Iraqi forces chase shadows in the hunt for Islamic State

The outskirts of al-Adhim, a town 120km north of Baghdad, were engulfed in almost complete darkness. It was close to 3am on 21 January, and temperatures were almost freezing.

In the black of the night, a handful of gunmen crept into the headquarters of an Iraqi army brigade in Umm al-Karami village, to the west of al-Adhim. They opened fire and shot 11 soldiers dead.

The attack was "swift and well planned," military commanders who arrived at the scene told Middle East Eye.

'This operation would not have succeeded without the cooperation of someone from inside. These soldiers were given to their killers by hand'

- Senior field military officer

Two of the gunmen had slipped through the main gate, downing four soldiers. The rest approached from the rear, capturing the remaining soldiers and putting bullets in their head one by one.

"This operation would not have succeeded without the cooperation of someone from inside. These soldiers were given to their killers by hand," a senior field military officer told MEE. "It is clear that the attackers knew how many soldiers were inside the headquarters, where they were, when they switched duties, and even their daily habits."

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Before any serious investigations had begun, military and political leaders attributed the attack to a resurgent Islamic State group (IS). But already, there were some puzzling inconsistencies.

Unusually, the attackers left behind a mouthwatering arsenal untouched, seemingly uninterested in the weapons and equipment lying around the base. Similarly, they made no attempt to torch the left-over vehicles, which could have been used subsequently to chase them down. Such behaviour is unknown for well-trained IS militants, as these were alleged to have been.

Nonetheless, the Umm al-Karami attack quickly whipped up growing fear that IS has returned with a vengeance, as it was seen as the latest in a long line of increasingly deadly attacks in Diyala province. It didn't help that 600km away, on the same day, the militant group was staging a deadly jail break in Syria's Hasakah prison.

