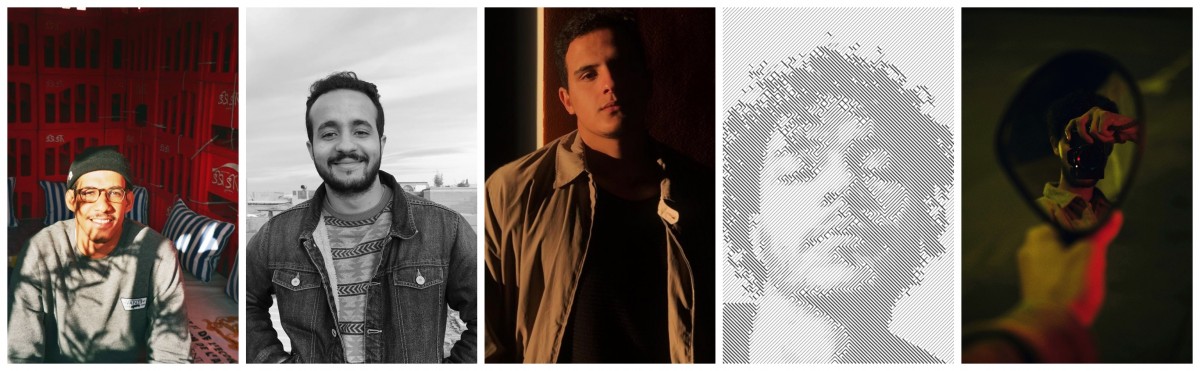

Meet the new vanguard of Moroccan photography

Breaking into an established art scene can be tough for young artists who have yet to make a name for themselves. This is why 14 emerging Moroccan photographers recently decided to form Noorseen, an art collective they hope will help them harness resources and share insights through the collaborative process.

An amalgamation of the word “noor”, which in Arabic means “light”, and “seen” from the English verb “to see”, their name fuses two cornerstones of photography.

Most importantly, it reflects their joint desire to offer a fresh vision from Morocco and to shine a light on its hidden talents.

“A lot of visible works of photographers on Morocco have similar tropes; the picturesque medina, the traditional costumes, the portrait of an elder,” says 22-year-old Noorseen member Mehdi Aït El Mallali.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

“We want to show the other side, which is an expression of the Moroccan youth. We show Morocco through our own eyes, as a member of this society.”

A collective momentum

Since they all hail from different regions in Morocco, some more peripheral than others, this need to belong to a buzzing artistic tribe is at the core of their initiative.

"We all met on Instagram. In Morocco, the community is small, and we were aware of each other,” says Aït El Mallali who lives in the town of El Hajeb, in the foothills of the Middle-Atlas. “We originally created an informal group sharing bits of information and tips, so the collective stemmed naturally from our relationships. The idea was already floating around when we decided to make it happen.”

"We had been interacting for a long time," says 23-year-old Marouane Beslem. "Then as the Covid-19 pandemic took hold of the country and the artists found themselves in lockdown, their first project was born - a photography-based creative exercise they dubbed the 'Photo Conversations'.

“We challenged each other to kick-start our collaboration,” Beslem says. “Before formally founding the collective we assigned ourselves the task of documenting our confinements at the height of the pandemic. So, every one of us produced a body of work around this theme."

For the assignment, they sorted themselves into random pairs, each tasked with reinterpreting any of their partner’s existing photographs through their own lens.

The correspondence could pick on anything from form to meaning, to create a stimulating visual discussion between the photographers, despite the artists’ individual isolation.

The completed series will soon be published side by side as diptychs on their new Instagram page, and they hope it will encourage others to experiment and share their own “photo conversations”.

The artists are quick to emphasise the collaborative nature of their group - their decision-making is democratic and uncompetitive. In fact, they’d all long been fans of each other’s work. “The photographers who are in the collective were already some of my favourites,” Hind Moumou, 25, says.

“I’ve been inspired by someone like @rwinalife [Ali El Madani, another Noorseen member] since my early days as a photographer. Jalal Bouhsain [@oddabe] is one of my favourite inspirations too,” Aït El Mallali adds.

