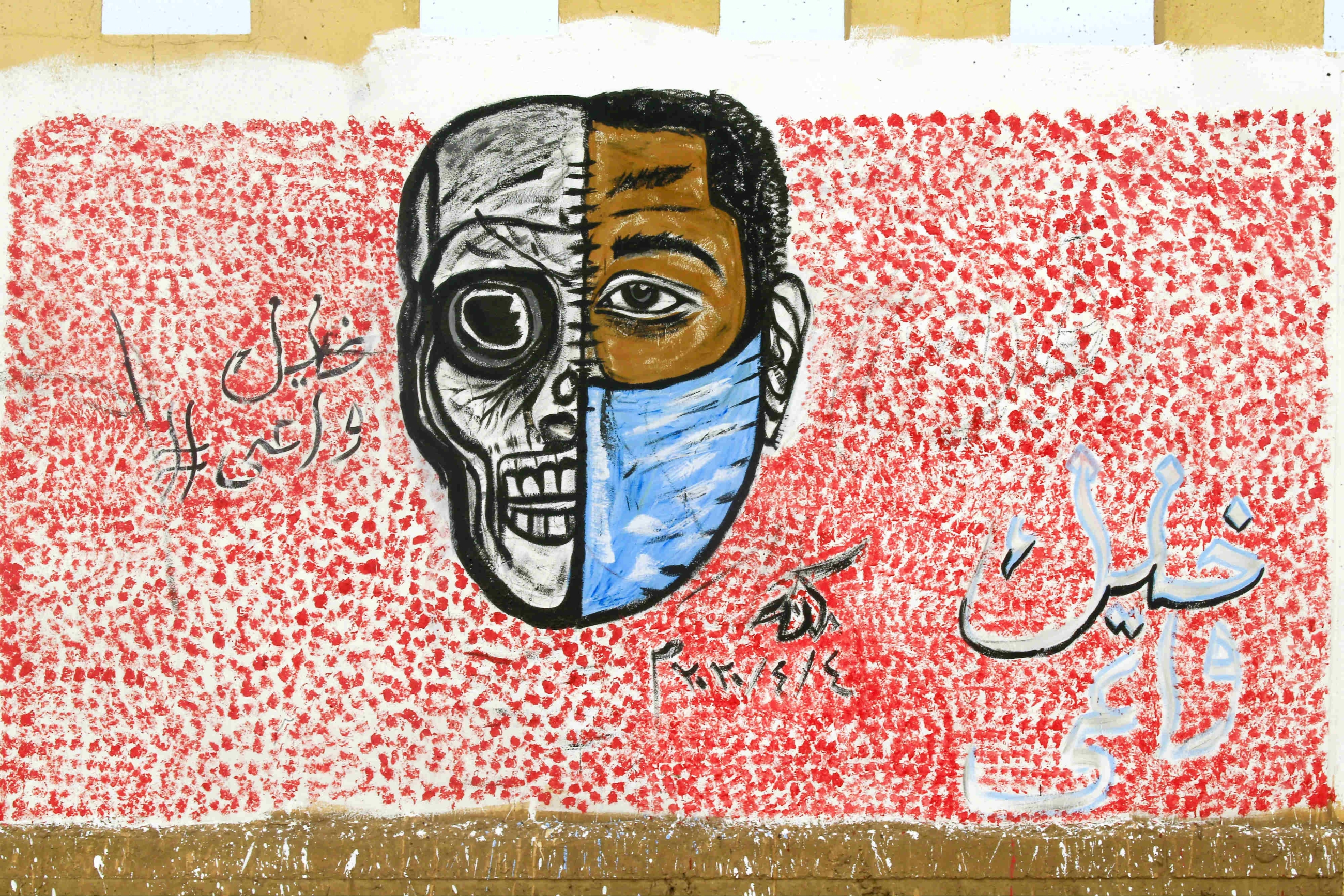

Coronavirus: Is Sudan's health system in danger of collapse?

Despite Sudan still having a comparatively low number of confirmed cases of coronavirus, a sudden jump in cases since the beginning of May has raised serious questions about Sudan's ability to handle the situation, given its fragile health system.

In a speech last week, Minister of Health Akram Ali Altoum warned that Sudan had entered a “dangerous stage” amid a severe shortage of medical staff, medicines and protective clothing, among other items needed to combat the virus.

The numbers of confirmed cases of Covid-19, which first appeared in Sudan on 12 March, has suddenly increased in the past few days, reaching 778, including 45 deaths, as of Wednesday.

Moreover, the figures indicate a high rate of mortality as well as a low rate of recovery.

Medical sources further disclosed that hospitals have witnessed a sharp increase in cases among medical staff, making hospitals themselves another focal point of the pandemic.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Adding to the bleak picture, disaster management and public health experts say the measures taken so far - including the full lockdown of the country and especially Khartoum, which had become the focal point of the pandemic - will have a profound negative economic and social impact.

