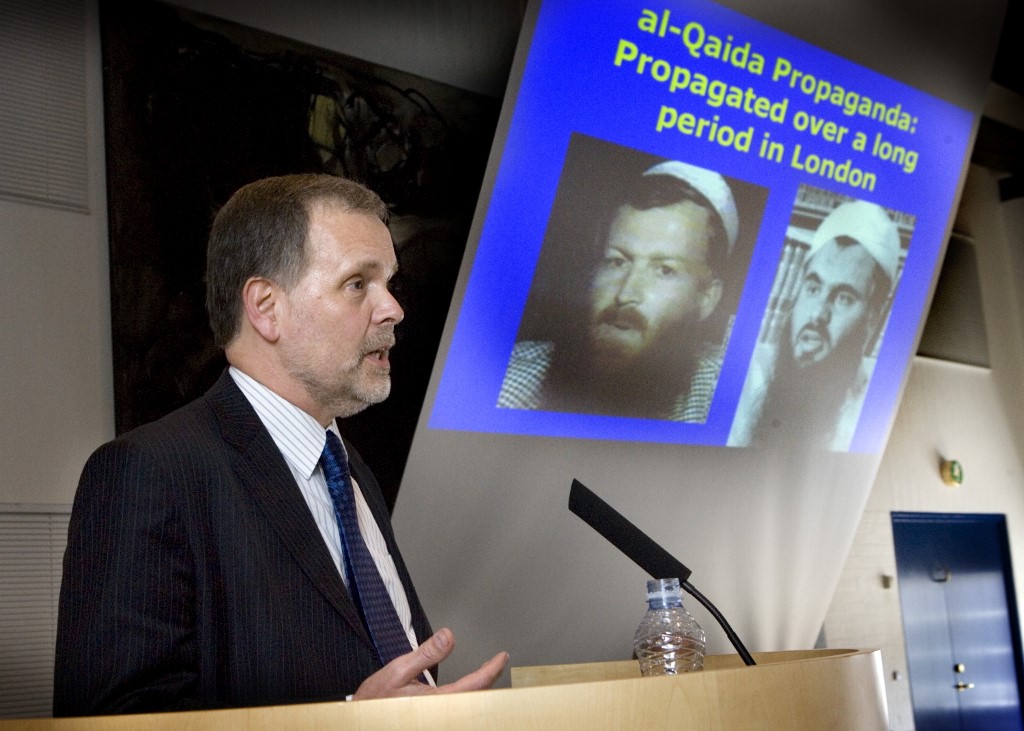

‘An honorary Muslim’: The police spy who monitored London's mosques in plain sight

One morning shortly after 9/11, with the remains of the Twin Towers still smouldering, thousands dead and missing and the world slowly accepting that many old certainties had vanished, two police officers met in a cafe across the road from London’s police headquarters at New Scotland Yard.

Both men were detectives with Special Branch - as the intelligence-gathering sections of British police forces are known - and both are said to have had long experience of counter-terrorism operations.

The al-Qaeda attacks had entirely dwarfed any plots that these men had encountered, however, and they must have realised that some of their previous investigations were looking somewhat trivial.

As they drank their coffees, the two men began to discuss plans to map London’s Muslim communities and organisations in a way that would enable them to gather intelligence about al-Qaeda’s influence within the city, and the risks that it posed.

At this time, Scotland Yard’s Special Branch was facing its own threat. Having already lost the lead role in tackling Irish republican militancy to the UK’s domestic security service, MI5, it was facing what amounted to a hostile takeover by the Yard’s Anti-Terrorist Branch, a unit which it had regarded as a rival for decades.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

In the new, post-9/11 world of policing, Special Branch needed to find a role for itself.

The two men in the cafe had between them many years of undercover experience, having infiltrated and spied upon many of the organisations they were investigating.

But they were aware that this was going to be all but impossible when it came to gathering information and spreading influence among London’s Muslim population.

One of the men, a detective inspector called Bob Lambert, suggested that they should operate in a way which would appear to be a more overt policing operation, drawing upon his experience of watching older Special Branch officers making contact with London’s Sikh communities following the 1985 bombing of an Air India flight over the Atlantic.

They decided they would set up an organisation that would come to be called the Muslim Contact Unit (MCU), and work collaboratively with leading Muslims, Islamic organisations and mosques, forming trust-based relationships in an attempt to counter the influence of al-Qaeda.

A calm man, a good listener and quick learner, Lambert would in time win the admiration of many of the Muslims he met - “he was regarded as an honorary Muslim,” recalls one - as well as the respect of senior security officials at the British government's Home Office.

