How China could shape Iran's economic future

Iran’s Islamic Revolution embraced a novel vision based on an idealistic economic model, which eschewed any preconceived capitalist or socialist blueprint in an attempt to establish a utopia transcending the global alliances and alignments of the Cold War era.

Forty years on, the Iranian rial has depreciated more than 3,400 times against the US dollar, and according to Iran’s central bank, there has been capital flight of some $100bn to countries such as Turkey in the past decade.

A fear of western penetration directs Iran's politics, which complement its economic model of self-sufficiency

After the the Iran-Iraq war, Tehran’s bid to tap into western capital markets without political reforms led to the creation of a peculiar form of a crony capitalism, running alongside the state-run economy.

Iran’s refusal to adopt internationally recognised protocols in the process of privatisation, and the absence of the prerequisites and structures required to transition to a market economy, led to unregulated and unscrupulous privatisation moves, which resulted in bankrupt industries and a failing economy.

As we see today, the trials of public and private figures for corruption and siphoning off billions of dollars is the natural product of Iran’s failed attempt at indigenous capitalism.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Reaching out to capital markets opens Iran up to the western - and specifically Anglo-American - hegemony of financial, legal and regulatory frameworks. This cuts across the ideological grain of the revolution, premised on a discourse embracing a struggle to challenge these hegemonies politically, economically or militarily.

Meanwhile, a fear of western penetration directs Iran’s politics, which complement its economic model of self-sufficiency. This has translated into a national effort to reinvent the wheel in both theory and practice.

With the rise of new strong economies within the globalised marketplace, international norms and standards are not dictated by the West anymore, but rather collectively. Other players such as India, Japan and China have the same, if not bolder, input as compared with the US, France or Britain in formulating and refining the rules and structures.

Foreign interference

Iran’s historical fear of foreign interference, reinforced by its isolation since the revolution, has paralysed Tehran in the face of western influence. A lack of soft power and active diplomacy has left the country to either retreat further into isolation, or to project itself through military force and confrontation.

Iran continues to view frameworks such as the intergovernmental Financial Action Task Force as tools to infiltrate its financial structures, with the malign intention of engineering political change. This world view stopped Iran from reaping any financial benefits from the 2015 nuclear deal.

Tehran believed that the nuclear deal would generate a steady flow of European investment into the country, while it scored low on areas such as ease of business or transparency, which in turn hampered any meaningful European interest.

Rather than addressing shortcomings at home and lobbying businesses in the West, Iranian diplomats pressured Britain, France and Germany to encourage their businesses to engage with Iran.

Tehran also miscalculated the strong ties of European businesses with the US. According to the Financial Times, JP Morgan’s $380bn market capitalisation exceeds that of the top five European banks combined - a clear indication of natural European interests, and of why former British Prime Minister David Cameron’s plea to Barclays to work with Iran was refused.

