Why the Middle East is witnessing a rare moment of regional de-escalation

For a long time, the Middle East region has been one of the most volatile regions in the world.

Instability, conflicts, rivalry, and struggles among its key regional heavyweights have been the norm to the extent that one could not remember the last time when all these players agreed on something.

In a surprisingly contradicting manner, the Middle East is currently witnessing an unprecedented pace of reconciliation among the regional powers

However, in a surprisingly contradicting manner, the Middle East is currently witnessing a rare moment of regional de-escalation and an unprecedented pace of reconciliation among the regional powers. Several key players have been reaching out to each other to normalise relations and open a new page. Business, security, and diplomacy have been at the core of the talks between these countries’ top leaders and key decision-makers.

The process started with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) reaching out to Iran at the end of 2020 and Saudi Arabia reaching out to Qatar at the beginning of 2021. Afterward, intensive diplomatic engagements kicked off between Egypt and Qatar, Turkey and Egypt, UAE and Turkey, Turkey and Israel, Saudi Arabia and Iran, and Turkey and Saudi Arabia.

In most cases, the engagement between the intelligence communities of the adversaries ensured an apolitical and professional environment for the politicians to communicate in order to work out their differences. Likewise, business, trade and investments provided strong and solid incentives for the involved parties to seek common ground and achieve a win-win situation.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Comprehensive review

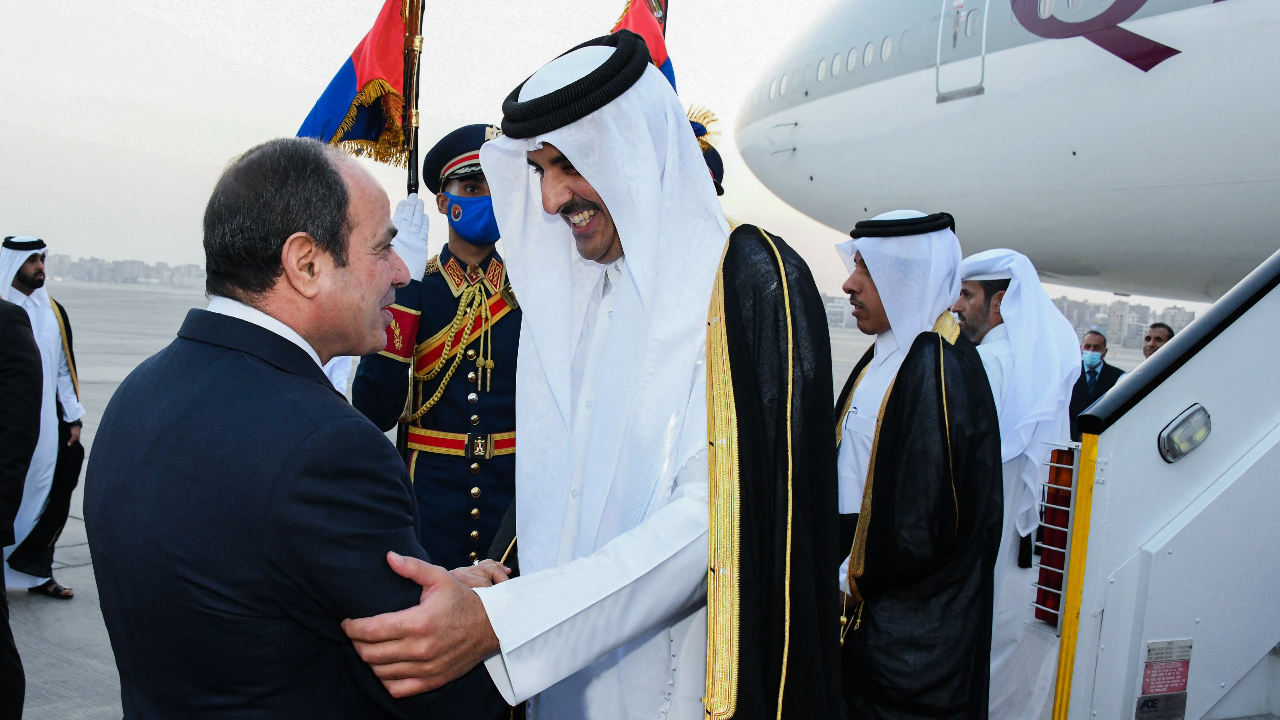

In January 2021, Egypt resumed its diplomatic relations with Qatar after years of tensions. The top diplomats of the two countries exchanged visits. They established a follow-up committee to settle issues of bilateral concern and a high joint committee to boost cooperation between the two capitals.

Egypt’s President Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi met Qatar’s emir three times, in Baghdad in August 2021, Beijing in November 2021 and in Cairo in June. As ties improved, Doha pledged in March to invest $5bn in the Egyptian economy in the coming few years, which will add to the billions of dollars it has already invested.

As for Turkey and Egypt, their rapprochement started officially in May 2021. Delegations from the two countries led by deputy foreign ministers conducted two rounds of exploratory talks in 2021, one in Cairo in May and the other in Ankara in September. They addressed bilateral issues and a number of regional issues, particularly the situation in Libya, Syria and Iraq, and the need to achieve peace and security in the Eastern Mediterranean region.

The normalisation has been going forward slowly but steadily. In April, Turkey’s foreign minister did not rule out the reciprocal appointment of ambassadors with Cairo and a meeting at the foreign ministerial level. Turkish Minister of Treasury and Finance Nureddin Nebati visited Egypt in June, the first by a Turkish minister to Cairo in nine years.

