Can Iraq's prime minister win re-election and curb the power of Iran-backed militias?

Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi has been on a media blitz in recent weeks, urging Iraqis to get out in large numbers to vote in the upcoming October 10 parliamentary elections.

"In a few days, Iraqis will decide their future by participating in the elections," he wrote on Twitter last week. "Don't trust fake promises, and don't listen to threats and intimidation. Defeat them with your votes, in free and fair elections."

The following day, Iraqi Kurdistan President Nechirvan Barzani echoed his remarks, saying "the majoritarian mentality, establishing militias, crippling institutions and sectarian hegemony, threatening civil war" were not ways to make a stable Iraq.

The statements were implicit references to the powerful Iran-backed Shia militias that operate under the umbrella of the state-sanctioned Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF).

Militias have immense political power in Iraq - they are well-armed with arsenals of ever-more sophisticated rockets and, more recently, drones.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Their growing military power augments long-standing fears that they could potentially outgun the Iraqi military.

Kadhimi and Barzani's statements seemingly indicate that a large turnout will be crucial for curbing the power of these militias and preventing them from further undermining and weakening the state.

"Prime Minister Kadhimi is sending out explicit messages to the public urging them to vote against militia-backed lists in the upcoming elections," Ceng Sagnic, a Washington DC-based political analyst of Kurdish and Middle East affairs, told Middle East Eye.

"However, these messages serve a different cause than gaining more support for Kadhimi himself - which would be an attempt in vain - but get him more support from the international community that he is willing to benefit from after his term comes to an end," he said.

"In other words, Kadhimi is investing in his post-premiership career."

In recent years, Iraqi prime ministers have been selected by consensus among militia groups and political blocs to prevent the ascendence of any strong leader with popular public support.

This process came about after former Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi tried to win the 2018 elections by combining his support from the US with his popular support among the Iraqi public.

"Kadhimi, much like his predecessor, Adil Abdul-Mahdi, were carefully proposed by militia groups despite knowing their anti-militia opinions, as part of a policy of maintaining weaker government authority," Sagnic said.

The analyst said this approach would continue after the upcoming poll and again delay the formation of a new cabinet.

'A consensus figure'

To date, Kadhimi's premiership has had few victories.

"The only success that can be counted for the premiership of Kadhimi is improved relations with the Kurdistan region's leadership and the support he gained from the international community for his rhetoric about strengthening state institutions," Sagnic said.

"But, as a matter of fact, he lacked the power to take any concrete steps to address the actors that undermine the central Iraqi government."

Kyle Orton, an independent Middle East analyst, also doubts Kadhimi can make any fundamental changes.

"Within the confines of his position, Kadhimi has done a moderate amount to win back power for his office from Iran, but the practical difference is marginal and the task is hopeless," Orton told MEE.

"Kadhimi's messaging is clearly intended to draw away votes from the militiamen in parliament, and perhaps he will succeed - there is clearly growing revulsion at their conduct.

"That said, the October elections cannot make much of a difference: where it counts - in the security forces, in the ministries, on the streets - Iran's militias control what they need, and this factor is the overriding one when it comes to Kadhimi's foreign policy," he said.

Nicholas Heras, senior analyst and program head for State Resilience and Fragility at the New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy, said Kadhimi "is looked at as a sort of last, best hope for Iraq to back away from being totally dominated by Iran".

"Iran has strong influence over Iraq, and that has been true for years, but the wider sentiment among the Sunni Arab states in the Middle East is that an Iraq that is totally dominated by Iran is unacceptable and deserves no external support," Heras told MEE.

"For that reason, Kadhimi has emerged as an important consensus figure for foreign actors who see him as an acceptable leader for a complicated country, and one who is not totally beholden to Iran."

However, Kadhimi lacks a political base, added Heras, and "has to borrow his base from other Iraqi leaders". As a result, the Iraqi prime minister finds himself "in a constant state of cobbling together allies. His allies are locked in a political death match with the Iran-backed bloc led by [Iran-backed Badr Organization leader] Hadi al-Ameri, and if his allies have a poor electoral showing, Kadhimi is done as prime minister".