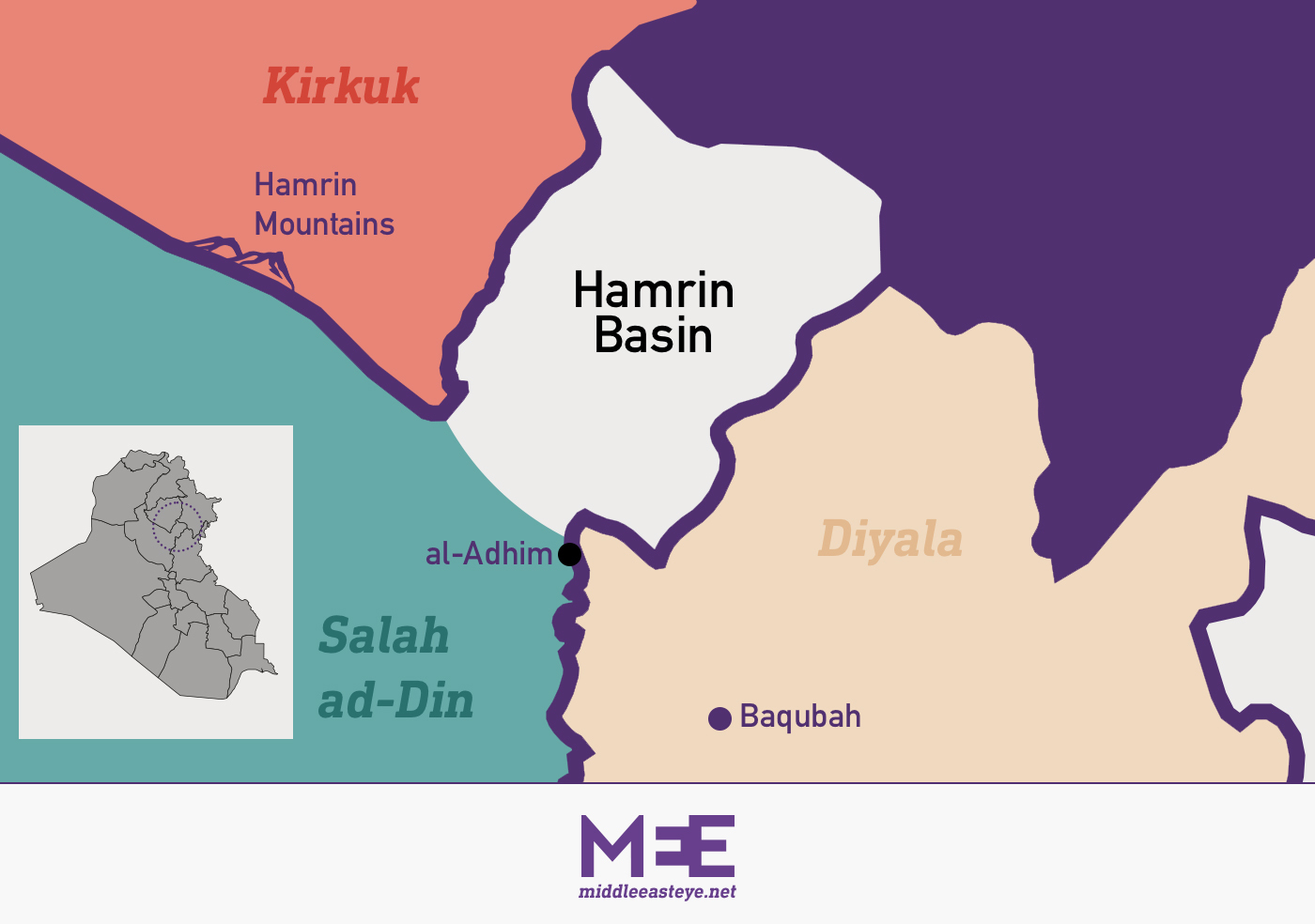

Now Iraqis are left wondering: can IS stage even bigger attacks, and who exactly is in control of the dangerous lands known as the Hamrin Basin?

Safe havens

Since IS was wiped from its urban strongholds in Iraq in 2017, the group's militants have mostly retreated to old sanctuaries scattered in Al Anbar's Western Desert and the Hamrin Basin, which lies to the north of Baqubah, Diyala's capital.

Although the Western Desert was and remains an important haven for the organisation, Iraqi military commanders and observers say the majority of IS fighters have sought refuge in the Hamrin Basin. The area has been one of the largest and most dangerous strongholds of Sunni and Kurdish extremist groups for decades. The Basin's ruggedness and varied terrain provide a network of safe corridors that cut through a series of valleys and hills.

Its location, equally, aids outlaws. The area sits in the land where the provinces of Diyala, Salah al-Din and Kirkuk meet, tying together Iraq's north and west. That makes it "a strategic transportation node" for any armed group or regular military force, a senior Iraqi military commander told MEE.

Whoever controls the Hamrin Basin can separate Baghdad from Iraq's north, including the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region and adjacent areas.

Iraqi military field commanders told MEE that IS militants have largely adopted guerilla tactics. While the group's deficit in human and financial resources has necessitated this strategy, commanders note that it is an effective way of "draining" Iraqi forces, as well as proving IS's existence and potency.

At least 30 attacks targeting Iraqi forces during the past three months have been launched from the Hamrin Basin, sources said. The raid on Umm al-Karami, which lies in a Hamrin Basin valley, was the most recent.

Securing and controlling the Basin is a challenge the Iraqi government has wrestled with since 2005.

"These areas are the most dangerous militarily. It is difficult for our forces to control them, because they are rugged areas that extend for tens of kilometres," a Rapid Response Forces commander, who was deployed to Umm al-Karami after the attack, told MEE.

"Control of such areas requires continuous military operations, constant border monitoring, and a huge intelligence effort."

It doesn't help, he added, that the Iraqi forces deployed in the region are kaleidoscopic. You can find federal soldiers, local police, Kurdish troops and a number of paramilitaries divided along sectarian and ethnic lines. These forces' varied loyalties and objectives make securing the region "an almost impossible task," he complained.

Aisha camp

A huge military operation was launched after the Umm al-Karami attack, with thousands of federal and local forces combing the area in the search for perpetrators. The results were disappointing, commanders participating in the campaign told MEE. Hideouts were discovered - caves and tunnels scattered around the Basin's valleys - but "most of them had been abandoned for a long time," the commander of one regiment told MEE.