Following his retirement in 2007, Lambert embarked on an academic career in the growing field of security studies and was rewarded with an official honour for “services to policing”.

But as they talked and drank their coffees, neither man could have predicted that the earlier undercover work of Lambert and other members of the MCU would eventually be exposed to public gaze; nor that this unmasking would cause widespread revulsion at the way in which they had performed their duties, trigger a seemingly endless series of compensation claims against Scotland Yard and result in government ministers ordering a public inquiry.

Moreover, once Lambert had been unmasked, a number of the Muslims who had cooperated with him would ask themselves whether his Muslim Contact Unit was all that it appeared to be.

‘The Hairies’

Much of Lambert’s professional life had been shaped by his undercover work. It began in 1983, when he joined a Special Branch unit that had originally been formed 15 years earlier, after anti-Vietnam War protests outside the US embassy in London turned unexpectedly violent.

Set up with the help of MI5, and officially known as the Special Demonstration Squad, the unit’s members had an unofficial nickname among those in the know at the Yard. As many of the male officers who joined it would grow long hair and often beards, they were known as “the Hairies”.

The rationale of the SDS was said to have been to provide intelligence on planned demonstrations that would help to prevent violent disorder. By the time Lambert joined the SDS, its officers had infiltrated a wide number of political groups, many of them focused on environmental issues and animal welfare.

Calling himself “Bob Robinson”, and claiming to be a vegan who worked as a gardener, Lambert soon became a regular figure at animal rights demonstrations.

With his long curls and boyish grin, he was a popular figure who regularly hosted parties at his flat in north London. He was useful too - he owned a van, and would ferry fellow activists to protests. He spoke at meetings and helped to compose pamphlets.

Soon he was at the heart of two organisations: a small anti-capitalist group called London Greenpeace, which had no relation to the larger campaign group with the same name, and another called the Animal Liberation Front.

“One day Bob wasn’t there,” recalls someone who thought of "Bob Robinson" as a friend and fellow activist. “And then Bob was there. He was everywhere.”

He was passionate, he was articulate, he was committed: nobody doubted Bob for a moment.

After four years - which is now known to have been the usual period of deployment for undercover SDS detectives - Bob announced to his London Greenpeace and ALF friends that he needed to lie low for a while: he believed the police were taking too close an interest in his activities.

A few people received postcards from Bob, posted in Spain, but none saw him again, for more than 20 years.

‘The Muslim desk’

No longer undercover, Lambert came back into the Yard, working with a Special Branch unit known as E Squad, which monitored suspected militant sympathisers in London. He is thought to have been stationed within a sub-unit then known informally at Special Branch as the Muslim desk.

He soon found himself back at the SDS, however, with the title of Controller of Operations, giving him responsibility for its day-to-day management.

Lambert appears to have been given enormous freedom. He took it upon himself to expand the work of the SDS across Britain, and decided that a change of name was in order to reflect the unit’s expanded role. SDS was said to now stand for the Special Duties Section.

He appears to have left his managerial role at the SDS behind some time before 9/11.

After that meeting at the cafe across the road from Scotland Yard, Lambert secured a small amount of funding, discreet office space on the second floor of a disused police building near London’s King’s Cross station, and the secondment of a small number of officers, at least a few of them from the Muslim desk.

The Muslim Contact Unit never had more than a dozen detectives, according to Home Office sources. Initially, none were Muslim, although a few Muslim detectives were later seconded to the unit.

Lambert would later claim that the cafe meeting was prompted not by 9/11, but by the launch of US air strikes against Taliban targets in Afghanistan the following month. He must, however, have been giving considerable thought before those air strikes to the ways in which Special Branch could help to counter al-Qaeda.

He also said that he was anxious to avoid past errors in counter-terrorism policing. “I remain stubbornly attached to error and claim complete responsibility for my own mistakes,” he would later write.

However, he then went on to state that the errors he had in mind were those made during Northern Ireland’s Troubles. He had “learned from mistakes in countering Irish republican terrorism”; police should have targeted terrorists, not political activists, and certainly not ordinary Irish Catholic communities, which he said “bore the brunt of stereotyping, profiling and stigmatisation”.

With the MCU up and running, Lambert says he set out to approach every mosque and Muslim association in the London area.

He also befriended a number of leading members of the Stop the War Coalition, a loose alliance of leftists, pacifists and Muslims that had formed in the weeks after 9/11. He was regularly to be seen on the Coalition’s marches, including one in February 2003, ahead of the US-led invasion of Iraq, that was the biggest protest ever held in the UK.

