Inside Mexico's deep and unexpected legacy of Iranians

Along the azure waters of Acapulco Bay sits a white house decorated with Arabesque arches. Locals call it La Casa del Sha, the Shah's House, a reference to the Shah of Iran, who lived in Mexico following his overthrow in 1979.

His former home in reality stood beside the Arabesque villa. It has since been demolished, but his memory lives on in Villa del Sha, a luxury complex that replaced it. After he fled Iran, Mexico was one of the few countries that offered the shah temporary refuge amid US pressure to let him in. It wasn't totally unfamiliar for him; in 1975, he had embarked on Iran's first official state visit to the Latin American country.

Mexico may seem an unlikely place to stumble upon reminders of Iran's last monarch, but traces of his brief stay can be found in the homes, restaurants and hotels he frequented, especially in Cuernavaca, a resort town south of Mexico City where he was based. Two Mexican sisters, twins, even claim to be his children.

While the shah may be Mexico's most famous immigrant from Iran, others have also become household names, such as actress Iran Eory and dancer Armen Ohanian.

Iranian migration has left a mark on Mexican culture and history that belies its sporadic nature. In recent decades, increasing numbers of Iranians have made their way here, making a home a world away in a country that many say reminds them of their homeland.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Iranian presence in Mexico

The Iranian presence in Mexico dates back centuries to when Mexico City was a thriving capital in Spain's empire. Ships arrived regularly on Manila galleons from the Philippines, bringing luxury goods from Asia in return for Mexican silver. Thousands of people from across Asia crossed to Latin America on these boats.

Among them was Don Pedro de Zarate, a merchant from Isfahan, Iran, who made his way to Mexico City in the 1720s. He was part of a small community of New Julfa Armenians living in the La Merced neighborhood. Accused of being a heretic by the Spanish Inquisition, we only know of their existence because of de Zarate's testimony to the inquisition in Mexico City in 1730.

It is unclear if de Zarate left any ancestors, but his legacy as a merchant lives on among Iranians in Mexico City.

One of the main squares of Polanco, the Mexican capital's answer to Beverly Hills, is crowned by a large sign reading Tapetes Teheran (Tehran Carpets), marking a business founded by the Bahador family more than 20 years ago. Originally from Iran, they moved to Canada before settling in the capital, where members of their family had come before the 1979 revolution.

The carpet business is where Iranians are most visible today, running several shops across the city. In early 2022, the capital's National Museum of Cultures even hosted an exhibit on Iranian rugs, with pieces donated by the Bahadors.

Among the first Persian carpet merchants in Mexico were the Odabashians, who set up shop in 1923. The family, who were Armenians from Erzurum and fled the genocide in the Ottoman Empire, were famous for selling Persian carpets.

Iranian immigration to Mexico

The modern wave of Iranian immigration started in the mid-20th century. Amineh Parvaz's grandparents were among them.

"They came looking for a better life, and, after having stopped in many countries, they settled in Mexico," she told MEE. "My father always loved Mexico because it took him in when he was young."

Parvaz, whose mother is Mexican, grew up around Mexico's Arab community. She felt connected to her Iranian heritage, learning Persian and even travelling to Iran.

Parvaz estimated that around 3,000 Iranians live across Mexico, with around 200 in the capital and the rest spread across the country.

