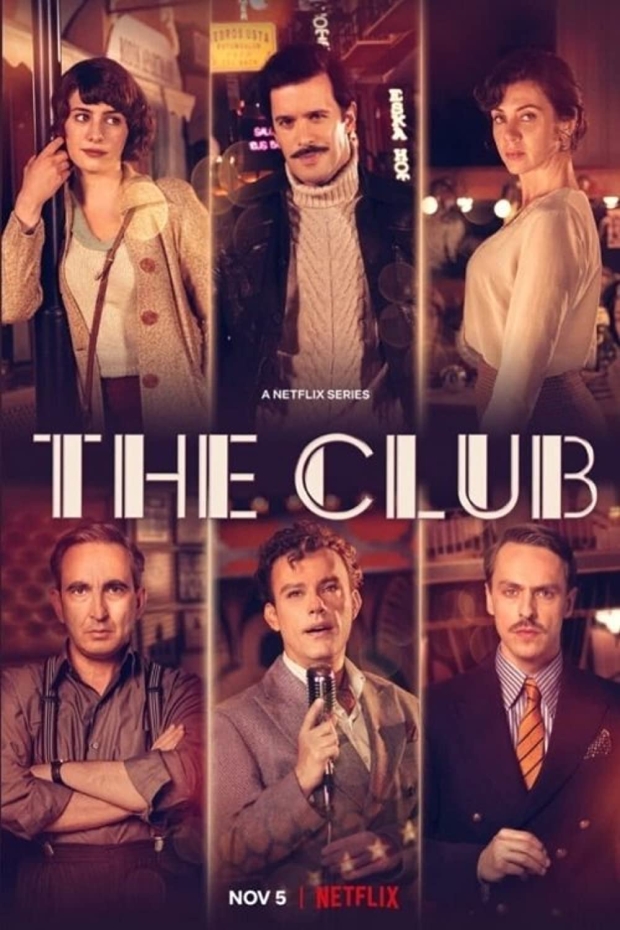

Kulup: Netflix series helps Turkey rediscover its Jewish heritage

It's a Turkish drama that does not involve a crescent-mustached Ottoman sultan, nor does it follow the daily happenings of a family living in a luxurious villa on the shores of the Bosphorus.

Instead The Club (Kulup in Turkish) focuses on Istanbul’s Jewish community in the 1950s. Set in and around Turkey’s most famous street, Istiklal Caddesi, the show is unique in that its list of characters is primarily made up of non-Muslims whose mother tongue is not Turkish - a rarity in depictions of the country’s past.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Instead they speak Ladino, a Judeo-Spanish dialect, brought to the Ottoman Empire after the expulsion of Sephardic Jews from Spain in the late 15th century.

The show is also a throwback to a Turkey where religious minorities made up a far greater proportion of the population.

At the start of the 20th century, just before the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, slightly more than half of Istanbul’s 864,000 residents were non-Muslim citizens. This ratio shifted towards an overwhelmingly Muslim majority from the First World War onwards and the proclamation of the Turkish Republic in 1923.

By the 1950s, a substantial Greek and Jewish minority, among others, remained but discriminatory policies further diminished the total non-Muslim population.

The Club therefore tells a story furnished with memories of a culture that has long since faded away, rich in depictions of lost rituals and the sounds of rarely heard dialects.

“I heard about the show from my mother,” says Ceren Sengul, whose mother is part of Istanbul’s Sephardic Jewish community.

“She sent me a message as soon as she saw the Shabat prayer at the start of the first episode.”

Describing the reaction among the wider community, Sengul says that her grandmother had told her that the show contained scenes that evoked memories of Jewish gatherings in her youth.

‘A beautiful story’

Without giving too much away, the story revolves around the pairing of Matilda and Rasel, members of the Jewish community - the former a middle-aged woman trying to rein in her rebellious daughter.

But what makes a familiar plot vehicle intriguing, particular for fans on social media, are the scenes in the Ladino language.

“I admit hearing Ladino and seeing a life that once was brought tears to my eyes,” wrote Brooklyn College history professor, Louis Fishman, in a tweet.

'The Club will serve as an introduction to Turkish Jewish history and culture'

- Kenan Cruz Cilli, researcher

“Indeed it's a beautiful story as well.”

