The digital effort to save Ankara's Jewish history

The history of the modern Jewish community in Ankara dates back to at least the 15th century, when Jews fleeing persecution in the Iberian Peninsula joined an existing community of Greek-speaking Romaniote Jews in the central Anatolian town.

Located in the Ankara district of Altindag, the Jewish quarter was the heart of this community.

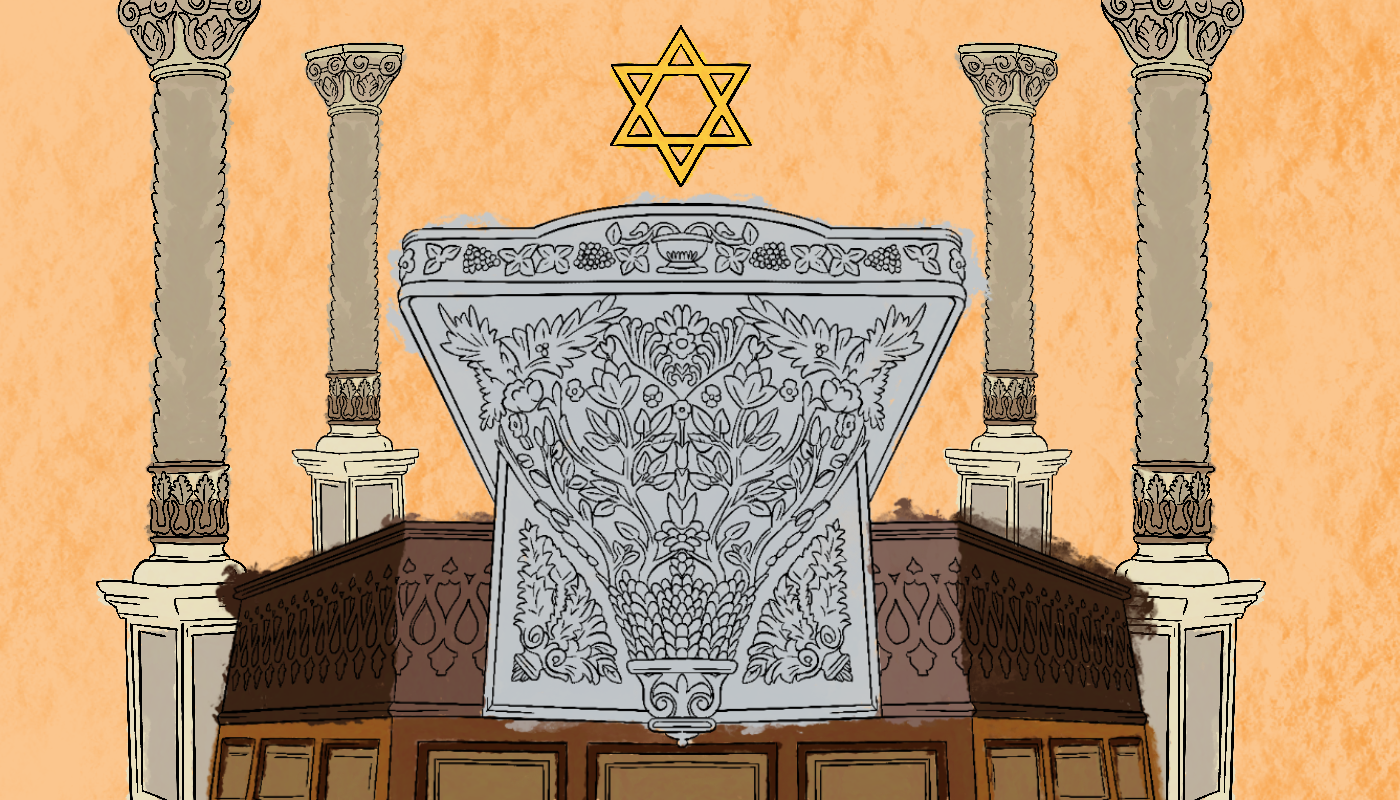

It drew new arrivals throughout the Ottoman period and featured schools, a synagogue, and a beit midrash (Torah study hall).

Today, derelict mansions and an impressive, albeit discrete, synagogue remain standing as a testament to this important aspect of the Turkish capital's history.

As the neighbourhood becomes increasingly run-down, preserving the history of the Jewish community in Ankara has taken on a heightened importance.

To that end, a recently launched digital platform seeks to make sure that the Jewish quarter’s stories are not forgotten.

The initiative, called the Jewish Quarter Ankara Digital Platform (JQA), thoroughly compiles the history of Ankara’s Jewish community, as well as the city's historic Jewish neighbourhood, drawing on academic publications, news articles, cadastral records, personal memoirs, and interviews with former Jewish residents of Ankara.

This rich trove of material can be accessed on the platform, which consists of three separate parts, each focused on highlighting different aspects of the Jewish quarter’s past and present.

