Beirut, broken and bruised: How photographers capture the trauma of their shattered city

The massive explosion that devastated Beirut's port on 4 August 2020 shocked everyone. Arriving at the scene with the first responders were the photojournalists, later joined by other photographers, drawn to the unprecedented scale of the devastation and its wealth of stories.

"We never saw an explosion destroy so much of the city in seconds," said Marwan Tahtah, 39, who shoots for Getty, AFP and Lebanon's Al-Akhbar newspaper. "Until now, every day I dream about that noise, those people … that sound."

Though he'd sped towards the blast site on 4 August, Tahtah said he struggled to take a photo.

"It took me ten minutes to focus - 'Be calm, Marwan. Concentrate' - and another 10 or 15 minutes to shoot a photo." He paused. "After that, it took maybe two days to stop thinking about it."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Too many stories

Tahtah's been shooting daily since the blast.

"There are a lot of stories happening at once. A fireman's funeral," he nodded to a church service on a nearby television screen. "There's the port story. There's aid arriving at the airport. There's a demonstration. There are volunteers helping clear peoples' homes.

"Until now I'm trying to take photos of the entire city, all the stories … [But] we can't take a photo of the entire city."

'It was important for the country, and for me. At the end of the day I'm Lebanese'

- Marwan Tahtah, photojournalist

In two decades working as a professional photographer in Beirut, Tahtah has shot his share of explosions and street protests - all dwarfed in the past 11 months, during which Tahtah's recorded the most euphoric and anguished moments of his career.

Since 17 October 2019, Lebanon has known the exhilaration of a trans-sectarian campaign of civil disobedience and popular demonstrations demanding root and branch political reform - "al-thawra" in local nomenclature.

In counterpoint, the country has been haemorrhaging from economic crisis, financial collapse and political paralysis.

"I remember the street, the fires, the people," he said of 17 October. "This was the first time all the people went to the street together. It was important for the country, and for me. At the end of the day I'm Lebanese."

One of Tahtah's celebrated photos of that 17 October demo centres on a young man - naked from the waist up, a scarf covering his face, mobile phone held aloft - silhouetted by the barricade blazing behind him.

Reflecting back upon that exultant evening is a picture Tahtah took a few days after the blast. It is just after dusk in the devastated port-side neighbourhood of Mar Mikhail; all is still and pitch-black. A pair of approaching headlights silhouette two human forms while, partially bathed in the green flood lamps of rescue teams, the crumpled ruin of the port's grain silo rises in the distance.

Documenting trauma

"The work I do is extremely draining," Dalia Khamissy sighs, against the persistent buzz of cicadas. "I listen a lot. I absorb people's problems all the time."

Khamissy, 47, was also shaken by what she found in the aftermath of the blast, not least because it echoed her previous work.

She may be best known for her civil war series The Missing of Lebanon, on which she's been working since 2010. She'd had no desire to shoot anything connected to Lebanon's civil war, she said, but the tragedy of 17,000 people forcibly disappeared during that conflict forced her hand.

A portrait series, The Missing of Lebanon captures women bereft of family members.

One shows Imm Aziz sitting on a daybed, leaning on her cane. On the wall behind her are arrayed portraits of her four missing boys, with sets of musbaha (prayer beads) hung between each frame. Unlike many of Khamissy's other subjects, Imm Aziz doesn't stare into the lens but gazes off-frame.

Khamissy admits her work shooting the destruction in the wake of the port blast feels like an extension of The Missing.

While the photos she's shot since the blast don't recreate the formal features of the series, her method of documentation is the same insofar as her framing of each portrait is conditioned by interviews with her subjects.

In both cases, she also feels her subjects are the victims of the systemic neglect of the political class installed by the civil war.

While interviewing members of the civil defence unit which lost nine firefighters and a paramedic in the port blast, Khamissy recalls a conversation with a random passer-by.

"The guy says, 'Listen, I paid my bill to Lebanon'.

"I said, what do you mean?

"He says, 'I have three brothers who are missing … kidnapped during the civil war.' When they found the remains of one of the firefighters, he went over to the dead man's father and said, 'Listen, at least you have closure. I still don't have closure from the civil war.'

"It's history repeating itself," Khamissy says.