Others said the show cast light on an aspect of Istanbul long forgotten but still accessible for those wanting to explore it.

“I believe that for many of its viewers, The Club will serve as an introduction to Turkish Jewish history and culture,” says Kenan Cruz Cilli, a postgraduate student and researcher on Turkey’s Jewish community.

“The show did an excellent job portraying Jewish life within the djuderia (Jewish neighbourhood) known as La Kula.”

Centred around Istanbul’s iconic Galata Tower, the neighbourhood still retains several synagogues, as well as Turkey's Jewish Museum, Cilli explained.

“I hope this series inspires more people to go out and explore La Kula, and other Jewish sites in Istanbul and Turkey.”

Wealth tax

But amid the nostalgia for the Jewish Istanbul, which is fondly remembered, is a more sombre subtext.

The series sheds light on a testing period for Istanbul’s non-Muslim communities.

In 1942, with fear of an impending Nazi invasion, the Turkish Republic implemented a “wealth tax”, which was ostensibly aimed at raising money to defend the country.

However, according to the academic Ayhan Aktar, author of the book The Wealth Tax and The Politics of Turkification, the underlying reason for the levy was to nationalise the Turkish economy and reduce the influence of minorities; meaning Greek, Armenian and Jewish citizens.

“The wealth tax is the main reason behind the migration of the majority of the Turkish Jewish population to Israel,” says Ozgur Kaymak, a lecturer and researcher on ethnic and religious minorities in Turkey.

“The interviews I conducted with people who were affected in this period showed that this tax left a deep wound in both the individual and collective memories of non-Muslims communities in Turkey.”

Implementation of the tax was swift and huge amounts had to be paid in cash, within 15 days of the order coming into force.

Some were able to pay on time, others were forced to liquidate assets, such as property and businesses at below-market price. Those who could not come up with the money were forced to take loans or risk seeing their belongings confiscated.

Though later repealed due to international pressure, the policy had a lasting effect on Turkish minorities. According to the 1935 census, 1.98 percent of the Turkish population was made up of non-Muslim minorities, falling to 1.56 percent in 1945 and 1.08 percent in 1955.

Ivo Molinas, editor of Salom, Turkey’s best-known Jewish newspaper, told Middle East Eye that many within his community felt they had no option but to migrate, especially after the establishment of Israel in 1948.

“Why did these people emigrate? Jews in Turkey wanted to start a new life in a place where they would not face discrimination, racism or bigotry.”

The show makes it a point not to shy away from the consequences of such discriminatory measures.

In one scene, the character David, who runs an orphanage, recalls the policies and tells another character considering migration: “I understand why you want to go to Israel. But it has been more than 400 years. This (Turkey) is our homeland.”

And therein lies the show’s didactic undertone, geared towards its primarily Muslim audience; that minorities, such as the Jewish community, have a long history within the country.

Increased interest in Jewish history

The majority of Turkish Jews trace their ancestry to 15th century Spain and Portugal, where after the reconquista, they were given the options of forced conversion to Catholicism, exile or death.

It was the intervention of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II, who dispatched the Ottoman navy to evacuate the Jewish population, that brought thousands of Sephardic Jews to Istanbul and other Turkish territories.

Researcher Ozgur Kaymak explains that despite this history, the show was probably the first time many Turks had encountered words like “Shabat, Ladino, Purim, or wealth tax”.

She adds that even a simple Google search into the subjects addressed in the show could have a positive effect in opening minds.

“The entertainment business has a special magic when it comes to influencing people,” she says.

Already there is evidence that a conversation is happening, with increased talk of the historic treatment of religious minorities on social media platforms and a spike in Google searches for words like “Sephardic” and “wealth tax”.

“Popular culture can be a great stimulant for political change,” says Kenan Cruz Cilli.

“One can hope that discussions on the discriminatory nature of the wealth tax, as well as its deep seated implications will continue to be discussed on both the civil and political levels.

For Ivo Molinas, a show like The Club can play a big role in countering stereotypes about Jewish people.

“Both in Turkish and foreign movies, there are always dark conspiracies around Jewish characters,” he says.

“They always have a huge amount of power; they are rich, cruel and they have evil intentions.

“In this show they are as vulnerable, poor and desperate as every other citizen...this plays an important role in breaking down these evil stereotypes.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.