Many who met him at that time were quietly impressed. “I came to know Bob through the demonstrations that we held as the Muslim Association of Britain from 2002-3, and then the demonstrations regarding Palestine,” recalls Anas Altikriti, former president of the Muslim Association of Britain and the founder of the Cordoba Foundation, which aims to strengthen understanding between the Muslim world and the West.

“Up until 2005, he used to attend all of those demonstrations. I gathered he was there to check that things were going smoothly and to get to know a few people, and that didn’t surprise me.

“I found him to be a pleasant person, I found him to be courteous. I found him to be approachable. I found him to be someone who was keen to listen.”

“He was a really polite, gentle person,” says Azzam Tamimi, the British-Palestinian academic. Daud Abdullah of the Muslim Council of Britain recalls: “He could put you at ease, you felt easy in his company.”

It was not only Lambert’s demeanour that impressed - so too did his apparent willingness to engage with Muslims on the basis of their perspectives: he did not attempt to sell the positions of the British government or Scotland Yard to the people with whom he met and talked. And that gave some of them hope that he would, in turn, reflect those Muslim perspectives back to the Home Office.

Lambert later wrote that after his initial conversations he decided to attempt to remodel traditional community police methods in order to develop an innovative strand of counter-terrorism work.

“As head of the MCU… I helped form partnerships that empowered representatives of mosques and Muslim organisations against the influence of al-Qaeda propagandists, strategists and apologists in local communities in London.”

That is not quite how everyone at the Home Office would describe the work. “They recruited moderate extremists to counter the extremist extremists,” one senior official says bluntly.

Confronting Abu Hamza

Whatever the form of words used to describe the MCU’s efforts, the unit quickly notched up some remarkable successes.

At Brixton in south London, the MCU found a Salafi community - including many Black converts to Islam - that had been attempting to counter the influences of al-Qaeda propagandists for years before 9/11 and, indeed, long before the term al-Qaeda had gained any great currency.

Two men who had prayed at Brixton - Zacarias Moussaoui, who would later plead guilty to conspiracy to murder on 9/11, and Richard Reid, the would-be shoe bomber - had fallen under the influence of radical clerics who years earlier were ejected from the mosque.

Lambert and his MCU colleagues learned how the Brixton Salafis had countered the influence of these clerics through study circles or one-to-one counselling sessions. On one occasion, when one of the barred clerics, the charismatic Jamaica-born Abdullah al-Faisal, entered the mosque with dozens of supporters and attempted to speak, they resorted to the simple expedient of shutting down the public address system.

The MCU and the Brixton Salafis set up a company called Strategy to Reach, Empower and Educate Teenagers - Street Ltd - from offices near Brixton, to help foster such bottom-up initiatives to counter the influence of clerics such as Faisal.

On the other side of London, meanwhile, the MCU enjoyed even greater success.

The mosque at Finsbury Park in north London had fallen under the control of the Egyptian preacher Abu Hamza al-Masri. Following a police raid on the mosque in 2003, he had been preaching to hundreds in the streets outside.

In early 2005, the Muslim Association of Britain, with the support of the MCU and assistance from local police, MI5, the area’s MP, Jeremy Corbyn, and the office of London’s then-mayor, Ken Livingstone, was able to take control of the mosque from Abu Hamza and his supporters.

By this time, Lambert and his colleagues had reached an important perspective. “The MCU was at its strongest,” he later wrote, “when advocating the knowledge and skills of its Salafi and Islamist partners: street credibility; religious credibility; understanding al-Qaeda ideology; understanding al-Qaeda recruitment methodology; counselling skills; and commitment and bravery.”

The origins of Prevent

Around a year after Lambert’s meeting at the cafe across the road from New Scotland Yard, the British government’s newly-appointed chief security and intelligence co-ordinator, David Omand, began to redraw the country’s counter-terrorism strategy. Omand called it Contest, and would later say that this “was a name I literally dreamt up in the bath”.

Initially, according to Home Office sources, the greatest emphasis was placed on three of the four strands of Contest which Omand termed Protect, Prepare and Pursue.

Little attention is said to have been paid at that time to the fourth strand, known as Prevent, which Omand describes as an effort “to counter any attractiveness that [al-Qaeda’s] ideology might have for young people”.

Like the rest of Contest, the existence of the Prevent programme was not made public at that time: that did not happen until 2005.

Over the years, with its focus on Muslim communities and its growing determination - described in documents that were not intended to see the light of day - to bring about “attitudinal and behavioural change” among young British Muslims, the programme would come to be seen as deeply divisive.

