Elbouma: Egypt's feminist band fighting misogyny through music

For some cultures, owls are figures of wisdom, magic, or the occult. In Egypt, the bird is heavy with connotations of bad luck, ill will, and moody women. Most commonly, a bouma - or an owl - is what women are derisively called when they frown, complain, or – god forbid – are feminists.

Point out the latent sexual harassment in a beloved Egyptian comedy, and “don’t be such an owl” is a quick retort in patriarchy’s back pocket.

Egyptian sister duo Marina and Mariam Samir, together known as Elbouma [Owl], have found pride in the word. “Owls prey on animals larger than themselves,” Marina tells Middle East Eye. “As feminists, I feel like we do the same thing.

"We’re trying to fight something that’s a lot bigger than ourselves, something that’s all around us, that’s embedded so deeply into everything, including ourselves.”

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

First launched in 2014 as Bent El Masarwa, translated from the Arabic as “daughter of the Egyptians”, the band’s eponymous album sought to represent the realities and struggles of being a woman in Egypt, as well as open the door for feminist music production in the country.

Over the fours years since 2017, and following multiple features in international media and a crowdfunding campaign to finance their next album, the band’s membership changed, as did Mariam and Marina's approach to feminist music production, prompting the rebrand into ElBouma.

The new album, Mazghuna, is a powerful story in nine tracks. The ideas, themes, and lyrics were sourced from three storytelling workshops for women in Upper Egypt.

The album title itself is based on the old name for the village where ElBouma held its first storytelling workshop, Abu Ghreir in the Upper Egyptian city of Minya. According to the workshop participants, the name is also a reference to the word mazghuda, i.e. a woman who has been prodded into silence.

The result is a rich album with a unified sound, but with just enough dexterity to cover a range of topics, from child marriage to racism to the power of women’s circles, without feeling jarring.

FGM and other feminist fights

Buffeted between what has been called a “botched #MeToo moment”, attempts to further curtail women’s legal rights, and what seems to be an endless social media fight for a host of demands including justice for sexual assault survivors, Egyptian feminists don’t often get to rejoice in something as bright - and as affirming - as an album like Mazghuna, dedicated to them.

Some of the themes are familiar feminist fights, including FGM, which 87 percent of Egyptian women between the ages of 15 and 49 have undergone, according to the most recent data in the 2014 Egypt Demographic and Health Survey.

But even that harrowing practice is tackled in a refreshingly nuanced manner in the album’s third track, Astek Ya Astek (Elastic, Oh Elastic). Juxtaposing a playful melody with grotesque lyrics, the song details not only the gore of the pseudo-medical practice, but also how its effect stays with a woman’s body and psyche.

The song haunts in layers of parody:

Gather the scalpels and snip away,

And let her red blood drip,

over a piece of white cloth.

Oh mother of the “pure” circumcised girl,

Snuff out the candles ten times,

Give them coffee instead of sharbat.

While perhaps not as recognisably feminist as Astek Ya Astek, one of the most poignant tracks on the album is Al Barr (On the Shore), which explores a common but often uncomfortable conversation.

Formed around a metaphor of sailors stuck on shore, the tear-jerking song explores Egyptian mother-daughter relationships. It acknowledges mothers as both victims to social mores and their enforcers, prisoners themselves and prison guards to their daughters, the boat carrying a weight across the water and the anchor holding it to shore. But the song can't answer what comes next: forgiveness, defiance, or an uneasy resignation to the way things are.