'They will simply die'

In his speech, Altoum spelt out the lack of resources in the health system and warned that the country will run out of most medicines within two weeks.

Addressing the nation, he said: "Unless people commit to social distancing and the other preventive measures, they will simply die.

“We inherited a deteriorated health system from the old regime. We have no capacities like other countries which have also failed to confront the coronavirus.

"So we have no capacity more than giving you Panadol and other simple medicines. If you are not lucky enough to recover, you will die; so you have to commit to the preventive measures," he warned.

“Our stores and hospitals have run out of stock of some life-saving drugs and after two weeks we will run out of most of medicines, including infusion fluids... Our medical cadres are working without protective gear and other medical supplies. They are working in very tough circumstances, so there is a big risk to their lives,” he stressed.

The Ministry of Health of the transitional government - in place since August following the ousting of authoritarian leader Omar Bashir - has confirmed that the pandemic has reached 14 out of the 17 states outside of Khartoum, where the health system is even weaker than in the capital.

Bakri Bashir, a Sudanese public health expert, told Middle East Eye that the increasing numbers of cases proved how the public health and clinical structures in the country were too weak to handle the huge challenge of responding swiftly to the pandemic.

In light of the situation, the United Nations last week called countries around the world to help Sudan financially.

“In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, the government and people of Sudan could experience untold suffering unless donors act fast to shore up a country still in transition,” said Michelle Bachelet, the UN high commissioner for human rights.

Medical staff infected

A medical source told MEE that the rapid increase in the number of medical staff being infected by the coronavirus was a matter of concern for the Ministry of Health, with around 17 workers so far having tested positive.

The source, who asked for anonymity as he was not authorised to talk to the media, further disclosed that the medical director of the biggest isolation centre in the Gabra area of Khartoum had been infected with the virus.

He said that at least 13 health facilities have been closed just in Khartoum state as a result of the pressure from the pandemic, warning that the country's health system was on the edge of collapse if the international community did not quickly provide assistance.

“The rising numbers of infections among medical staff is worrying, and the lack of accurate information on official numbers has increased anxiety among health workers who have become largely demotivated,” said Bashir.

Government disputes

Africa as a whole has registered 42,769 coronavirus cases so far, with 1,759 deaths. Despite the rising number of casualties in Sudan, they are still lower than in other countries such as South Africa, Egypt, Algeria, Morocco and some West African countries.

However, Bakri Bashir, who is also a health advisor for an international medical humanitarian organisation, argues that the lack of faith in the country's health system was a worrying sign and the situation in the country should raise the alarm.

“We have seen signs of health system failure, with many hospitals stopping providing regular non-Covid-19 medical services, a lack of essential medications, the loss of a significant amount of staff due to infections, and high burnout among medical teams,” he said.

“The limited testing capacity and a highly centralised testing strategy don't allow us to know the full scope and the whereabouts of the outbreak in the community.”

Bashir hinted that disputes between components of the transitional government were also another obstacle to Sudan’s capacity to combat the coronavirus.

“The clear lack of coordination between the different government agencies and bodies has caused significant delays in enforcing any decisions,” he said.

Threat of instability

Alsadig Alzain, a Sudanese disaster management expert, told MEE that the economic and social impact of the pandemic on African countries, particularly Sudan, will be even bigger than the direct health impact of the virus.

Alzain, a professor of environmental science at Al-Ahliya University, warned that the long-lasting spread of the pandemic, coupled with the lockdown measures, would threaten the stability of the country, adding that “even if we control the disease, other challenges will appear immediately afterwards".

“We have to see this pandemic as an economic disaster, a security disaster and a humanitarian disaster - and they’re all interrelated," said Alzain.

"We need to anticipate the consequences after the disease has been contained, because our systems are already fragile and don't have the flexibility to absorb this economic deterioration, unlike rich countries .”

New economic model

Alzain added that African countries that are more economically fragile need to adopt a new economic model to mitigate the domestic and global economic effects on poorer people.

“There are many ideas here, such as distributing food or raw materials to the people, lifting or decreasing taxation, giving some services for free such as electricity or water, easing the interest on bank loans, or activating the availability of microfinance, that can mitigate the economic suffering and social impact of this disaster,” he said.

Bashir told MEE it was important to adapt World Health Organisation (WHO) measures to the circumstances of African countries, especially Sudan.

He said key measures to help control the coronavirus in Sudan were better coordination between different stakeholders, mass testing, and the separation of incident response centres from regular healthcare facilities.

“Regardless of how grim this picture is, I believe that with more coordination, the firm enforcement of public health interventions, mass community testing, and the building of basic decontamination sites - to accommodate and shield the health workforce from the virus and allow hospitals to continue operating - we might gradually be able to contain the disease,” he said.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.