What is the Prevent Strategy?

+ Show - HidePrevent is a programme within the British government's counter-terrorism strategy that aims to “safeguard and support those vulnerable to radicalisation, to stop them from becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism”.

It was publicly launched in the aftermath of the 2005 London bombings and was initially targeted squarely at Muslim communities, prompting continuing complaints of discrimination and concerns that the programme was being used to collect intelligence.

In 2011, Prevent's remit was expanded to cover all forms of extremism, defined by the government as “vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs.”

In 2015, the government introduced the Prevent Duty which requires public sector workers including doctors, teachers and even nursery staff to have “due regard to the need to prevent people being drawn into terrorism”.

A key element of Prevent is Channel, a programme that offers mentoring and support to people assessed to be at risk of becoming terrorists. Prevent referrals of some young children have proved contentious. 114 children under the age of 15 received Channel support in 2017/18.

Criticism of the Prevent Duty includes that it has had a “chilling effect” on free speech in classrooms and universities, and that it has turned public sector workers into informers who are expected to monitor pupils and patients for “signs of radicalisation”. Some critics have said that it may even be counter-productive.

Advocates argue that it is a form of safeguarding that has been effective in identifying and helping troubled individuals. They point to a growing number of far-right referrals as evidence that it is not discriminatory against Muslims.

In January 2019 the government bowed to pressure and announced that it would commission an independent review of Prevent. This was supposed to be completed by August 2020. After being forced to drop its first appointed reviewer, Lord Carlile, over his past advocacy for Prevent, it conceded that the review would be delayed.

In January 2021 it named William Shawcross as reviewer. Shawcross's appointment was also contentious and prompted many organisations to boycott the review. Further delays followed. Shawcross's review, calling for a renewed focus within Prevent on "the Islamist threat", was finally published in February 2023 - and immediately denounced by critics.

After the existence of the programme was revealed, British Muslims who engaged with Lambert and the MCU say these police officers were always at pains to present themselves as “anti-Prevent”.

That is not how the MCU’s role was seen within the Home Office, where the MCU was considered an integral part of the programme. There, officials say the unit’s “street empowerment” work was regarded, in Prevent’s early days, as one of its key components.

The MCU always remained under the control of Scotland Yard, but Lambert frequently attended meetings at the Home Office’s Whitehall headquarters.

There, he is said to have displayed a deep - and impressive - understanding of the structures of London’s Muslim communities, and of the beliefs of the Islamists and Salafis whom he sought to empower.

Privately, some senior officials at the Home Office compare the MCU’s work to Britain’s end-of-empire support for “moderates” within colonial independence movements, pitting them against “extremists”; or with official behind-the-scenes support for British socialists during the Cold War, in order to counter the influence of communists.

Some of Lambert’s comments at Home Office meetings caused eyebrows to be raised, however, not least when he described suicide bombings as “martyrdom operations”.

He seems to have been indulged, with some putting his language down to the deep immersion techniques he had drawn upon while serving as a police spy. Some jokingly asked each other whether Bob had “gone native”.

But a few people came to see him as a curiously insubstantial figure, one who readily absorbed some of the words and concepts of whatever world he happened to be delving into.

“I’ve no doubt he really believed everything he was saying,” says one official, “just as he really believed in animal rights when he was spying on the Animal Liberation Front.”

‘Lunacy at the Yard’

When it arrived, the backlash against the Muslim Contact Unit came from several directions at once.

From 2005, a number of right-of-centre think tanks, blogs and commentators began to question and then condemn partnerships of the sort pioneered by the MCU. Respected observers described the unit as “weird”, and headlines such as “Lunacy at the Yard” began to appear in the press.

The authors argued that attempts to prevent only violent extremism fell dangerously short of the mark; in order to save future generations of Muslims from radicalisation, the Prevent programme needed to combat “non-violent extremism” and to promote what were hailed as “British values”.

Meanwhile, October 2006 finally saw the hostile takeover that Lambert and his Special Branch colleagues had feared: the branch was merged with the Yard’s Anti-Terrorist Branch to form a new organisation called Counter-Terrorism Command.

Senior officers at the Yard commented that Special Branch had come to be seen as being “a bit too soft” at a time when the government said it was waging war on terror.

From then on, Muslim organisations who contacted Scotland Yard to ask for assistance with hate crime, for example, say they were sometimes sent an officer from the Prevent programme. If they asked to see someone else, it was likely to be a detective from Counter-Terrorism Command.

“The Muslim Contact Unit offered a valuable space for Muslims to interact with the police,” says Massoud Shadjareh, chair of the London-based Islamic Human Rights Commission. “And that space had shrunk.”