"He is not a great mover and shaker, which is why the protest movement and the movement for reform has been disappointed by him, and he is not in a position to risk outright civil war within the Shiite community in Iraq if he acts too strongly against the Iran-backed Hashd Shaabi [PMF] militias," Heras added.

"But Kadhimi is a vehicle for foreign support into Iraq, especially the United States, which is his principal draw for his allies."

Heras described the October 10 vote as "an inflection point" that will play a role in determining whether Iraq ultimately "either moves irreversibly into the Iranian coalition or remains a contested place but with access to support from the United States and its partners".

Counterbalance to Tehran?

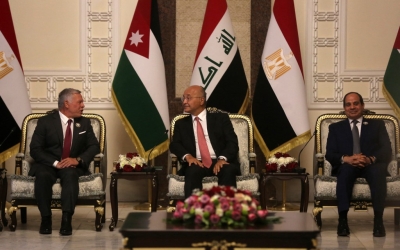

Under Kadhimi's short premiership, Iraq has hosted negotiations between regional rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia and started talks on a new tripartite economic and political partnership with Egypt and Jordan.

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi visited Baghdad in June, marking the first visit by an Egyptian leader in more than 30 years.

While these expanding economic and political ties with other Arab countries could, over time, lessen Iraq's economic dependency on Iran, they are unlikely to provide a counterbalance to Iran's extensive influence.

"Iran's influence over Iraq cannot be countered with any regional relations or tripartite agreements that can only be used for economic gains," Sagnic said.

"The most significant aspect of Iran's power in Iraq stems from its deep involvement within the security apparatuses, including but not limited to Shia militias," he added. "Potential economic gains from Prime Minister Kadhimi's celebrated initiatives with regional countries may even be appreciated by Iran, as Tehran greatly benefits from the Iraqi economy, mostly from the funds that are allocated for militias."

While Iraq is the host country for negotiations between Iran and Saudi Arabia, that doesn't make it a power broker, nor should those negotiations be thought of as an Iraqi initiative, Sagnic noted.

"The US government under Joe Biden is anticipated to reduce its involvement in Middle Eastern crises, which inevitably forces Arab Gulf states to seek alternative policies," he said.

"The most prominent of these alternative policies have been the reconciliation with Qatar in order to unify the Gulf front, and direct negotiations with Iran. Saudi Arabia selected Iraq as a suitable platform for these negotiations, assuming Iran would not refuse to use Iraq for this purpose instead of giving the credit to another Arab country outside Tehran's sphere of influence," he added.

Orton also doubts the emergent Egypt-Iraq-Jordan tripartite partnership could effectively challenge Tehran's sway over Iraq.

"The Iran-Saudi interaction playing through Iraq is Kadhimi making a virtue of necessity - and with some panache, give him credit - but any relations with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, or Jordan will be allowed to go only so far as they do not threaten vital Iranian interests, which is to say ultimate control of the state," he said.

"If the idea is that Iraq can invite in the influence of [Sunni] Arab states to counter Iran's dominance in Baghdad, that is a non-starter; the Iranians do not want such an outcome and they have the ability to stop it."

Sagnic also sees another political motive behind Barzani's recent references to the militias.

"There are serious allegations that Nechirvan Barzani is preparing to nominate himself for the presidency of Iraq," he said. "The primary reason for the proliferation of Iraq-focused statements by

him is likely to be related to such aspirations."

Consequently, like all other nominees, Barzani's statements "highlighting stronger state institutions and unity aim at capitalising on the growing anti-militia sentiments among ordinary Iraqis and certain strong political blocs in Baghdad".

"The October elections bear a significance for the forthcoming government and the president, but statements addressing the elections should not be confused with concrete steps for limiting the influence of Iranian-backed militias on Iraq," Sagnic said.

"There are currently no signs of any political steps or a consensus to diminish the power of militias, as all nominees and political groups will go back to negotiations with militia leaders after the elections."

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.