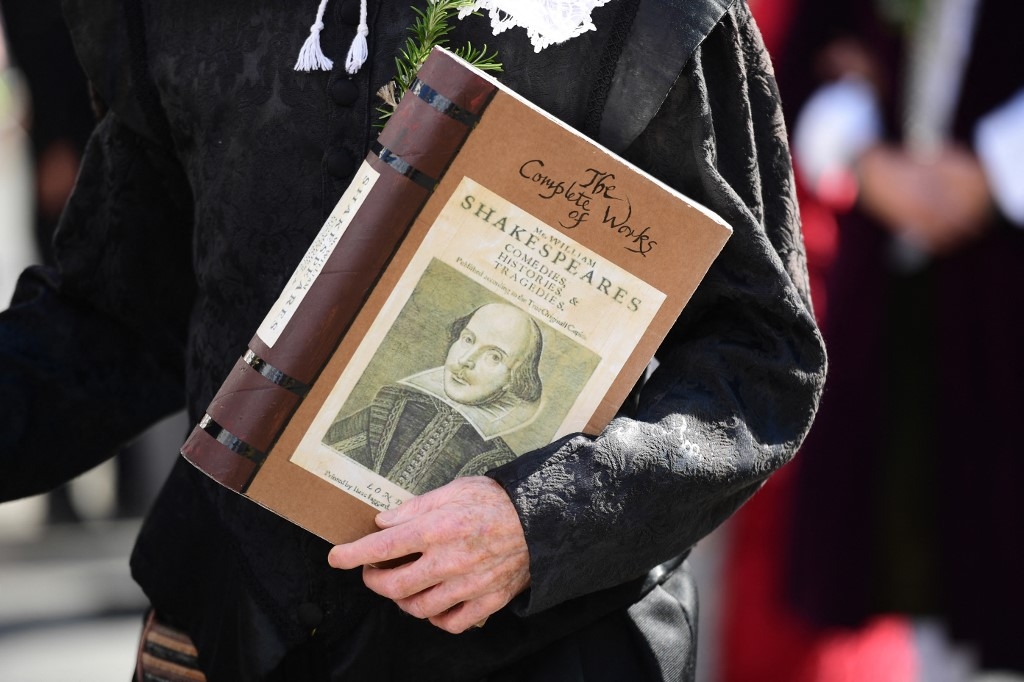

How Shakespeare's works challenge colonialism

Lucrece, at the moment of her death, raped by the last Roman king, Tarquin, and having stabbed herself to rid herself of the shame, says “like a late-sack’d island, vastly stood / Bare and unpeopled in this fearful flood.”

Conquest as rape is perhaps one of the most cliched tropes. In the above lines from The Rape of Lucrece, however, Shakespeare goes beyond the cliche: the reference to “late-sacked islands” serves to ground the audience in their contemporary reality vis-a-vis the Caribbean islands and other colonial territories (where colonial Spain reigned supreme, but where England had interests and designs).

These details can be easily construed as the fulfilment of a colonial fantasy, or as a potent commentary on the perils of colonialism

Conversely, the metaphor situates colonialism within a Greco-Roman paradigm, revived by the Renaissance, that necessitates tragic punishment for acts of excess, transgression and tyranny, such as the rape of Lucrece - or, by extension of the metaphor, colonialism. Indeed, the epic poem observes the rules of Greco-Roman tragedy, and Tarquin’s hubris is punished by an uprising of the nobles and the populace, which not only brings about his downfall, but also drives the entire Tarquin dynasty out of Rome, abolishes the monarchy, and establishes the Roman Republic.

Likened to an act of transgression that is not only morally deplorable, but also dooms its perpetrator and his whole dynasty, colonialism does not appear in a flattering light.

The allusion to colonialism in The Rape of Lucrece is hardly anti-colonial: the coloniser remains centred and the colonised are generally silenced - only to speak metaphorically from the standpoint of the victimised, raped and dying woman. The establishment of any sustained critique of colonialism requires reading too much into the metaphor. It does, however, show a lack of enthusiasm for the colonial project, upon which we can build our own decolonial reading of Shakespeare.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Today marks the 405th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. It comes amid a growing interest in recent years to address questions of race and colonialism in Shakespeare’s texts, both theoretically and in performance.