A week after the Yard’s merger, British government ministers announced that they would be seeking new partners among the country’s Muslim communities. This was the start of a process that eventually led to a number of the MCU’s collaborators being “declared outcast”, as Lambert would later put it.

The following year, having served as a police officer for 30 years, Lambert was able to retire on a full pension. One person who was invited to his retirement party recalls that he was much like most of the other people in the very large room: “A typical copper.”

So was this the real Bob? Or was it more method acting?

Academic pursuits

On retiring, Lambert began to forge an academic career at the universities of Exeter and St Andrews. Drawing upon his experiences with the MCU and London’s Muslim communities, he studied for a PhD.

He also set up a private company called Siraat Ltd, from an office in south London, a couple of hundred yards from the secret location from which his undercover Special Branch colleagues ran the Special Demonstration Squad.

Siraat - “path” in Arabic - stood for the Strategic Islamic Research Advice and Action Team. The company identified individuals who could be sent into prisons across Britain to mentor young Muslim inmates.

The attacks on the MCU’s methods and collaborations continued, however, with Lambert’s enemies pointing out that he had advocated “police negotiation leading to partnership with Muslim groups conventionally deemed to be subversive to democracy”. The MCU’s critics appeared to be on a roll, and the important caveat - “conventionally” - was of little consequence.

Those attacks culminated in a 2009 report entitled Choosing Our Friends Wisely, published by the Policy Exchange think tank. It is a report that is said to made a considerable impression upon the Conservative politician Theresa May, who within a few months would become home secretary.

Pressing on undaunted, Lambert turned his PhD thesis into a book, Countering al-Qaeda in London: Police and Muslims in Partnership. Curiously, the 402-page book makes no mention of Siraat.

It does contain a robust defence of his work with the MCU. “It was the identity of my Muslim partners that undermined it in the eyes of [his critics]," he writes. “If instead I had worked in partnership with Muslims who they deemed to be moderate and to be hostile to the Muslim Brotherhood - not connected to it - then they and their allies would not have sought to denigrate my work”.

In September 2011, the book was launched at the House of Commons. The event was hosted by Jeremy Corbyn, the Cordoba Foundation and the Council for Arab-British Understanding.

It was the highpoint of a policing and academic career that spanned 34 years.

It is no exaggeration to say that six weeks later, Lambert’s world - or worlds - would simply fall apart.

Breaking ‘the golden rule’

For years, Lambert had warned the SDS detectives whom he managed that they needed to keep a very low profile once their undercover deployment came to an end.

He wrote in one Special Branch document that the continuation of cover, post-deployment, was “the golden rule” of SDS tradecraft. And yet, as an academic, he was giving lectures, speaking at conferences, appearing on university websites.

The long curls had gone, and instead there was a greying beard. But he was instantly recognisable across the years. He was “Bob Robinson”.

One Saturday afternoon in October 2011, Lambert had just finished speaking at an anti-racism conference in London, when he was challenged by five of his old friends from London Greenpeace.

As the five began handing out leaflets headed “The Truth About Bob Lambert and His Special Branch Role”, he stepped down from the stage and slipped out of a side entrance.

He was followed down the street by a number of the London Greenpeace activists, who asked him if he would like to have a chat, or perhaps say sorry. He briskly walked away.

In an explanation that appeared briefly on the University of St Andrews website, Lambert said: “I can well understand that the passage of time will have done nothing to diminish their anger towards someone they believed was a trusted comrade but was in reality an undercover police officer.”

But from then on, more revelations about “Bob Robinson” came spilling out, each one more ugly than the last.

He is alleged in 1987 to have taken part in an Animal Liberation Front firebombing campaign, in which three branches of a department store chain, Debenhams, were attacked because they sold fur coats.

Two men were arrested - almost certainly on information provided by Lambert - prosecuted and jailed. One of these men says that the incendiary devices they used had been divided between three activists, and that “Robinson” was one of them.

The three set off for different stores, with “Robinson” assigned to one in Harrow, north west London. All three devices ignited, and the store at Harrow suffered £340,000-worth of damage.

Lambert has been accused in parliament of having been responsible for that attack. He denies the allegation, but does admit to having appeared in court on other charges under the name Robinson. And he has not yet explained how the firebomb that he is said to been given was later placed inside the store.

It emerged too that there had once been a real Bob Robinson. Mark Robert - “Bob” - Charles Robinson had passed away in October 1959 of a congenital heart defect. This Bob had been seven years old when he died.