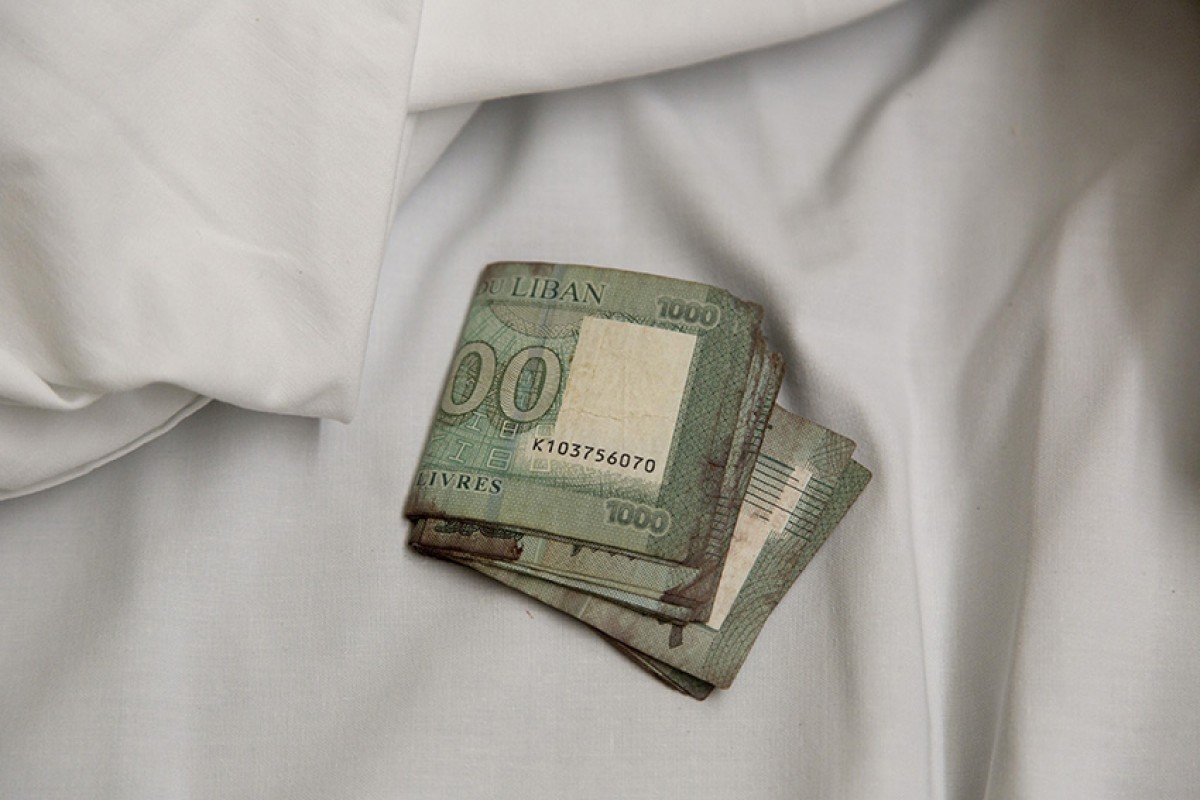

Rather than sharing a photo relating to the grieving families of the firefighters, Khamissy produces a photo centring on a blood-smeared wad of L£1000 notes - L£18,000 (about US$2.25) in all.

The money had been in the pocket of Georges, a 79-year-old taxi driver who was badly injured in the explosion. His daughter decided to hold it as a keepsake of that day. Georges survived the blast.

'The pictures are not about me anymore'

When Lebanon's civil disobedience campaign erupted on 17 October, Myriam Boulos went downtown to shoot it. The pictures that got most attention were shots of shirtless young men smashing plate glass windows and blocking roads with burning barricades.

The practice that produced those pictures was evident in Boulos' 2015 series Nightshift. These black-and-white photos are an atmospheric document of the culture of Lebanese 20-somethings partying in Beirut's industrial spaces. In the strongest pieces, Boulos' flash photography foregrounds the raw physicality of her subjects as they pose and perform.

Trained on the 17 October demonstrators, her flash captures the same visceral, performative energy.

Today Boulos, 28, distances herself from her 2015 series. She still characterises her work as a mix of documentary and personal research, but in the wake of the port blast she's changed how and why she shoots.

"In 2014, when I photographed Nightshift, I used photography … to question my place in Lebanese society. Now I use photography to defy or resist society in my own way.

