Abdulrazak Gurnah: Nobel Prize repaid my faith in a vital writer of our times

In 1967, an 18-year-old boy and his older brother set off from Zanzibar. They were fleeing the cruelties and barbarities of a terror state that tortured and imprisoned people. It was a state that shut down schools and curtailed lives; that had learned its techniques from East Germany.

The only way to escape was to use fake papers, which meant that the boys could not return to see their family for many years.

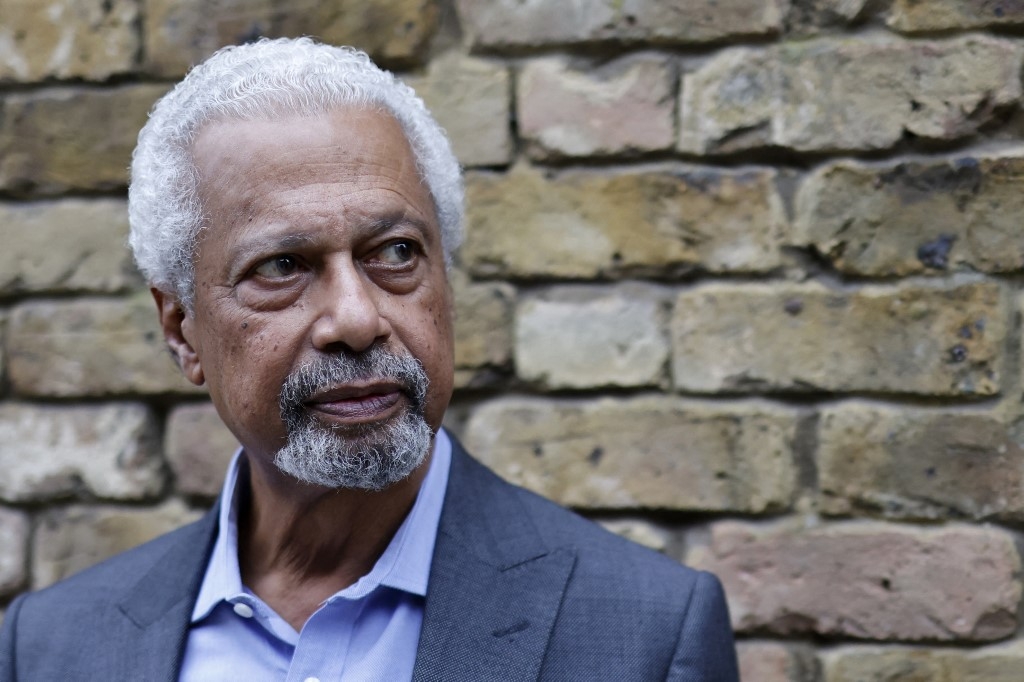

The England that the young Abdulrazak Gurnah arrived in was cold and unwelcoming, its people openly hostile. Gurnah recalls people casually saying terrible things to his face without understanding the hurt they were causing.

Gurnah’s writing has a clarity and a quietness and a tone that is like a piece of music in an unusual key. It is as if every word is deliberately, carefully placed there

He pursued the education denied him in Zanzibar and as well as studying for a PhD, he began writing fiction. Gurnah's first language is Swahili, but he wrote in English - he was reading in that language and the connection between reading and writing is intimate and powerful.

English is an elastic and inventive language, one which can be stretched and continually remade. As Gurnah has said, it is no longer the language of the colonial power, it belongs to everyone.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Gurnah’s writing has a clarity and a quietness and a tone that is like a piece of music in an unusual key. It is as if every word is deliberately, carefully placed there.