He had been the only child of Joan and William Robinson, who died in 2009 and are buried in the same grave as their son. The headstone in the cemetery in Dorset, south west England, remembers them as “Mummy” and “Daddy”.

Lambert had stolen the dead boy’s identity. He had also carried out research on the boy’s family, and probably visited the grave and the area where he lived his short life.

There was nothing unusual about this within the SDS at that time. An SDS tradecraft manual, published by the inquiry into UK undercover policing in 2018, in advance of any public hearings, explained how SDS officers who were about to go undercover should acquire a copy of the birth certificate of what the manual describes as “an ex person”.

The manual then suggests that the SDS officer should establish the “respiratory status” of that person’s family, before going on to “assume squatter’s rights over the unfortunate’s identity for the next four years”.

It is a document that appears to ooze contempt for the people being spied upon, whom the Hairies invariably termed “wearies” - SDS jargon for activists whom they believed droned on about their political causes in a wearisome manner - as well as for the families of the dead children whose identities were being taken.

A parliamentary committee condemned the practice of stealing dead children’s identities as “abhorrent”.

But there was worse to come.

Intimate relationships

As “Bob Robinson”, Lambert had had intimate relationships with four of the women he had been spying on.

On being unmasked, he claimed to have fallen in love with the women, and apologised publicly to them. “They were fine upstanding citizens who really should not have had the misfortune to meet me,” he said.

His wife and two children, living in a small town north of London, had known nothing about these relationships. “I think, with hindsight, I could only begin to understand it by thinking about the immersion I had in my role. I think I probably became too immersed in my alter ego Bob Robinson. I think I probably lost contact with who I really was…”

One of the women with whom he had a relationship had borne his child, a boy born in 1985. After two years, “Bob Robinson” had suddenly vanished from the life of the boy and his mother.

In 2014, Scotland Yard paid the mother more than £400,000 to settle a claim she had brought. She has said that she feels as though she had been “raped by the state”.

In October 2020, the Yard paid substantial damages to Lambert’s son, who is said to have suffered psychiatric damage after discovering, at the age of 26, that his father had been an undercover detective spying on his mother.

These victims were far from alone. So far, more than 30 women have come forward to say that they were tricked into having relationships with SDS spies. Lambert was not the only undercover detective who fathered a child.

A number of those women have spoken publicly about the devastating impact that the police deception has had upon their lives. Many of them do not wish to be identified. The police spies’ wives are also devastated.

There was a “considerable overlap” between the SDS and the MCU, according to a well-placed Home Office source, who said that several undercover detectives joined Lambert’s Muslim liaison team.

At least one of these officers had intimate relations with several women he was spying on, under the cover name Jim Sutton, before joining the MCU.

His real name was Jim Boyling, and after Lambert retired from the police he helped to manage Siraat. Boyling is said by one person who knew him well to have also been involved with Street Ltd, where he is said to have used a false identity to pay the bills for its offices.

Mizan Rahman, a Muslim activist and poet who was the office manager at Siraat, recalls Lambert and Boyling as being “really good actors”, and particularly skilled at deflecting questions about their personal lives.

“If we asked questions about their wives or families, they would brush them away in a way that didn’t make you suspicious,” he recalls.

As a member of the MCU, Boyling is said to have travelled to Jordan, and to have also visited Israel shortly after a British suicide bomber, Asif Mohammed Hanif, murdered three people and injured more than 50 others at a Tel Aviv seafront bar, Mike’s Place, in April 2003.

Hamas later claimed responsibility for the attack.

A second would-be suicide bomber, Omar Khan Sharif, also British, vanished after his explosive belt failed to detonate. His body washed up on a Tel Aviv beach two weeks later.

There is reason to believe Boyling may have travelled to Israel with DNA samples taken from the attackers’ family members, while Sharif was missing.

On returning to the UK, he is said to have confided in a number of people that he had concluded that Sharif had been in Israeli custody before his body was discovered, but had made clear that he was not concerned to investigate his death.

Boyling’s past also came back to haunt him while he was serving with the MCU. One of the women with whom he had a relationship had spent years trying to find him after he walked out of her life, even spending several months searching for him in South Africa after a number of postcards arrived from there.

In November 2001, just weeks after Lambert had decided to set up the MCU, she traced him to an anonymous office alongside a bus station in south London, and sat in a pub across the road, watching the entrance.

Two days later “Jim Sutton” walked into the bookshop where she worked, several miles away, confessed that he had been a police spy, and professed his undying love. Within weeks she was pregnant, and shortly after that they married.