"The pictures are not about me anymore," she says. "I'm too privileged for things to be about me at this point ... I wasn't wounded. I didn't lose a loved one. I didn't lose my house or a hand or an eye or a leg or whatever."

Where Boulos used to photograph people then get their details, she now feels compelled to listen to their stories before taking their pictures.

'The image is not the priority ... The documentation is more important'

- Myriam Boulos, photographer

"After the blast, the army became really awful" during demonstrations, she recalled, "so I left the front line and accompanied the wounded to the ambulance, to document the violence.

"With my flash it's really not respectful to take a picture of someone who's just been wounded. The flash is aggressive, so I'm not just gonna flash anyone who's just been shot and is vomiting blood."

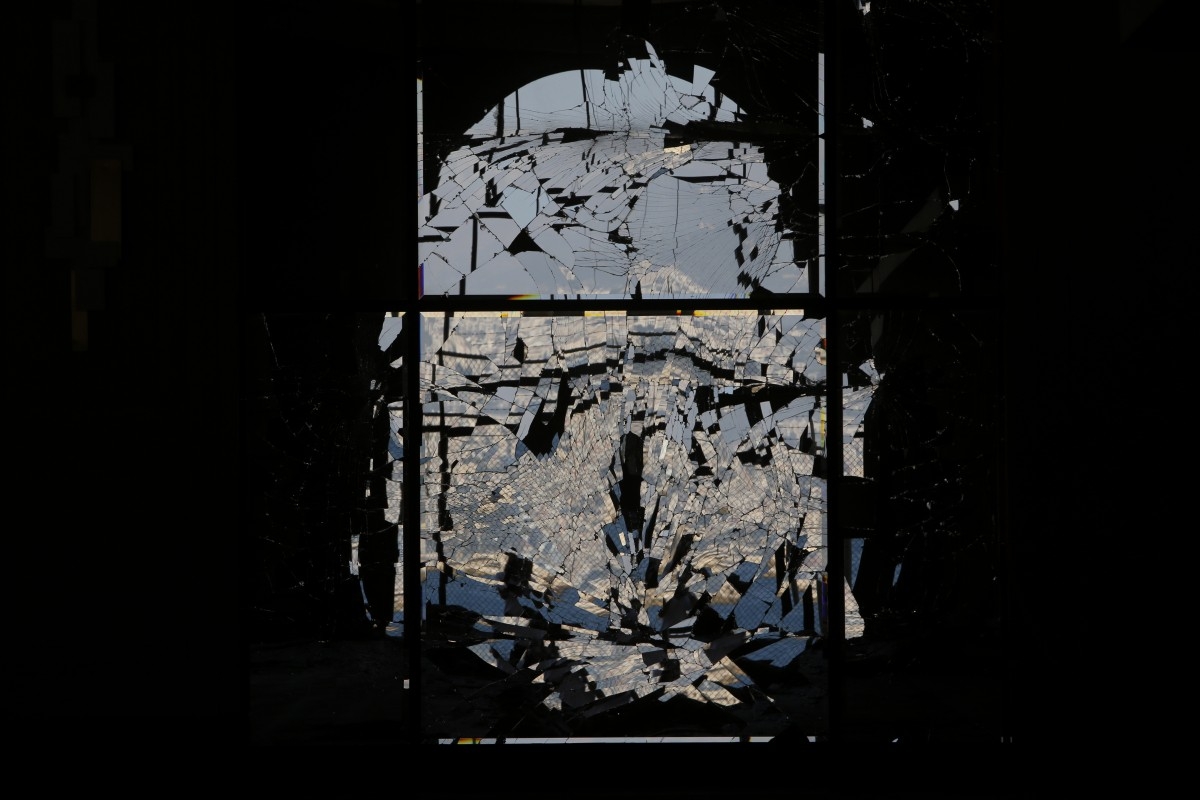

Boulos' post-blast photos - such as her portrait of Nour Saliba which was published in Time magazine, posing in her flat before a blown-out window overlooking the port - are shot at greater distance. As the documentary imperative has become more central, aesthetics are more peripheral.

It's "part of giving space to the person", she said, "and listening, and not needing to take something out of the person for my own needs or interests.

"The image is not the priority. It would be even better if the images were strong, but I'm not gonna hate myself for not making crazy strong images now ... The documentation is more important."