But cohesion doesn’t equate to uniformity, and Noorseen is an opportunity for the artists to challenge their individual practice and learn from each others’ work. “We’ve also improved our skills by helping each other with editing and technicalities,” Beslem says.

The pieces they produce are eclectic. Not only do they all use different mediums, including film, digital, or smartphone cameras, but their visual language is also broad.

Raised in the city of Beni Mellal, in the Moroccan hinterland, Anass Ouaziz, 27, is fascinated by the beauty emerging from everyday life. His photographic compositions are minimalistic views of day-to-day encounters often underlined with ochre hues that reflect the palette of his hometown’s architecture.

“For me, photography is an observational practice where I find beauty in the mundane. I am interested in the in-between, in calm moments where seemingly nothing happens,” Ouaziz says.

Meanwhile, Aït El Mallali presents cinematic landscape photographs and portraits of the people of his town, Al Hajeb. His elegiac images of nature reflect the fertile agricultural region he grew up in.

Noorseen member Hind Moumou, a 25-year-old English teacher from Rabat, experiments with photos and short videos. Whether representational or more cryptic, there is a feeling of melancholy and solitude brooding in her images, not constricted to a specific style.

“What is my style as a photographer? I always ask myself this question. I don’t want to be limited to any style,” Moumou says.

“Having said this, I do get inspired by my dreams. They are very vivid and have always been a part of my inner life. When I am not planning for a photo, I mostly try to catch the feeling of a fleeting moment, and it becomes a visual diary where I can experience it again.”

Even when spontaneously documenting her immediate surroundings, her process is an intimate self-examination above all.

“I do believe that things that come up to you subconsciously are stronger, so I try to combine both levels,” Moumou adds.

For Ismail Zaidy, a 23-year-old accounting assistant from Marrakesh, the focus is his own nuclear family, which he photographs as a way to question close bonds and individuality in a typical Moroccan household.

Working with pastel colours, fabric textures and the golden light of his native region, the whimsical images of his siblings have earned nearly 50,000 followers on Instagram, and he is currently being mentored by renowned Moroccan photographer Hassan Hajjaj.

Making an impact

As well as using their cameras for introspection, these artists’ works delve also into their experience of Moroccan society.

Oujda-raised Marouane Beslem, in the north of Morocco, took a gap year after graduating in business management to explore his passion for photography. At the end of the year, he moved to Casablanca where he now documents life in his new city.

"I don't want to be trapped in a category," Beslem says. "I shoot my surroundings intuitively. I like it when a photo displays interesting contrasts of colours, lighting, composition, or messages. In my work, I prefer to disguise my views, but I also might shake up local prejudices.”

Like many members of the collective, Beslem is originally a street photographer. Through his brooding photos of Casablanca, he conveys the atmosphere of a neo-noir movie in which the characters are mainly young people. Some of his most compelling photographs feature intriguing juxtapositions.

One particular night shot shows a couple locked in a tender embrace to the backdrop of the Hassan II mosque, a landmark of the city. In another, female football fans feverishly show their support for their team at the stadium.

Currently, Beslem is researching his first documentary project that will address the collective memory and painful destinies shaped by the turmoil of decolonisation. “Oujda is near the Algerian border, so these issues are especially close to my heart," Beslem says.

"Being quarantined in my hometown made me rethink my photography and redirect it to a more conscious and purposeful angle. I want to make an impact on society.”

All of the artists have honed their craft independently, taking full advantage of whatever means were available to them at the time. They often developed their style with limited technical knowledge and means.

Zaïdy shot his popular photos on his Samsung Galaxy mobile phone from the rooftop of his family home. As a self-taught photographer, he was drawn to the simplicity of this medium, and while he now owns a regular camera, his phone camera is still his preferred companion.

As for Fatimazohra Serri, she had to defy the constraints of her conservative milieu. The 25-year-old accountant from Nador, in the northeastern Rif region, had to hide her work from her male relatives at first, worried that they wouldn’t approve of her creative work, which is mostly composed of stylised self-portraits.

One of only two female members of Noorseen, Serri’s striking compositions, full of symbolism, are an intimate exploration of womanhood.

Serri addresses the ambiguities faced by women navigating a patriarchal yet contemporary society in a fresh, visual manner, presenting traditional scenes, items, and costumes with a witty irreverence.

