UN aid chief in Turkey says Syrians in Idlib won't be abandoned

Millions of people living in northwest Syria face a nerve-wracking wait amid fears Russia could block a new United Nations resolution authorising the continued delivery of essential humanitarian aid into the war-torn country’s last opposition-held territory.

Mark Cutts, UN deputy regional humanitarian coordinator for the Syria crisis, told MEE that those dependent on aid would not be abandoned, but other aid workers warned of potentially disastrous consequences if supplies into Idlib and other areas are disrupted by a Russian veto.

UN Security Council resolutions in place since 2014 have enabled the world body’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) to coordinate the regular delivery of food, medical supplies, including Covid-19 vaccinations, and other necessities into the region from Turkey.

Resolutions have been renewed annually or biannually. But there are concerns that Russia, the Syrian government’s key military ally, could use its veto as a permanent member of the Security Council when the current resolution expires on 10 July. Moscow wants aid instead to be delivered through Syrian government-held territory.

The UN Security Council is due to vote on a new resolution, proposed by the US, Ireland and Norway, on Thursday.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

According to UN figures, 4.4 million people live in opposition-held northwest Syria, which covers Idlib province and surrounding areas, and the north of Aleppo province. Prior to Syria’s near-decade-long war, the population of the region was just 1.5 million people.

Many of them fled from areas of the country now back under Syrian government control. Northwest Syria is divided into areas controlled by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, a hardline militant group, and Turkish-backed Syrian rebels.

'Catastrophic need'

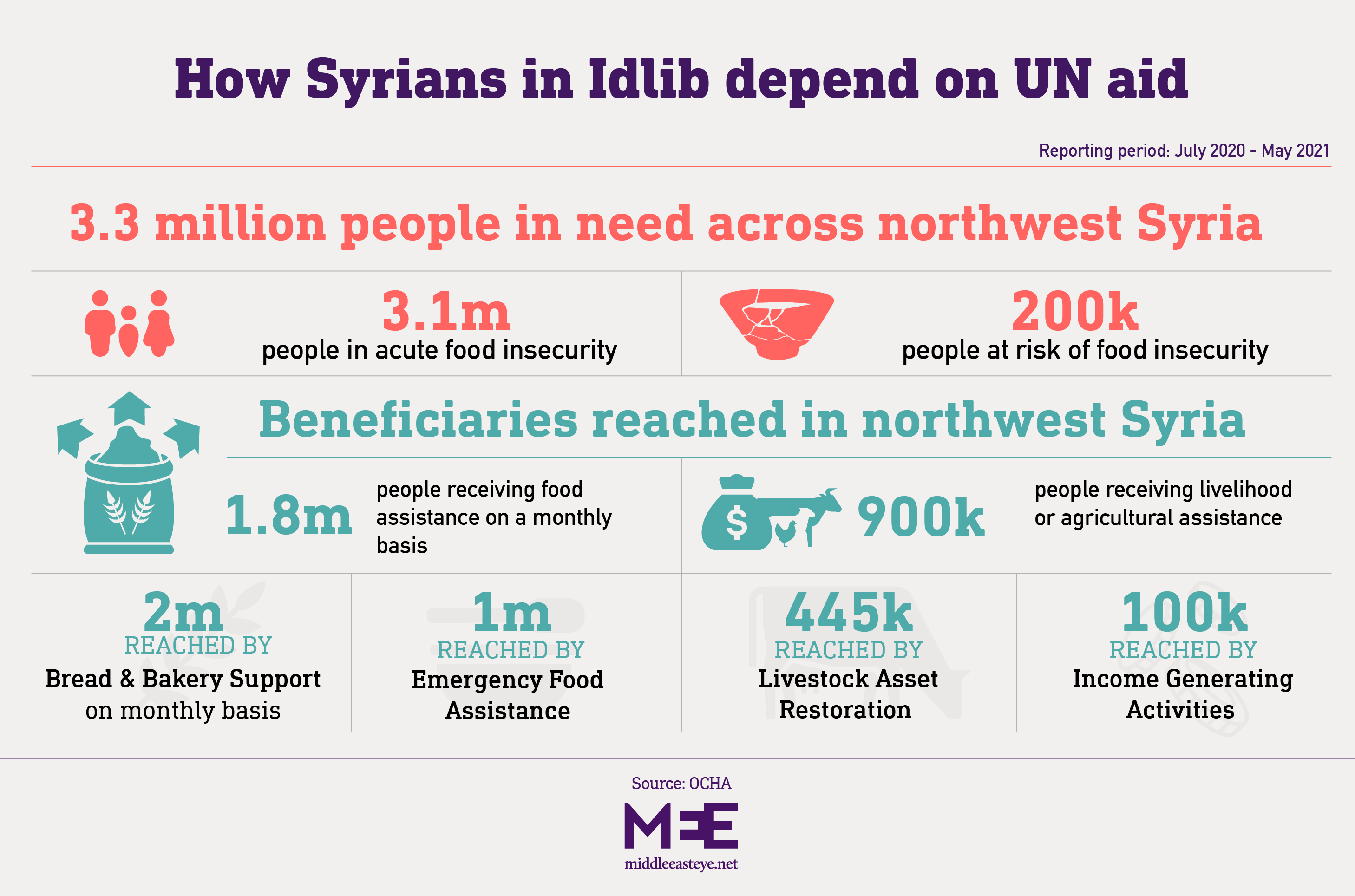

About 2.8 million people live in camps for displaced people and about 1.9 million people are “in extreme and catastrophic need.” At least three million people in the region directly depend on aid for their basic needs, with about 2.5 million of those supported through the UN programme.

Cutts told MEE that OCHA currently sends about 1,000 aid trucks through Syria’s Bab al-Hawa border crossing each month.

