Could Joe Biden really close Guantanamo Bay prison if elected president?

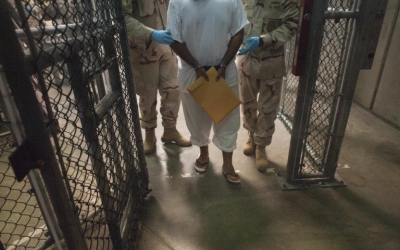

There are 40 men left at the Guantanamo Bay prison camp, and their lives may very well depend on who wins November's US presidential election.

In the case of a victory by President Donald Trump, the chances of a Gitmo closure are slim. Still, former vice-president Joe Biden has vowed to make good on past promises to shutter the infamous detention centre.

"[It] undermines American national security by fuelling terrorist recruitment and is at odds with our values as a country," Biden's campaign told the New York Times in late June.

'Civil liberties groups, human rights groups, detainees, lawyers and others don't want detainees to be brought into the United States for indefinite detention, because that's not closing Guantanamo. It's just changing the zip code'

- David Remes, Guantanamo Bay defence attorney

While closing Guantanamo Bay prison, located on a contested US military base in Cuba, was also one of president Barack Obama's campaign promises, political pushback at the time blocked the initiative.

David Remes, a human rights attorney who has represented numerous Guantanamo detainees over the years, told Middle East Eye that since those barriers remain in place, Biden's plan to close Guantanamo Bay would be an uphill battle.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

"Biden is going to face some of the same obstacles that Obama faced, namely the law that prevents detainees from being transferred to the United States," Remes said, referring to legislation enacted in 2009 that prohibits the use of funds to move Guantanamo detainees to the US for any purpose.

Remes said he would be "very surprised" if Congress lifted the ban unless both the House and the Senate were controlled by Democrats, and in the US it is rare for one party to control both the executive and legislative branches of government.

Still, experts have questioned whether the ban imposed by Congress is legal, since Article II of the Constitution gives the president exclusive authority to determine where military detainees are held, though challenging the ban would cost Biden a lot of political capital.

Biden said in December that he would need congressional approval to close the facility.

'We cannot trust the king'

Instead of working to get prisoners moved to the US, Remes said it was more likely Biden would revive the parole-like review board mandated by an executive order in 2011, which created a panel of representatives from six government agencies charged with reviewing the cases of prisoners that had not been charged.

The parole board, which requires a unanimous vote to trigger a release, only determines whether an inmate currently poses a risk to US security, and does not consider guilt or innocence.

Using the mechanism, the Obama administration was able to secure the transfers of 204 detainees out of Guantanamo.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a former Guantanamo detainee who was held there for more than a decade before being released by the parole board in 2016, told MEE that he welcomed Biden's plans to close the prison, saying he was "happy to hear" the presidential candidate had chosen to take a stand on the issue.

Slahi, who wrote a memoir detailing the torture he was subjected to during his confinement, warned that Guantanamo "belongs in a dictatorship, not in a democracy".

"The violence of the state must be kept in check by a functioning and independent justice system," Slahi said, pointing out that Gitmo's war court, detention centre and parole board were all presided over at least in part by US military or intelligence service representatives.

"History taught us that we cannot trust the king to call all the shots unchecked," he said.

While the board that released Slahi remains active, not a single prisoner has been approved for release since the Trump administration took office in 2017.

Ahmed Muhammed Haza al-Darbi, the only person to leave Guantanamo's detention centre during Trump's presidency, was cleared during the Obama administration and transferred to a prison in Saudi Arabia in 2018.

The Trump administration has blocked the other five inmates who were cleared for release before he took office, leaving them in detention limbo.

'Changing the zip code'

Of the other 35 people that remain in the prison camp, seven are being tried in Guantanamo's war court, two have been convicted (though only one has been sentenced), three have been recommended for trial, and 23 - deemed "forever prisoners" - are being held without charge or trial in indefinite detention.

"Civil liberties groups, human rights groups, detainees, lawyers and others don't want detainees to be brought into the United States for indefinite detention, because that's not closing Guantanamo. It's just changing the zip code," said Remes.

"Those detainees who are not charged with a crime should promptly be sent home," he continued.

Daphne Eviatar, director of Amnesty International USA's Security with Human Rights office, believes there has been enough of a shift in American politics for Biden to be able to follow through with a total closure of Guantanamo Bay's prison camp.

"I think that we're very likely to see some changes in Congress," said Eviatar, whose work as a human rights lawyer has focused on Gitmo detainees for more than a decade.

Over the years, she said, advocates have had time "to develop solutions for each of the 40 cases" remaining at the camp.

The vast majority of the prisoners at Guantanamo could be approved for transfers to their home countries, while those on trial at the military commissions' war court would hopefully be able to agree on plea deals and be transferred to US facilities to finish out whatever time they were sentenced to, she said.

Gitmo's war court: 'An abject failure'

The war court at Guantanamo has been a complicated, haphazard experiment led by the US military that has seen constant delays, and much of the law related to commissions remains unsettled and in dispute, among many other issues.

While all seven defendants currently on trial were arraigned between 2011 and 2014, not one of their cases has advanced beyond the pre-trial process.

Defence attorneys and prosecutors alike have quit mid-case over objections to the court's complicated legal system.

Much of what has stalled the pre-trials being held at Gitmo has involved the debate over what can be considered torture. Congress in 2009 passed legislation prohibiting the introduction of some evidence gathered through torture or "cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment".

During the pre-trial process, defence attorneys have argued that under that law the vast majority of evidence gathered in their clients' cases should be deemed inadmissible.

"Most of the stuff that happens [at the war court] is pretty much a charade," said Maha Hilal, whose doctorate in justice, law and society focused on Muslim rights amid the US "war on terror".

"The whole thing is so disturbing.

"Everyone knows it's torture, I'm sure even the people who are saying it wasn't torture know it's torture," Hilal said.

Remes agreed, calling the war court "completely dysfunctional".

Instead of going forward with the military commission trials, he said that Congress should lift the ban on transfers to the US and try those charged with crimes under the US Federal Court system.

"The Federal Court system is the right place to try them, not the military commissions, which are an abject failure," Remes said.

While deemed unlikely in the past, Remes said he thought there was room within the current political arena to do so, given some support from Congress.

"If Congress eliminates the ban on bringing them to the US, then conceivably they could be brought to the US for trial despite potential political issues," he said.

"Because you wouldn't necessarily be talking about keeping them here, or keeping them here indefinitely. You're talking about proceeding in a system that is known quantity, that is predictable and can certainly be more effective than the military commissions."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.