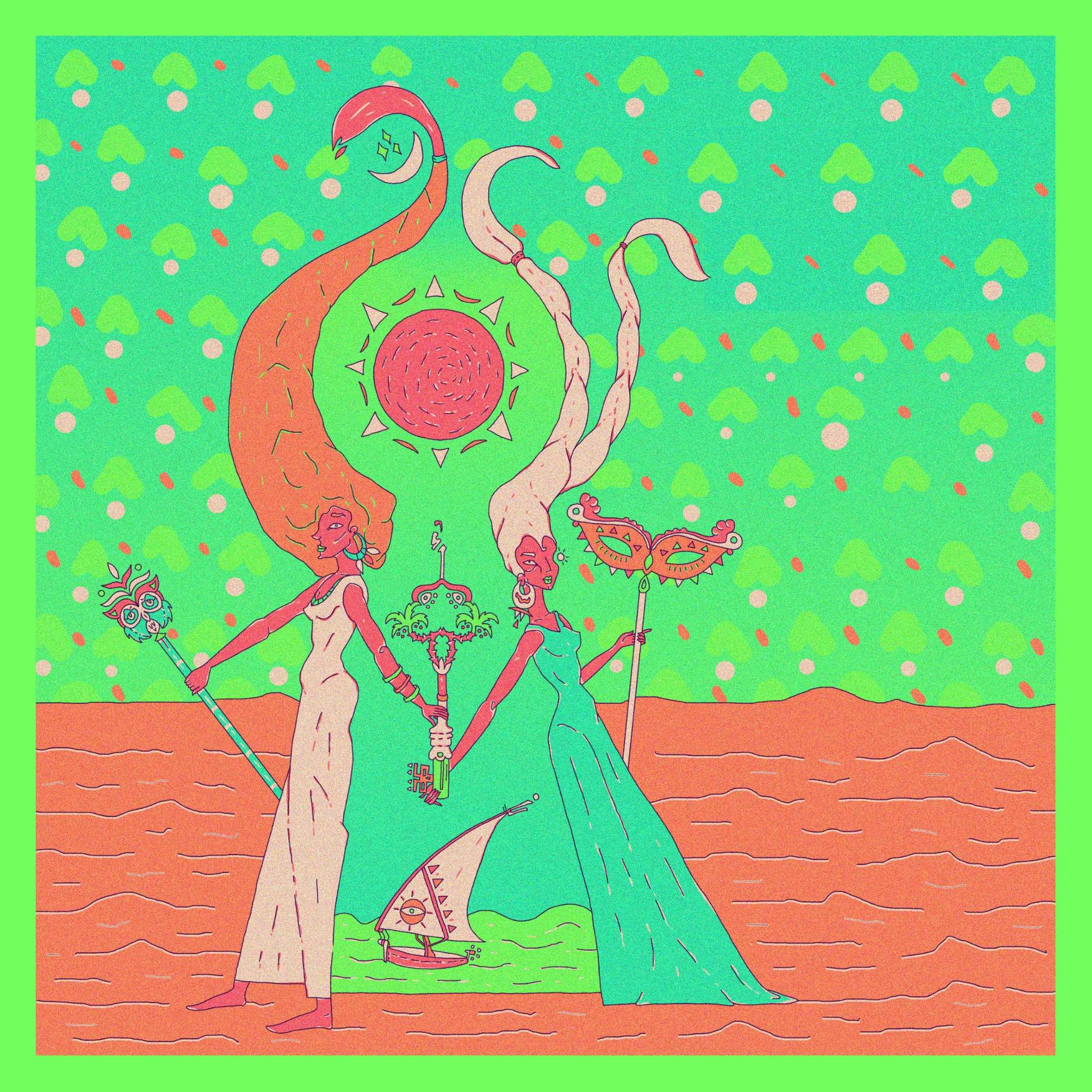

Each song is accompanied by an illustration on the cover sleeve by Egyptian artist Aliaa Ali. In the album’s signature green, orange, and fuchsia palette, the eight artworks are dynamic complements to the music.

In Al Barr’s illustration, a daughter reaches for the sky, one foot padlocked, while the other is stuck inside the quagmire of her mother, who in turn is contained within her own mother. All three women are both weighed down and rising, each with a heart-shaped padlock dangling from their body.

A deeply-rooted Egyptian sound

The ease with which the album moves between moods is due to Mariam Samir and producer Ramy al-Majdoub’s approach to the music, which defies easy categorisation. The album is deeply steeped in folklore, both sonically and lyrically.

The lyrics are heavily symbolic, featuring the banks of the Nile, boatmen on the water, the roots of palm trees, and jasmine flowers on a string

Songs like Ya Arousa (Oh, Bride) and Astek Ya Astek (Elastic, Oh Elastic) – which discuss child marriage and female genital mutilation (FGM), respectively – lift directly from traditional Egyptian folk songs.

Yet the sound also veers into electronic, ambient, shaabi, and even spoken word.

The lyrics, by singer-songwriters Esraa Saleh and Marina Samir, as well as workshop participant Marwa Hassan, are heavily symbolic, featuring the banks of the Nile, boatmen on the water, the roots of palm trees, and jasmine flowers on a string.

They paint pictures that are grounded in Egyptian culture, without feeling claustrophobically specific.

For some tracks, the singer, either Mariam or Marina, sings alone. In others, we hear a chorus of women singing, humming, or chanting in unison, to hypnotising effect. Kont Fakra (I had thought), written by Aswan workshop participant Marwa Hassan, talks about the racism women from Aswan (who tend to be darker-skinned) face when they venture out of their city.

“I thought I was free,” chants a chorus of women, and it sounds like a microphone has been placed in the middle of the storytelling circle.

The listener is brought into the cipher, surrounded by the entrancing recitation, with Mariam’s shiver-inducing classically trained soprano in the background.

Storytelling circles in Upper Egypt

Part of what it meant for the team to produce a feminist album is to look outside of Cairo, which is usually overrepresented as the be-all-and-end-all of Egyptian experiences. “It was important that everything is a collective creation,” says Marina.