"We left our vehicles and walked for more than 10 hours to inspect and clear the area. We did not find anyone, and not a single bullet was fired at us. I bet these havens have not been used by anyone for at least a year."

A key goal of the campaign, which lasted for several days, was reaching Camp Aisha, a fortified base established by al-Qaeda in 2007 and later used by its offshoot, IS.

The camp is in a 2km-long valley in the Hamrin mountains, north of Diyala. Though its location has long been known, Iraqi forces have previously left Camp Aisha alone. The exact reasons for this are unclear, though commanders have argued that there was concern over the risk to life involved in storming the camp. In the end, its capture played out quite differently.

"Finally, we captured Camp Aisha," one of the senior field officers told MEE. "We had to leave our vehicles and go on foot. The terrain here is very rough and the mission is very risky, but finally we arrived. We cleared the entire camp and destroyed the havens we found."

The camp was deserted. In fact, there was no indication that it had been used at any point in recent months, perhaps even years, officers involved in the campaign told MEE.

Hidden in plain sight

There are no official statistics revealing the true number of IS militants, but Iraqi commanders estimate the total is in the hundreds. Islamic State's capabilities pale in comparison to when it was at its peak, when it controlled a third of Syria and Iraq. Yet its militants nonetheless are able to stage deadly and distressing operations from time to time.

The most terrifying of these raids, for both Iraqi forces and civilians, are direct attacks on guard posts and kidnappings. During the past six weeks, local police in Diyala province alone have recorded five kidnappings. Mostly, they targeted local fishermen and visitors from other governorates.

'IS fighters hide among the villagers. During the day you see them as peaceful herders who roam freely, but at night they turn out to be guerillas'

- Iraqi officer

However, the true number of kidnappings targeting soldiers and paramilitary fighters deployed in the area is several times greater than that given publicly, commanders told MEE.

"From time to time, we find the bodies of our soldiers who were kidnapped from here and there, dumped in a valley. They usually target soldiers who leave their units on holiday," a senior field commander told MEE.

"The fact that IS fighters are not in the areas targeted by the military campaign does not mean that they come from the sky. They are among the residents and are watching our movements first hand.”

The militants, commanders believe, are dotted among the picturesque villages scattered across the Hamrin Basin’s hills, plains and valleys. And the villagers within them are believed to be the militants' greatest assets.

Many of them cooperate with the IS fighters, and provide them with shelter, food and information. They do this either out of sympathy or fear, officers and local officials told MEE. Other villages are deserted, abandoned since the battles to retake the area from IS began in late 2015. Militants are able to use the empty homes as hideouts.

"IS fighters hide among the villagers. During the day you see them as peaceful herders who roam freely in the area, but at night they turn out to be guerillas," said an officer serving in northern al-Adhim. "So far, we have not succeeded in stopping them completely. We still cannot distinguish them from the rest of the villagers."

Just another gang

Diyala, Salah al-Din and Kirkuk are the most diverse of all Iraqi provinces, the home to an array of sects and ethnicities. The sectarian and ethnic diversity in these three provinces has turned it into a contested area for the various Iraqi political forces. It is an ideal environment for Sunni, Kurdish, Shia and Turkmen armed groups, all of which are linked to local, regional and major powers, and who carry out operations on demand.

Military field commanders said IS is responsible for no more than 10 percent of the attacks being reported in these three provinces.

"IS is an umbrella," a senior field military commander told MEE.

"In fact, it has become a disguise that everyone takes turns to wear, to carry out operations that serve their agendas."

The area has long been a battleground for gangs competing for influence and resources, he said. Islamic State is just one among many.

"The military leadership in Baghdad always chooses to side with the winner. After each attack, it blames IS instead of looking for the real culprits and holding them accountable," he said. "It is not important that we reveal the identity of the killers and their connections," he added, sarcastically. "The most important thing is that we protect our positions and hide our heads in the sand and move on."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.