Beyond the revolution

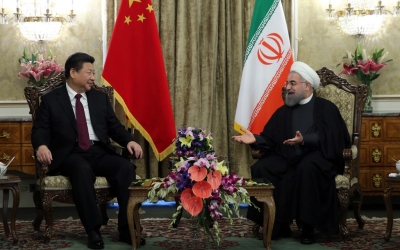

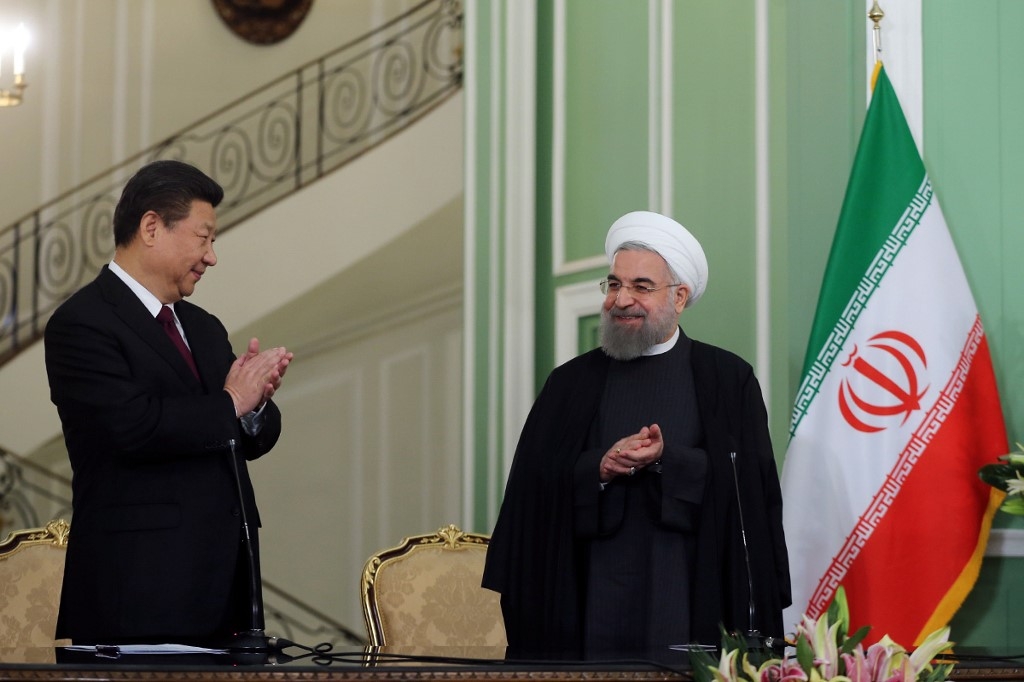

Today, Iran is preparing for a 25-year strategic accord with China under its “look East” strategy, while renewing an older pact with Russia. With Tehran’s resistance to “submitting” to what it perceives as the “western sphere”, and specifically US demands, the only way out of its dire economic and political impasse is to go to bed with China.

If and when this accord, the extent of which is unknown, is finalised, it will represent the most significant departure of Iran from its revolutionary principle of self-reliance. Supporters have scrambled to portray the deal as an anti-American exercise in line with Iran’s strategy to frustrate US dominance. They have gone so far as to cite the Quran in justifying their alliance with the communist state.

This change of heart after four decades of suffering economically should be applauded as a step towards the globalised economy, as well as an acknowledgment of the need for alliances with mightier players on the international scene. Iran can no longer assert that it can progress and prosper by cutting itself off from international markets, or that it can confront political threats without aligning with superpowers.

It will now lose the moral high ground vis-a-vis regional countries branded by Iran as client states of the West for the same type of strategic partnerships.

Iran has a lot of catching up to do while looking across the shores of the Gulf, pondering with envy why it waited so long to join a powerful partner and end its economic misfortunes and political fears. This Iranian epiphany is in itself a cause for celebration.

The second important byproduct of the accord is that Iran is finally signalling to the world that it believes, as a middle power, that it cannot retain an independent, non-aligned position in a highly volatile international scene. Iran tried and failed to achieve a rapprochement with the West; the East is where it can look to secure its economic and political stability.

But the timing of Iran’s eastward shift may steer it into a calamitous storm if the West continues ramping up pressure on China and Russia. Iran does not have much to lose, so it could become an even bolder nuisance in the wider Sino-Russian game plan against the West.

Transcending ideology

While Iran deserves credit for having taken a strong step towards the West through the nuclear deal, US President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the deal reinforced Tehran’s suspicious view of the West, fully tipping it towards Russia and China.

Despite the initial uproar against the China accord from a rather pro-western elite and population, a consensus seems to be emerging in Tehran, politically as well as within a frustrated private sector, that it is time to go East.

On a positive note, one may be surprised to see China finally getting Iran across the line, showing it the marvels of capitalism, free markets and globalism. Beijing can teach Tehran how to transcend ideology, transform a famine-hit nation and create a prosperous middle class by adopting the tenets of a free-market economy.

China may have unintentionally turned into the agent of the West, spreading its message from the East.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.