“We wanted to get outside of ourselves, to look past our own experiences as Cairene women in the middle class, with particular circumstances that have defined both our consciousness and our feminism.”

Between August 2016 and February 2017, the band facilitated three workshops in Upper Egypt. In Abu Ghreir in Minya, Deir Drunka in Assiut, and Aswan, 34 women joined for week-long workshops. For three days, the band facilitated storytelling circles, which were followed by three days of writing and composing.

To avoid harassment for performing songs that might be seen to offend conservative values, the whole group decided to take the stage wearing the same dresses, donning the same masks

At the end of every workshop, the band would host an open concert where everyone in the community was invited to listen to early demos of the songs. Every time, they would invite the participants from the workshop to sing with them on stage.

It was only in Aswan that the women were enthusiastic to perform, with a precaution to protect against possible backlash.

To avoid harassment for performing songs that might be seen to offend conservative values, the whole group decided to take the stage wearing the same dresses, donning the same masks, so no one would know who’s who.

“This might be the first time I wear a mask you can see…But how many thousand times have I worn a mask you’ve loved, while we talked or greeted or made plans,” goes El Sellem El Moussiqui (The Musical Scale), the remarkably bright eighth track on the album, about the childlike joy of singing on stage together.

Though Mariam finds it nearly impossible to pick a favourite song from the album, she says the moment that El Sellem El Moussiqui captures - the energy of singing with everyone on stage - has stayed with her the most.

Marina, on the other hand, points to her favourite in a heartbeat: Ya Arousa (Oh Bride).

Based on the experiences of participants in the Assiut workshop in 2016, the album’s second track opens on a zaffa, the traditional wedding procession popular in Egyptian marriage ceremonies. There’s a wedding and all the sounds of joy that comes with it, but already, the words are muffled. Throughout the song, both music and lyrics become progressively distorted, as the song takes an ever more upsetting turn.

In the same trance-inducing chant as Kont Fakra, with a haunted quality to the supposedly joyful zaffa, they sing:

They put you in a wedding dress,

and stuffed the dress to make it fit your tiny body.

Dolls, toy horses, and marbles will be part of her dowry.

Isolate her behind a wall,

and raise it inch,

by inch,

by inch.

“It highlights a paradox that I find very important,” Marina tells Middle East Eye. “How the happiness of a wedding can be the facade that hides so much misery.

"And even though the song talks about being a child bride, which isn’t something I’ve experienced, I can relate to the idea of how marriage and family as an institution can cause so many women so much misery. The worst expression of it is girls who get married as children, but it’s not the only one.”

An echo in the dark

Though a lot of the album is gentle – often deceptively so – Mazghuna is not always easy listening, an intentional choice the duo made going in. ‘Al Wesh Banet (It Shows on Your Face) starts off the album with a pleasant, lilting melody that barely lasts half a song before the dissonance starts. Tones become grating over a piece of spoken word, and it’s quite difficult to listen to, especially with headphones.

'Whenever we’d go somewhere to get mixing and mastering done, they’d try to turn us into a pop song'

- Mariam Samir, Elbouma singer

The choice to place this song first is an explicit one, to set the tone for the album. The song, according to Mariam and Marina, reflects a sense of frustration, but goes a step further and actually brings the listener into the experience.

“Whenever we’d go somewhere to get mixing and mastering done, they’d try to turn us into a pop song,” Mariam says. “But we’re not, and we don’t care about the sound coming out precisely ‘right’, or pure. We care that it comes out sounding expressive and full and real, more than anything else.”

“There are things we know are grating,” she adds. “But I’m fine with being a little frustrating, I’m glad I have that space. What it means to me that this is a feminist album has a lot to do with what voice I allow to come out of me, as I’m making decisions for the music. What’s the sound you allow to exist? Is it pitch perfect, or is it expressive?”

Before the band received funding from FRIDA, the Young Feminist Fund, they launched an Indiegogo crowdfunding campaign to produce the album in the fall of 2017. A question was raised by some in activist circles: why should this piece of art be a feminist priority? In the sequence of legal battles, sexual assault and abuse cases, and notoriously rampant sexual harassment, why is this album important?

“Music might not change everything,” says Marina. “But the way I see it, someone can wake up one day feeling alone, like no one goes through what she does, and just stumbles upon a song on Soundcloud, and finds an echo of her own voice.

“I think that is the first thing that change can stem from, us finding each other."

Mazghuna often feels like calling out for each other in the dark, and finding – like in the album’s seventh track 7 Follat (7 Jasmine Flowers) – our own words coming back to us in the voice of another.

Exploring that sense of affinity, the familiar voice chants:

My sadness recurring

in other girls’ stories

Stock up on jasmine flowers

Six, seven jasmine flowers…In venting or in crying,

the seven jasmine flowers join together.

Mazghouna is available on You Tube and Soundcloud

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.