“In the section on the ‘Ankara Jewish Community’ it is possible to get information about the deep rooted history of the Jews of Ankara,” says Aysin Zoe Gunes, the designer and coordinator of the project.

“The ‘Archive of The Silence’, on the other hand, contains digital exhibitions… while the ‘Ankara Jewish Quarter’ includes a 3D digital tour of the neighbourhood,” she continues.

“It offers the experience of exploring the Jewish Quarter today with the knowledge of the past.”

Organisers hope the project will expose the little-known history of the Jewish community in Ankara to the wider Turkish public and to others around the world.

The Jewish quarter in the republican era

Ankara underwent tremendous changes following its newfound status as the capital of the Turkish republic in 1923.

The city experienced unprecedented growth, leading to the construction of many new, well-planned neighbourhoods throughout the city.

Modernising reforms during the early republican period also led to the erasure of much of Ankara’s historical identity as a multicultural and multi-religious city.

“I think that Ankara’s portrayal as an early republican city and its recognition in this way is an injustice done to Ankara,” says Yavuz Iscen, a researcher and consultant to the Ankara Jewish Quarter project.

“In the first years of its establishment, the republican administration tended to ignore the city’s past or to interpret it in its own way, in line with the discourse that ‘we created a modern city from a steppe town’,” he goes on.

In this context, beginning in the 1930s, many of the Jewish residents of the old Jewish quarter began to move to the newer neighbourhoods of Ankara. This migratory shift within the city was the starting point of the Jewish quarter’s slow yet steady decline.

The Jews who remained in the old quarter in this period were mostly the impoverished members of the community who could not afford to move to the newer neighbourhoods of modern Ankara.

Policies such as the 1942 wealth tax levied discriminatorily and disproportionately on non-Muslims, also led to the decline of Jewish life in Ankara as many Jewish properties were expropriated by the Turkish state.

The final blow to Jewish life in the quarter was dealt in 1948, with the foundation of the state of Israel.

Prospects of a better life in the burgeoning Jewish state prompted almost all of the neighbourhood’s impoverished Jews to migrate.

One elderly Jewish woman named Sara stood defiant, choosing to remain in the neighbourhood of her birth up until the 1980s.

For decades, she was the sole Jewish resident of the old Jewish quarter.

Sara, who later passed away at an old people’s home in Istanbul, remained in the Jewish quarter until her old age made that impossible. Her unique story is one of many that the Jewish Quarter Ankara Digital Platform brings to light.

An uncertain future

In more recent times, the Jewish quarter of Ankara has faced continued degradation, giving the Jewish Quarter Ankara project a sense of increased relevance.

Many of the surviving historic structures in the neighbourhood are in dire conditions today, with complicated disputes in terms of ownership adding to a complex set of bureaucratic obstacles that impede their conservation.

“The neighbourhood has a great importance in terms of social, cultural and architectural history, and these unique features are often lost due to fires or desolateness,” says Aysin Zoe Gunes.

“It is obvious that the buildings in the neighbourhood will fall into ruin and become destroyed if a detailed and healthy conservation plan is not implemented,” she adds.

One major force that frequently spearheads conservation projects in Turkey is the country’s massive tourism industry, which attracts tens of millions of visitors every year.

However, tourism and the changes that come with it can pose a different threat to neighbourhoods such as Ankara’s Jewish quarter.

Often described as a double-edged sword, tourism can ensure the investment of money and the implementation of preservation plans, whilst simultaneously resulting in gentrification and the accelerated loss of local atmosphere.

“To be frank, I don’t think tourism, whose main purpose is to make a profit, will take the conservation of the neighbourhood seriously,” says Yavuz Iscen.

“The deplorable physical and cultural situation of places that opened to tourism with the promise of protection, both in Turkey and in Ankara, pushes me to think in this way.”

Nonetheless, Iscen points to various actions that can be taken in the near future to protect the neighbourhood and preserve its status as an important site of memory in Ankara.

“One of the neighbourhood mansions can be reevaluated as a museum, the synagogue can be saved from its hidden appearance, and efforts can be made to ensure cultural continuity,” he suggests.

As the Jewish community of Ankara numbers around 35 members today, one thing that is certain is that any future preservation project in the Jewish quarter will have to be carried out in collaboration with members of the wider, non-Jewish public.

In this sense, the Jewish Quarter Ankara Digital Platform project is exemplary, in that many of the team’s members, consultants, and researchers come from non-Jewish backgrounds.

“Armenians, Greeks and Jews are the indigenous public of Ankara who have been settled here since pre-Ottoman times,” says Iscen.

“All these experiences form a part of the cultural richness of the city. Being aware of and owning this richness does not diminish us, on the contrary, it contributes a lot.

"I consider the Ankara Jewish Quarter Digital Platform Project an important step in seeing and feeling this cultural richness.”

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.