Her photographs have both a purely aesthetic appeal, while still being combative. And she does not shy away from questioning universal taboos, as seen in her bold take on the shame associated with menstruation.

“My style is conceptual and I stand from a woman’s point of view. I engage in subjects that are close to me, extracting them from my social environment,” Serri says. “I focus my projects on the issues that women are facing, specifically in the conservative society to which I belong.”

She is arguably one of the most powerful voices of her generation and, it seems, one of the few female ones since women photographers remain relatively under-represented in the country.

“Even if photography is a big part of their lives on social media, they are often in front of the camera and not behind it,” Moumou says. “This remains an individual choice, but we do want to encourage women to take that leap if photography sparks their interest.”

Breaking in

Just as rising to prominence on Instagram meant relatively unknown artists could get their voices heard within Morocco, it also meant they could bypass traditional art outlets and appeal to new audiences from the region and beyond.

And the next step? Professional recognition. "We need to be visible and showcase Moroccan talent,” Aït El Mallali says.

“Throughout national and international exhibitions or festivals, the same few names represent Moroccan contemporary photography. Why can't we? Young photographers could take over, and we want to amplify our voice."

While some of them have experienced their first institutional recognition, exhibiting at the inaugural event of the new National Photography Museum in Rabat this January, most have yet to see their visions exhibited in print.

"Specifically in Morocco, there is a sort of monopoly on the few exhibition spaces available,” Aït El Mallali explains.

“The gallerists often work based on personal acquaintances. They don't go out of their way to show emerging talents. Often, people get international recognition before gaining the attention of the local art world."

French photographer Daniel Aron, founder of Tangier’s Foundation for Moroccan photography, also says there is a lack of opportunities despite the vitality of the local scene.

At the 2019 inaugural exhibition of his foundation, he announced to local press that his project was born from a lack of any private foundations dedicated to the promotion of contemporary Moroccan photography.

“We want to help give momentum to young Moroccan photographers,” Aron said, “and will also encourage Moroccan collectors to take an interest in this art that they often disregard.”

Morocco-based Marie Moignard, a specialist in Moroccan photography, art critic, and curator agrees. “The local scene is currently bursting with energy.”

Referencing Koz, another collective of Moroccan visual artists that emerged during the pandemic, Moignard says it’s natural for these creative forces to find ways to break their isolation and support each other, since the local ecosystem is not yet structured for them.

“I am very glad for these initiatives. Unfortunately, despite the variety of talents, a lack of professionalism and self-assurance are often preventing a lot of young artists from appearing in the institutional circuit. Forming a collective entity could help them to better navigate this move from Instagram to the traditional art world.

“Most importantly, public and commercial institutions must fully support this movement. They should engage with young talents and accompany them in their learning curve. They should also be more willing to take risks because photography is not always popular with Moroccan art collectors who are sceptical of its reproducibility,” she says.

While the Noorseen artists have found each other and a route to success via Instagram, they are aware of the platform’s limitations: “Instagram trivialised photography,” Beslem says.

“It became a consumable product. Yes, it is a powerful tool. But when people judge a photograph based on likes, they end up reproducing popular gimmicks. This kind of conformism levels down the local scene. We want to stand out from it.”

Right now, their priority is to become financially independent so that they can take on more demanding projects. "We want to publish a fanzine presenting our works. We’re thinking of practical ways of supporting our ambitions," says Aït El Mallali.

"Creative independence is crucial,” Moumou adds. “We want to have full creative control and protection over what we create."

And this independence is instrumental to Noorseen’s project, as it aims to disrupt the mainstream representations of Morocco.

By taking control of the narrative, Noorseen is breaking away from stereotypical depictions of Morocco that draw on a folkloric vision recreating a tourist’s fantasy.

“We take Iran as an example, a country that is riddled with stereotypes,” Moumou says. “But when you look at the works of young Iranian photographers, you discover how multifaceted and rich contemporary Iran really is, and you see unexpected images that only young Iranians could produce.

“It seems like we’re always represented by others. We will be representing ourselves, as a native voice, as well as showcasing different styles. The picture must not be identified by the geographic origin first. We want to stand by ourselves and our visual storytelling.”

Noorseen's work is available on Instagram

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.