'It's about healing now'

Most of the photos in Vladimir Antaki's laptop files are preoccupied with the young volunteers who flooded into the historic port-side neighbourhoods of Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhail with brooms and shovels to join the clean-up - and those who went for other reasons - as well as the smashed façades and gutted interiors of houses.

'I think that I would have to document one place every day over a month to show how a building heals'

- Vladimir Antaki, photographer

"The city's getting fixed," smiled Antaki, 40. "It's crazy [two weeks after the explosion] you'd go some places and - it's not like nothing happened, but, wow. People are so dedicated, day and night trying to fix stuff, so people can go back to their houses.

"I think that I would have to document one place every day over a month to show how a building heals," he said. "It's about healing now, rather than the destruction."

Antaki's documentary photos stand in stark contrast to the work for which he may be best known, his 2017 series Beyrouth, Mon Amour, in which he electronically manipulated his pictures of building façades from rich and poor neighbourhoods around greater Beirut - mirroring and cutting them to create kaleidoscopic images resembling the non-figurative geometrical designs associated with classical Islamic art.

The bottom half of one of his post-blast landscapes is preoccupied by rubbish - a variegated assortment of plastic bags, cardboard boxes and takeaway food packaging, strewn amid a mound of glass shards. A unit of M-16-toting soldiers in camouflage fatigues file through the top half of the image, unconcerned with the clean-up.

Antaki, who is based in Beirut, and also spends time in Paris and Montreal, is considering abstracting some of his images of blasted Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhail façades, like his work in Beyrouth, Mon Amour.

"I think I'll do maybe five-to-ten special edition prints," he said. "The only thing is there's a human element in [these photos]. Most of the ones I did for Beyrouth, Mon Amour have no humans, just façades. It'll be interesting to see if I can create something out of those. It will take some time."

Feeling dismantled

The day before the blast, Maria Kassab travelled to Berlin for university. She joined the thousands of Lebanese who happened to have been overseas when some manmade disaster struck - held hostage to media and social media reports on a catastrophe from which chance has excluded them.

Kassab, 40, was a long-time resident of Sioufi, a few kilometres south of Beirut port, and several of her friends were forced to abandon their homes. After documenting Lebanon's civil disobedience campaign as an activist, she was now, in the weeks following the blast, unable to take photos or work.

'It’s hard to collect yourself in one place, especially when your work and your thoughts are politically involved'

- Maria Kassab, photographer

"All I wanted was to share, support, and voice out the tragedy," she said. "I found it incredibly difficult being away from my family and friends.

"Being away from the streets in a different city was emotionally and mentally troubling. It feels like living in a parallel world, partly here, and partly there. It's hard to collect yourself in one place, especially when your work and your thoughts are politically involved. You feel dismantled."

Kassab was working on several projects before the blast. Her 2019 series, Of Blasts and Illusions, works with black-and-white prints of figures from Lebanon's civil war years. To these she applies glitter, not to decorate the original form but to deface it, as if in an explosion. One untitled work, from December 2019, shows a couple standing on Beirut's seaside corniche, gazing out to sea with a child. Applied sparingly upon the three figures, the effect of the glitter is a remorseful erasure.

Using a decorative cosmetic to obliterate individuals in found photos is an ironic gesture fitting for a rarefied exhibition space. Its aesthetic is alien to that of those shooting the Beirut port blast.

Those who shot the aftermath of the 4 August blast tend to have their own trauma stories they feel compelled to relate.

Recollections of things they witnessed mingle in free association with snippets of conversations with survivors - with the firefighter who outlived his friends because he arrived late to the port, with the make-up artist whose hastily stitched hands had to be amputated days after the explosion.

When the focus shifts to his story, Marwan Tahtah navigates his way through memories of the explosion, of jumping on his bike to find the blast location, of arriving at the Électricité du Liban building to find a bloodied man, alone on the tarmac.

"He asked if I could put something behind his head," he recalled. "On the ground I found one of those pillows people wear when they fly. Ridiculous.

"They always ask, 'If you’re in an emergency situation, will you take photos or help?'" He blinked up from his coffee. "Of course you help."

Marwan Tahtah, Dalia Khamissy, Myriam Boulous, Maria Kassab and Vladimir Antaki were among the 17 photographers featured in Lebanon Then and Now, Photography from 2006 to 2020, a virtual exhibition curated by Chantale Fahmi and staged by Washington’s Middle East Institute between 13 July and 6 October 2020.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.