According to a statement made at the opening of the public inquiry into undercover policing inquiry, by a lawyer representing 22 of the deceived women, this was the start of “an increasingly abusive and controlling relationship”, which lasted almost a decade.

During this time, Boyling is said to have stopped his new wife from alerting her old activist acquaintances that their boyfriends may also have been undercover detectives. Steps were being taken, the public inquiry has heard, to prevent the wife of Boyling, the MCU officer, from exposing the activities of the SDS.

According to the statement made on behalf of the 22 women, many of their careers were upended, some were deceived into having children, others missed their chance to have children while in relationships with men they never knew to be police officers.

“All of the women, on discovering the truth, have had their personal histories, their sense of self and their ability to trust destroyed.”

‘Justice needs to be served’

Some of the Muslims who engaged with Lambert and the MCU were so appalled by the revelations that they cannot bring themselves to talk about the relationship they forged with him.

Anas Altikriti says: “When the story broke, I was one many who simply couldn’t believe what we were reading.”

He invited Lambert to a meeting, with several other people, where he confirmed that it was true. “I said Bob is there anything coming out and he said no. Adamantly he said no. And that turned out to be untrue.”

Some at the meeting, who had been criticised within their community for engaging so closely with the police “were quite agitated and angry and upset, believing they had been tricked into the relationship”.

Many London Muslims who had contact with Lambert broke it off immediately. One Muslim activist who had extensive contact with the MCU said his view at that time was: “There’s no way we can associate with Bob, and justice needs to be served.

“We didn’t see Bob as having done something bad with the MCU because of this, we thought – ‘you’ve done something in your past, and you haven’t dealt with it and now it’s caught up with you, you need to deal with it, and there needs to be justice’. I did speak to him about this, and he couldn’t say much, but I said I feel from my religious point of view, until justice has been done, I can’t work with you. And he understood that.”

Mizan Rahman says: “I’m glad I haven’t seen Bob Lambert since, because I don’t know how I would react.”

Amid the mounting scandal, Lambert was forced to resign a number of his academic posts and Boyling was dismissed from the police following a disciplinary hearing.

Boyling’s most serious offence, ironically, appears not to have been that he had tricked his targets into intimate relationships, but that he had then married one of them without informing his superiors, and disclosed to her a number of secrets from his undercover days.

Revelations about the SDS continue to emerge, not least through the public inquiry. That inquiry was ordered by Theresa May after a whistle-blower who had served in the unit revealed that it had mounted a surveillance operation against campaigners supporting the family of Stephen Lawrence, the victim of a notorious racist murder.

The Yard’s failure to properly investigate that murder had led to a previous inquiry concluding that police were guilty of what it termed “institutional racism”. And here they were, spying on the people who were campaigning to achieve the justice that they had failed to secure.

The new disclosures show that the SDS frequently targeted peaceful, law-abiding activists.

One undercover officer who used the cover name Lynn Watson – and was one of the few women to serve in the SDS – had danced around in public while dressed as a clown. Her task had been to infiltrate a street performance campaign group called the Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army.

Another undercover detective spent time building orange tanks out of plywood and cardboard after inveigling himself into a group campaigning against the arms trade.

In the aftermath of 9/11, when Bob Lambert and his colleague met for coffee across the road from Scotland Yard, they must have been almost painfully aware of the pressing need for Special Branch to start doing something to counter a real threat.

But one question about the Muslim Contact Unit remains unanswered, almost 20 years after that meeting.

Were its aims as described by Lambert: was it a trust-based community policing initiative, which aimed to engage with Muslims to counter the influence of al-Qaeda?

Or was the MCU, staffed as it was by surveillance experts, another espionage operation?

‘They were obviously eavesdropping’

One person recalls an intriguing encounter with the MCU at a mosque in west London, a couple of years after the unit was founded.

She and a colleague were there for a talk about Binyam Mohamed, the British resident who was at that time incarcerated at Guantanamo Bay, after being rendered from Pakistan via Morocco.

“We arrived early and sat alone in the mosque cafe. Two men came and sat at the next table. They were a white man with a beard and an Asian-looking man with a turban.

“The rest of the cafe was empty and they could have sat anywhere, but they sat right next to us. They were obviously eavesdropping on us.

“So we invited them to come and join us at our table. They introduced themselves as members of the Muslim Contact Unit, part of Special Branch. The bearded man explained that his name was Bob Lambert.”

Asked whether he thought the MCU was spying on the Muslims with whom it engaged, Daud Abdullah replies: “I wouldn’t rule it out.”

Abdullah was teaching Islamic studies at colleges in London. When MCU members enrolled as students, he wondered whether they were monitoring the course content and the students’ reactions.