Creative visions

The Shakespearean oeuvre presents an invitation for selective and creative interpretation. Shakespeare’s plays were blueprints for performances, demanding directorial decisions, including which themes and interpretations would be at the core of spectators’ experiences, and which would be relegated to the margins.

This is especially the case with The Tempest, a play Shakespeare wrote when nearing his retirement. It also happens to be a play in which colonial themes are dominant; it has since lent itself to various postcolonial commentaries and appropriations. It is through The Tempest that we can reconstruct Shakespeare’s relationship to the colonial project, and start to imagine a decolonial (if not necessarily anti-colonial) Shakespeare.

Shakespeare sets The Tempest in a southern Mediterranean island that is also vaguely American-Caribbean. The protagonist, Prospero, the former Duke of Milan, settles on this island along with his daughter, Miranda, after a conspiracy by his brother Antonio and the king of Naples forces him to flee Europe and sail southwards.

Using science and magic powers, Prospero drives away the island’s former sovereign, the Algerian witch Sycorax, who leaves behind her son, Caliban. Prospero’s agenda for Caliban first comprises the undertaking of a civilising mission, as Prospero and Miranda proceed to teach Caliban language. Savage that he is, Caliban makes a sexual pass at Miranda, which marks the termination and failure of the mission to civilise him.

In response, Prospero enslaves Caliban. The other inhabitant of the island is Ariel, a spirit who Sycorax imprisoned in the bark of a tree. Prospero proceeds to free Ariel and bind him in his service. A running undercurrent throughout the play is both Ariel and Caliban seeking freedom: the first through excelling in his service so that his master would grant him his freedom as a prize, and the second through a series of largely misguided and failed rebellions.

These details can be easily construed as the fulfilment of a colonial fantasy, or as a potent commentary on the perils of colonialism; it is the latter that I choose to emphasise (spoilers ahead).

Freedom high-day

The colonised is anything but silent throughout the play; when taunted by Prospero and Miranda, Caliban taunts back: “You taught me language, and my profit on’t / Is I know how to curse. The red plague rid you / For learning me your language.”

On the eve of his rebellion, Caliban chants: “No more dams I’ll make for fish / Nor fetch in firing at requiring / Nor scrape trenchering, nor wash dish / ‘Ban ‘ban Ca-Caliban has a new master, get a new man. Freedom, high-day, high-day, freedom, freedom high-day; freedom."

Prospero’s island is not a happy place. Through magic, Prospero becomes an omniscient and omnipotent figure that controls all aspects of life on his island: the utopian settings of the play are disrupted from the start by Prospero’s excessive control, rendering the play dystopic, and making everyone on the island miserable.

This includes Prospero himself. Throughout the play, and despite his omnipotence, Prospero appears irritable, conflicted, obsessive and possessive. This continues to be the case, especially as Prospero manages to cast his former enemies ashore his island: nearing revenge exacerbates rather than resolves Prospero’s inner conflict.

Up until the play’s final scene, it seems as if Prospero, through excessive control and the drive for revenge, maybe walking the same line of tragic hubris that Tarquin walked. It is only in the final scene that Prospero finds peace, when he decides to forgive his enemies, let go of his magical powers, give up his sovereignty over the island, and return to Milan. “And thence retire me to my Milan, where / Every third thought shall be my grave.” His final words to the audience, in the prologue, sound almost like a penance: “As you from crimes would pardoned be, / Let your indulgence set me free.”

Settler utopia

This came at a time when proto-Zionist narratives that imagined the deliverance of the oppressed through colonisation were taking form, and as English Puritans embarked on the Mayflower journey, inaugurating this fantasy of colonial deliverance into practice.

Shakespeare’s Prospero is clearly the forerunner of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, who in turn presents the prototype of the colonial man who flees oppression in Europe and creates his own dominion on a faraway island. The Tempest in many ways references the budding genre of utopian writings, which was inseparable from the colonial imagination of the Americas. It anticipates future settler utopias, where utopian socialists would seek to colonise the Americas to create their putative perfect societies there.

And yet, against this running motif of deliverance through colonisation, Shakespeare presents redemption in dismantling the colony, renouncing attempts to control the universe and returning to Europe. All this is not enough to claim Shakespeare as a decolonial or postcolonial (let alone anti-colonial) figure. It is just the start.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.