Finding forgotten pieces of history

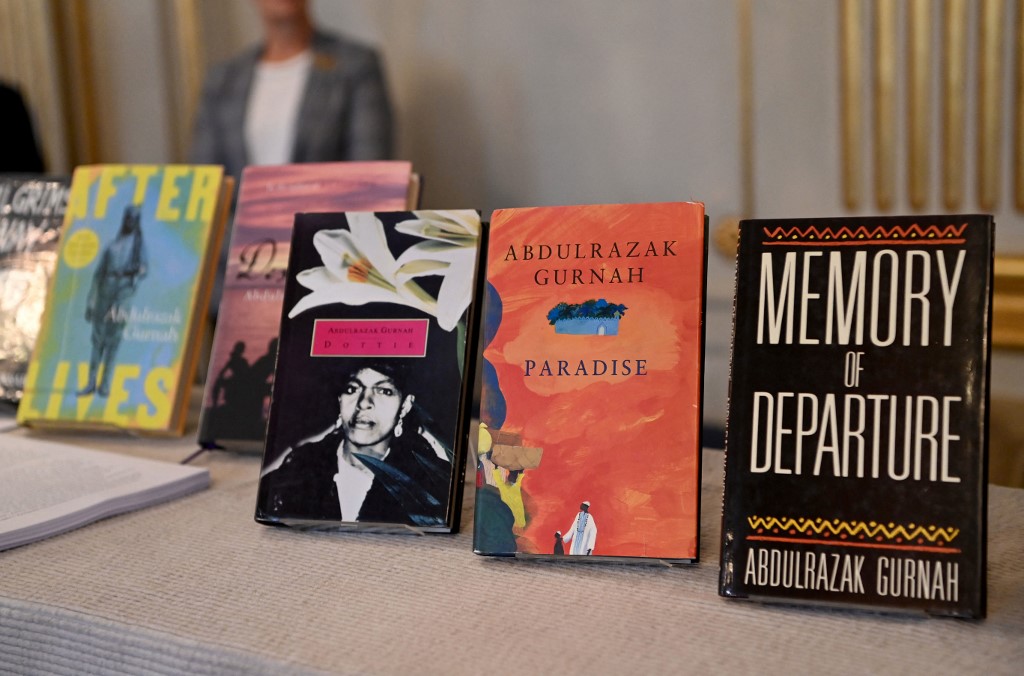

Gurnah is deliberate, too, in looking at the complexities of the pre- and post-colonial world. He examines the slavery that existed before European colonisation. He finds forgotten pieces of history. In his most recent novel, Afterlives, he explores the barbarity of German colonisation and how it brutalised the lives of men and women in East Africa during and after the First World War.

I am a publisher and I met Gurnah in 2001, when I read the manuscript of his sixth book, By the Sea. I had recently joined Bloomsbury Publishing as editor-in-chief and By the Sea was one of my early commissions.

In the opening pages were these words: "I am a refugee, an asylum-seeker. These are not simple words, even if habit of hearing them makes them seem so."

His exploration of the meaning of these words in his 10 novels - the plight of refugees and asylum seekers - are themes that inhabit all of Gurnah’s writing. His work has always spoken to me. His characters are displaced from their homes - refugees from war and the trauma of colonialism - but they are also blown across the world through the forces of trade, economics, politics - and love.

I have long been attracted to such stories. As a young teenager, I read Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. As a student, I wrote about the effects of colonisation on the work of Achebe and Joseph Conrad.

But perhaps I was also drawn to these stories because my maternal ancestors, pre-Babylonian Berber Jews from Oufrane in Morocco, had been blown, like Gurnah’s characters, across deserts, in caravans, between Timbuktu and Mogador (now Essaouira). Then, on the outbreak of the Second World War, those same winds took my 16-year-old mother on the last boat from Morocco to Britain.

Stories we need to hear

When Gurnah came to Bloomsbury, he had been shortlisted for the Booker Prize for his earlier novel, Paradise. Every one of Gurnah’s novels had received admiring reviews.

He has consistently been significant in the study of post-colonial literature. But it can be difficult to take on a writer of middle age in mid-career, and most especially a writer of such quiet subtlety as Gurnah. It is natural that the press, the trade, publishers and readers want the young and the new and the splashy.

I wanted more for him than good reviews. His novels are remarkable for the quality of the writing, the importance of their themes, and for the beauty and complexity of the tales they tell. They are stories we need to hear and I wanted significant sales - and prizes - for this author.

Our credo at Bloomsbury has always been "to publish authors, not books", by which we mean that we want to be there for the author through thick and thin.

This kind of publishing relationship is like a long marriage and, as in any marriage, there are highs and lows, happiness and disappointments. To be a good publisher you need to be stoical and optimistic - and not frightened of failure.

For every successful book, there are many that never find the audience they deserve. Publishing is a very subjective business. Publishers may try to predict a market for a book but, in the end, all that editors have is their own taste.

The best editors learn to believe in their taste while trying to balance the forces of commerce. And they need to have the courage to stick by their authors.

'Hope seeps away'

When I received the manuscript of Afterlives, I thought: this is it, this is the moment I have been waiting for. It is one of his very finest novels. We were in the middle of a new refugee crisis, and Black Lives Matter was about to happen. I saw that the chair of the Booker Prize for that year was the most distinguished of Britain’s black publishers, someone who would know Gurnah’s work, and so I decided to pull his publication forward a month, making it eligible for the prize in 2021.

I was sure it would at the least get on the longlist. But I was wrong. I made my bet and lost. For the first time in two decades of publishing this writer I loved and admired, I felt defeated.

As with all great literature, his novels will help us understand and make sense of this world we live in. Perhaps they may also help bring about change

On 3 October this year, the Guardian published an article where renowned black writers chose books that have been overlooked. There was no mention of Gurnah.

On social media, I wrote: "After 20 years of publishing him and keeping the faith that his time will come, hope begins to seep away."

Four days later, to my astonishment, Gurnah won the most important prize of all: the Nobel Prize in Literature. It was the greatest happiness of my professional life. Speaking after the prize, Gurnah commented that although "the world is changing and our perceptions are changing… institutions are just as mean and just as authoritarian as they were".

His work will now be translated into dozens of languages and read the world over. Institutions may be the same, but, as with all great literature, his novels will help us understand and make sense of this world we live in.

Perhaps they may also help bring about change.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.