And whenever he travelled abroad, his mobile phone often would ring, and the caller would say: “Hello Daud, Bob here…”

“I was unsure whether he was passing a message – that they knew I was travelling - or whether it was just a coincidence. It happened on several occasions.”

In response to a request made under freedom of information law, the Yard said it possessed no records about the MCU dating from the period when it was created, possibly because they had been “weeded” in line with its data retention and disposal policy.

However, internal Special Branch papers made available by the public inquiry into undercover policing include two documents that show clearly that at the time Lambert was openly befriending the leading lights of the Stop the War Coalition, his SDS colleagues were busy spying on them.

SDS officers also approached a number of women at protests against the impending invasion of Iraq in 2003, organised by the Stop the War Coalition.

One, calling himself Carlo Neri, is alleged to have proposed to the woman he targeted. She says she accepted and introduced him to her family as a prospective son-in-law. He too eventually upped and vanished.

In Countering al-Qaeda in London, Lambert is ambiguous about the extent to which the MCU was an intelligence-gathering operation.

He denies that it was, but at the same time writes admiringly of police officers who have been able deftly to reframe questions about whether community policing is a “double-edged tool”.

He also writes: “A commitment to the principles of community policing [is] more likely to produce good intelligence than its abandonment.”

Some Muslims who had dealings with the MCU are quite relaxed about the possibility of it having been an intelligence-gathering operation.

Altikriti says he assumed Lambert was gathering intelligence when first they met. “I wouldn’t be surprised if that wasn’t one of his objectives, during the times of the demonstrations and marches.

“I don’t think that that was the objective or the aim, of our encounters later on, particularly when they became more focused on the academic line. He was being attacked equally as we were.”

A Muslim activist who engaged with the MCU says he always pointed out to people that they were dealing with Special Branch. “I made clear to anyone who was going to talk to them that they were Special Branch, and the only role of Special Branch is to gather intelligence, so people knew everything they were saying was being recorded, and would be on a file somewhere.

“We’d say that in front of Bob and the others. I’d remind people ‘he is a very nice guy, but …’”

“It was useful for police to learn about the structure of Muslim communities and there is a legitimate need for Muslims to have some input into policing,” says Massoud Shadjerah.

“But we were not naive about the MCU as an intelligence-gathering operation. There was a lack of intelligence within the Metropolitan Police. Gaining that knowledge is not illegitimate in itself. What is a problem is when police look at communities only from the point of view of terrorism. That is problematic.”

And since the closure of the MCU, Shadjerah says, and the folding of Special Branch into the Counter-Terrorism Command, that happens far more frequently.

‘Learning from mistakes’

Bob Lambert remains proud of his work with the MCU.

In one of the few media interviews he gave, to Channel 4 News, he admitted that the relationships he had formed with the women he was spying upon had been “weak on my part … irresponsible”. When the interviewer put it to him that it had actually been cruel, he replied: “Yes, yes absolutely.”

He added: “Whatever is said, my reputation is never going to be redeemed for many people and I don’t think it should be. I think I made serious mistakes that I should regret and I always will do.

“The only real comfort I can take from my police career is the fact that the Muslim Contact Unit was about learning from mistakes.

“That unit was a genuine attempt to work with the Muslim community, Muslim individuals in London, to tackle al-Qaeda or the al-Qaeda threat in the aftermath of 9/11.”

Lambert declined to be interviewed by Middle East Eye.

Jim Boyling declined to answer questions, or comment on the allegations made about him at the undercover policing inquiry. In an email, his lawyer said: “Mr Boyling intends to provide his evidence to the Inquiry and in the circumstances it would be inappropriate to comment at this time.”

Inevitably, perhaps, questions may always linger around the method actors who moved from the Special Demonstration Squad to the Muslim Contact Unit.

Were they being sincere, when they entered their new role? Moreover, does that question really matter, if the work they did was worthwhile?

The MCU appears to have been quietly closed down in 2016, several years after the SDS was closed. By that time, however, another undercover policing unit, the National Public Order Intelligence Unit, had already been created.

Meanwhile, many of the undercover officers of the SDS have yet to be identified, including most of those who later joined the MCU. Some have been granted anonymity by the public inquiry.

There may well be women across Britain who do not know that the men they loved had been spying on them; Muslims who do not know that that the police officers who earnestly befriended them and sought to earn their trust had previously been engaged in manipulation, and abuse, and lies.

Photo: The sign outside New Scotland Yard is reflected outside the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police in central London on 4 March, 2014 (Reuters)

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.