Coerced into silence: The reality of being a Palestinian doctor in an Israeli hospital

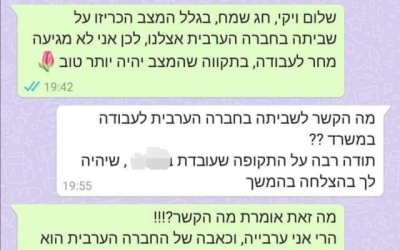

In May, during Israel's war on Gaza, I was inundated with messages from fellow Palestinian physicians working in Israeli hospitals. They faced a pressing dilemma.

On the one hand, they wanted to take part in the national strike, declared on 18 May by the Arab High Follow-Up Committee, as a protest against Israel’s war on Gaza, the attacks on al-Aqsa Mosque and the ethnic cleansing of East Jerusalem, with its dispossession of Palestinian families.

They are only too aware of the watchful eyes of their Jewish Israeli colleagues and bosses, who have conditioned them to become apolitical subjects

On the other hand, they are only too aware of the watchful eyes of their Jewish Israeli colleagues and bosses, who have conditioned them to become apolitical subjects, cautious and domesticated employees. These worries proved justified, as some hospital directors issued a statement saying that any employee who participated in the strike would be punished.

Accordingly, not only do Palestinian physicians always show up for work in Israeli hospitals, they also have to take centre-stage in the ceremony launched whenever Israel declares war on Gaza. Palestinian and Jewish staff hold signs with slogans saying “Peace”, “We choose life” or “Arab and Jews refuse to be enemies”. These hospitals and institutions come to be celebrated as lighthouses of coexistence, floating islands of sanity.

Political and diminishing

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Though seemingly naive and optimistic, these slogans are particularly misleading. They suggest that Palestinians resisting ethnic cleansing choose war rather than coexistence. More, that the Israeli settlers and armed forces that protect them have also chosen war, in contrast to the Israeli physicians, who appear to have chosen peace. It portrays Palestinians in Lod or Haifa protecting their streets and houses, and angry Jewish supremacist mobs that chant “Death to Arabs”, as two extremist sides. They also imply that the status quo before recent events was just and harmonious.

These coexistence ceremonies, and their exhalation in the Israeli and international media, portray the hospital as a neutral and apolitical space, rather than one which fully embraces Zionism's ethos and rituals. A case in point is the fact that, while these performances assuage the conscience of Jewish-Israeli physicians as acts transcending politics, they are highly political and diminishing to the Palestinian staff.

Palestinian citizens of Israel represent a large percentage of the healthcare workforce. It is among the few areas of work that offer job security for Palestinians in Israel. When I was growing up in my little hometown in the Galilee, it was clear that if I could not find a secure job in the healthcare field, I would face great difficulties in a racist job market. Currently, almost 21 percent of physicians and 23 percent of nurses in Israeli hospitals are Palestinian citizens of Israel. But this does not make these workplaces immune to the structural and institutional racism of the Israeli state and society.

As a Palestinian, learning to accept racist structures is a part of studying medicine and working in an Israeli hospital. Starting from studying in a university built on stolen land with no acknowledgment, to being expected to stand at graduation for the national anthem that excludes you by definition, and having to stand annually for a moment of grief on the fallen Israeli soldiers in 1948 - soldiers who were fighting to displace your people.

Adaptation for survival

These are just a few of the experiences. However, just like African Americans, Black South Africans and other oppressed peoples, individuals learn to adapt and manoeuvre their way in order to climb up the ladder. This should in no way be seen as a sign of progress: it is a critical part of human adaptation for survival.

We cannot continue to uncritically celebrate Israeli hospitals as “islands of sanity” simply because Palestinians and Israelis work there together. Palestinians and Israelis also work together in the factories in West Bank settlements, and study together in Ariel University in the illegal settlement of Ariel, and even collaborate within the Israeli army. Their shared workspace does not make these places beacons of hope.

Other models of existence for indigenous and marginalised communities do exist, as I have learned during my public health fellowship in the United States.

Brave scholars, activists and physicians have forced universities to recognise the stolen land they stand on and work to decolonise their curriculums. Physicians and scholars have shifted the discussion to clearly target structural racism as a public health hazard and are working to dismantle it. They have framed police brutality as a public health problem and initiatives such as White Coats for Black Lives” or Equal Health - Campaign Against Racism flourish and help us redefine the practice of medicine.

These are the types of coexistence ceremonies we should encourage and applaud; the ones that commit to a joint struggle against oppression rather than offering shallow symbols of hope that may make us feel better, but do nothing to alter a dangerous and painful status quo.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.