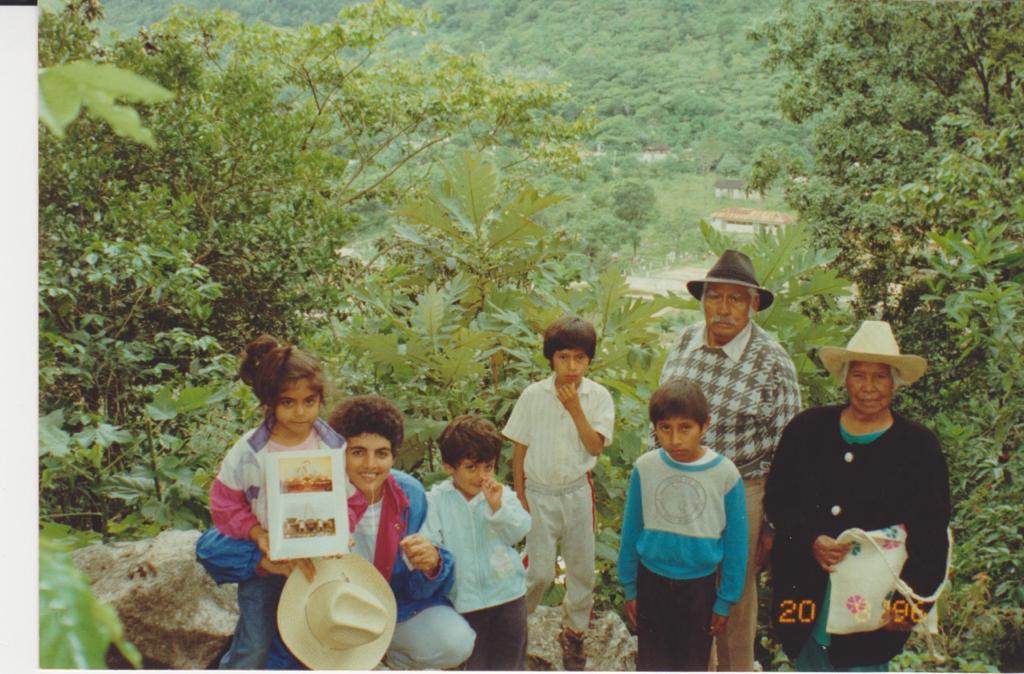

Many came following Iran's 1979 revolution. Among them was Badi Zarate-Khalili's mother. Born in Mazandaran on the Caspian Sea coast, she was raised in a Baha'i family that feared persecution amid Iran's political turmoil.

"She arrived in Colima and settled with a Mexican Baha'i family there," Zarate-Khalili told MEE. She chose Mexico because her sister had moved there prior to 1979.

His mother worked as a housekeeper for several years and eventually studied medicine and became active in social justice issues. On a peace delegation to El Salvador in the 1980s, amidst a civil war there, she met Zarate-Khalili's father, a Mexican from Oaxaca with indigenous heritage.

"He fell in love with her and proposed, but she said no at first," Zarate-Khalili said. "He went and learned Persian and came back a year later and asked her again, this time in Persian. That time she said yes."

Zarate-Khalili grew up speaking Persian at home. His mother cooked Iranian food with Mexican ingredients, getting used to new flavours and adapting them to her favourite dishes.

"She always says that Mazandaran shares a lot with the west of Mexico. They're both semi-tropical and produce lots of fruits and vegetables."

Zarate-Khalili has worked on migration issues and is currently employed at Mexico's Ministry of Equality. He says his mother's experience of displacement informed his path.

"My mother became more Mexican over time, and my dad became more Iranian," he said. "She is proud of being Iranian and never lived in the melancholy of losing her home. She gave her life for the people here, and dedicated herself to making social change in Mexico."

A refuge for intellectuals and artists

Mexico has long provided a refuge for persecuted intellectuals, including Spanish leftists fleeing the 1930s fascist takeover, Russians like Leon Trotsky escaping Stalinist repression, and Americans such as Conlon Nancorrow, who faced persecution as a Communist Party member.

Mohsen Emadi is a poet who fled Iran after the 2009 Green Movement protests and ensuing government crackdown. In 2012, he arrived in Mexico, a country that had fascinated him for years.

"I was always interested in Latin America because of its history, especially its leftist politics. I had read a lot about the Mexican and Cuban Revolutions. I also translated Mexican poetry into Persian," he told MEE, noting that he loved the works of authors Juan Rulfo and Octavio Paz.

Many Iranians note that Mexico City feels very familiar, resembling Tehran in many ways.

Bani Khoshnoudi is an Iranian-American filmmaker whose family left Iran in 1979. Raised in Austin, Texas, she grew up surrounded by Mexican culture.

"When I arrived in Mexico, it felt like a parallel to Iran I'd never experienced before. The city and people reminded me of Iran," she said.

'When I arrived in Mexico, it felt like a parallel to Iran I'd never experienced before. The city and people reminded me of Iran'

- Bani Khoshnoudi, filmmaker

"In the 2000s, I went to Iran often but always agonized over censorship and the political situation," she told MEE. Khoshnoudi filmed a documentary during the 2009 elections and left the country amid the ensuing repression, when thousands were arrested. She said that being in Mexico after that experience offered her a space of "healing".

Khoshnoudi's most recent film, Fireflies, inspired by her experiences in Tehran, follows a queer Iranian refugee in the Mexican port Veracruz.

Mexico has also provided a place for Iranian artists to start anew. Classical Persian musician Mehdi Moshtagh's journey to Mexico began after a chance encounter on a bus in the Iranian desert, when group of Mexican tourists took an interest in the setar he carried with him.

"I invited them to a music class I was teaching, and we became friends. I gave them a few of my albums as a present," he said. A few years later, Moshtagh was invited to perform at the Ollin Kan music festival in Mexico City.

"Mexico was totally new for me. I knew nothing about it. In Mexico many people think that in Iran everyone rides camels; in Iran we had a similar view about Mexico," he said, laughing.

His music became so popular that he was able to fully crowdfund the first album of Persian classical music recorded in Mexico, entitled Tarde y Lejos (Far and Late), a nod to the fact that he began working on it in Iran but finished it years later in his new home.

"The fact that the people of Mexico supported it and made it happen was so gratifying for me,” he said.

His most recent venture, Perxico, brings together Persian and Mexican instruments, rhythms, and musicians to produce a fusion that embodies the identity he's created.

"From the beginning, I missed Iran. But after a few years, I started to realise that when I went to Iran I missed Mexico, too. This country and its people became a part of me," a fact that is reflected in the album.

This article is part of a series. To find out more about other Middle Eastern communities around the world, stay tuned for the next piece, due to be published next week.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.