were not able to spend the eve of the Iranian new year, Nowruz, with their families because they had to stay at the hospital.

“Seeing the death of patients has caused us a lot of grief and sorrow. We have to sometimes sing together and play instruments to get over the sad situation,” Fatemeh said, praying that the crisis will be over soon.

Besides the medical staff, many other workers are part of the tragic scenes, including the personnel in charge of carrying the corpses to the morgue, those in charge of maintaining the quarantined areas of the hospital, and the catering staff taking care of the patients’ meals.

They too have to wear PPE as they carry out physically demanding tasks while also being exposed to Covid-19 patients.

In the coronavirus unit at Masih Daneshvari, a member of the cleaning crew has taken the initiative, in addition to his daily duties, to talk to patients, to listen and entertain them, and to improve the morale of his colleagues.

US sanctions

The coronavirus crisis in Iran has been compounded by the harsh sanctions imposed by the United States, which has essentially cut Iran off from the international banking system.

While Washington has repeatedly insisted that medicines and humanitarian goods are excluded from the sanctions, restrictions on trade have made many international banks and companies reluctant to do business with Iran.

Iranian officials have rejected recent US claims that Tehran can still import medicine and food, saying that no company is willing to sell medicine to Iran out of fear of punitive measures by Washington.

Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif has warned of a humanitarian catastrophe if the sanctions against Iran remain in place.

A large number of civil and humanitarian groups across the world, as well as officials and even some US congressmen, have also called for the temporary lifting of sanctions on Iran during its battle against coronavirus.

One doctor at Masih Daneshvari said there is, in fact, no shortage of medical equipment at the hospital, with enough ventilators and beds in the intensive care unit.

But, the problem, he said, is the shortage of medicine caused by the sanctions.

“A pack of Tamiflu [an antiviral medication] is sold at over $100 on the black market in Iran. Had it not been for the sanctions, this medicine would cost less than $5,” the doctor told Middle East Eye on condition of anonymity.

“Another anti-coronavirus drug, Actemra [tocilizumab] is now traded at $3,000 on Iran’s unofficial market, while the same medicine would not be worth more than $100 had the situation been normal. That is the case with other imported medicines.”

Masih Daneshvari Hospital is a specialised centre for lung diseases and one of the best medical establishments in the Middle East. It is also presided over by prominent Iranian politician Ali Akbar Velayati.

Warnings

But the case is different for other hospitals in Iran.

According to various reports, many hospitals in the country lack appropriate medical equipment.

Other reports say that medical staff in many hospitals, particularly in small towns, face shortages of basic necessities such as face masks, sanitary clothes and goggles.

The overall situation of the coronavirus outbreak in Iran is improving according to the president and some health officials, although the daily number of reported cases in the country has not yet dropped.

Nevertheless, the number of suspected cases or infected people admitted to Masih Daneshvari Hospital has significantly decreased compared to the early days of the outbreak.

According to the doctor who wished to remain unnamed, the number of cases has dropped from 600-700 per day to 150.

He believes that Iran has already reached the peak of the disease and it will be on a downward trend.

The doctor cautioned, however, that if social distancing measures and restrictions on people’s activities are rolled back too soon, the country will suffer a more severe outbreak and a second peak.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.