“Some of the most vulnerable people in the world live in this region,” said Cutts, speaking in Gaziantep where OCHA has its regional base.

“They don’t have what they need for their survival. They depend heavily on humanitarian aid just to survive.”

Sundous Jamo, an advocacy officer at Horan Foundation, a local NGO that partners with the UN, told MEE that the situation in Idlib had been made worse by the collapse in value of the Syrian lira in the past two years, in part due to the impact of US sanctions targeting the government in Damascus.

She fears shortages caused by a veto could cause prices to skyrocket again, with many people dependent on UN food packages even for staples such as pasta, lentils and rice.

“It will be a disaster, if the UN cuts aid,” she said.

Zubeyir Berk, programmes coordination manager at the Humanitarian Relief Foundation (IHH), also fears that hundreds of thousands of people will fall into life-threatening hunger without continued UN support.

The Turkish aid NGO estimates that 400,000 people face hunger-related deaths unless food aid continues to reach them.

“The people are so desperate that they need a package of pasta, and if the UN aid is cut, they’ll have nothing to eat,” Berk told MEE.

“There is drought this year. They can’t grow anything. We supply even bread since they are unable to harvest wheat for making bread.”

Russian veto

Concerns about the consequences of a Russian veto have grown since Moscow, along with China, last year vetoed resolutions allowing the delivery of UN aid through two other border crossings at Bab al-Salam and al-Yarubiyah. Since then, UN aid has been delivered only through Bab al-Hawa, known as Cilvegozu on the Turkish side.

“Russia wants to help the Syrian government recover as much of Syria as possible,” Aron Lund, a Syria specialist at the Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI), told MEE via email.

Russia argues that the situation in Syria has changed as the Syrian government has regained territory, and that the delivery of aid from within the country is now possible.

It points out that HTS, which contains factions formerly affiliated with al-Qaeda, is listed by the UN and many countries as a terrorist organisation. It says that OCHA has no presence in Idlib and has no way of controlling how its aid is distributed, or determining its “final beneficiaries”.

Cutts told MEE the UN has created a sophisticated monitoring mechanism to ensure that aid does not fall into the “wrong hands”.

“We do very careful monitoring. We are very confident that UN aid goes to the people who need it. We have multiple ways to check it,” he said.

'Weaponising aid'

Jamo, of the Horan Foundation, told MEE that the presence of HTS in Idlib did not mean that the humanitarian crisis facing millions of people could be ignored.

“HTS’s presence has nothing to do with the humanitarian job. It is obvious that we help people who need this aid,” she said.

She accused Russia of “weaponising humanitarian aid for its political agenda”.

An NGO worker in Gaziantep, who asked to remain anonymous due to the sensitivities around the issue, told MEE he believed Russia planned to use its veto to put pressure on the UN to work with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s government, and to use aid as a means to bolster the Syrian economy in government-held areas.

“Russia wants to restore Assad’s legitimacy. However, while doing so, Moscow doesn’t want to spend money,” he said.

“Diverting humanitarian aid to the regime-held areas is a strategy to revive the collapsed Syrian economy, given the fact that the UN partners with hundreds of NGOs, purchases necessary materials from locals, employs thousands of people.”

Cutts asserted that the UN would continue to work with all the parties to the conflict to find ways to increase humanitarian access.

But he said: “The only way you can deliver aid across an active frontline is if you have an agreement with the parties to the conflict on both sides. But last month we saw an escalation in hostilities.”

He also underlined that most of the people in northwest Syria dependent on monthly UN aid live in camps that are situated close to the Turkish border.

Berk, of IHH, said it would be impossible for NGOs to sustain current levels of aid without UN support.

“These people need acute humanitarian aid. If the UN stops funding NGOs and coordinating the aid delivery, it is very unlikely that NGOs can overcome [the loss of] such a large-scale and multidimensional aid organisation,” he said.

Asked what would happen if Russia did veto a resolution sanctioning OCHA’s work, Cutts said: “We will not abandon millions of people. Basic humanitarian principles will still apply with or without the resolution. International humanitarian law and human rights law must be respected,” without elaborating further.

However, according to a contingency document shared among NGOs working in Gaziantep and seen by MEE, two solutions have been proposed.

Either international NGOs will lead the humanitarian aid delivery, or the UN’s World Food Programme will buy aid and donate it to NGOs for delivery into Syria. According to the document, NGOs expect cross-border aid deliveries to continue regularly until at least mid-October even if Russia vetoes a new resolution.

Turkey, meanwhile, has called for the aid operation to continue. Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu last week met his Russian counterpart Sergei Lavrov in the Turkish resort of Antalya.

Speaking afterwards, he said Ankara was in talks with Moscow and other members of the UN Security Council in regard to a new resolution.

Feridun Sinirlioglu, Turkey’s ambassador at the UN, has also warned that a veto would lead to a humanitarian crisis and “would simply permit the regime and terrorist organisations to increase their campaign of murder to an even higher scale”.

Lund told MEE that while Moscow could use its power of veto as a threat he did not think it wanted to stop all UN aid operations into opposition-held areas because doing so would create potential problems with Turkey.

Russia and Turkey signed a Memorandum of Understanding in 2018 to create de-escalation zones in Idlib and maintain relative calm in the region. Although bilateral relations were damaged after pro-Syrian government forces killed 33 Turkish soldiers in 2020, the two countries have largely refrained from clashing over Syria.

Still, Lund said, the risk of the UN stepping back as an organiser and coordinator of the aid effort would bring more trouble to the region.

“Even if donor governments increase the support to NGOs working in Syria, losing the UN’s cross-border role will have a very, very dramatic impact,” he said.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.