In 2021, the two regional rivalries, Saudi Arabia and Iran, sat down together for the first time in years following an Iraqi effort to facilitate talks between them in Baghdad. Riyadh cut off diplomatic ties with Iran in 2016 after the storming of its embassy in Tehran.

The first round of the exploratory talks between them kicked off in September. Despite the short-lived setback in March when Iran announced the suspension of talks, officials of the two countries conducted a fifth round of talks in April.

Security issues, Yemen, and the reopening of their embassies were among the topics discussed. While Tehran has stressed the importance of resuming diplomatic relations, Riyadh asserted that it wants to see more practical actions from Tehran first.

The rapprochement between the UAE and Turkey was surprisingly quick, given the tense state of relations in the last decade or so. Approaching each other with a clear and direct agenda, mostly revolving around the mutual benefits of boosting trade, investment, and business in a win-win situation, was determinant.

In November, Mohammad bin Zayed (MbZ), Abu Dhabi’s crown prince at the time and the de facto ruler of the UAE, paid a visit to Turkey, the first of its kind in nine years. His visit was preceded by a visit of the UAE’s national security advisor Sheikh Tahnoun bin Zayed to Ankara in August 2021. Turkey’s president reciprocated by visiting Abu Dhabi in February. A lavish reception was arranged for him.

These visits resulted in a number of agreements, memorandums of understanding, and deals that inaugurated the opening of a new page between the two capitals.

When it comes to Turkey and Israel, Israel’s President Isaac Herzog paid a landmark visit to Ankara in March this year, the first of its kind for an Israeli president in 15 years. Several developments prepared the ground for this visit, including a rare phone call between the two presidents in July 2021, a secret visit of Israel’s Foreign Ministry Director-General Alon Ushpiz, to Ankara in January, and a delegation of senior Turkish officials flying to Tel Aviv in February.

The involvement of the Israeli government means that rebuilding bilateral relations must be done in a measured and cautious way. However, during the last year, intelligence cooperation took the upper hand between the two sides.

Moreover, the two parties have been mulling over the possibility of carrying Israel’s gas to Europe via Turkey, which – if realised – will be a game-changer in the Eastern Mediterranean. To build on the visit of the Israeli president and consolidate the rapprochement, Turkey’s foreign minister visited Israel in May, in parallel to visiting Palestine.

As for Saudi Arabia and Turkey, although the rapprochement between the two countries started as early as October 2020, when King Salman and President Erdogan exchanged several messages and phone calls, the normalisation process stalled on certain issues for approximately a year.

Two factors contributed to this situation: Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman’s personal position on the murder of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi at his country’s consulate in Istanbul in October 2018, and the lack of an adequate formula to reset the bilateral relations following this incident.

Finally, the two parties managed to achieve a breakthrough, which resulted in the visit of President Erdogan to Riyadh in April this year and his meetings with King Salman and the crown prince.

In reciprocation, Mohammed bin Salman visited Ankara in June. Despite the apparent progress, no apparent economic, political, or security agenda was announced till that time.

A suitable environment

These normalisation processes could not have happened without certain developments on the international, regional, and sub-regional levels. These developments set the scene for regional de-escalation, creating a suitable environment and common ground for the conflicting parties to sit down together, discuss shared interests, reconcile, and normalise their relations in an unprecedented manner.

The defeat of Donald Trump in the US presidential elections in November 2020 had a tremendous impact on the nature of the regional dynamics at play since 2021.

Countries that depended for so long on Trump as a transactional president to prioritise and enforce ideological, divisive, and confrontational regional agendas suddenly found themselves in an unfavorable position following the triumph of Joe Biden in the US presidential elections.

A new president in the White House meant a new game to play in the region. In particular, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt followed the same path after failing to realise their regional agenda. Israel lost the investment in Kushner’s project dubbed "The Deal of the Century".

Additionally, Tel Aviv was already undergoing an internal change with the defeat of Israel’s longest-serving prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, who had stayed in power for 15 years.

As for Turkey, it felt the need to avoid being overstretched regionally. Therefore, it balanced its hard power with soft power to cash in on its successful military activism in Syria, Iraq, Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh, and the Eastern Mediterranean, in terms of political and economic gains.

The Al-Ula declaration on 5 January 2021 was the first major outcome of Biden’s ascendance to the White House. The declaration stemmed originally from a bilateral understanding between Saudi Arabia and Qatar. The agreement ended the blockade imposed by the Saudi-led bloc comprised of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt on Doha and opened a new page between Qatar and its neighbors.

As a result, the al-Ula agreement accelerated the reconciliation process within the GCC and triggered a chain reaction of several regional diplomatic engagements that opened the door for reconciliatory initiatives.

Although the UAE and Egypt were not initially happy with the agreement due to the fact that Saudi Arabia did not consult with them on it, they saw it as an opportunity to follow relatively flexible agendas. This approach helped them diversify their regional relations, prioritise their key issues, and advance their own interests.

Accordingly, Egypt reached out to Qatar, and the UAE reached out to Turkey. Likewise, the al-Ula agreement allowed Ankara to strengthen its relations with the small Gulf countries and pursue normalisation of relations with Egypt and Saudi Arabia.

In addition to these two major developments, several other critical factors contributed to the new regional dynamics at play, thus creating a rare moment of unprecedented de-escalation and regional reconciliations.

These include: the end of the 2011 Arab uprising era, Washington's de-prioritising of the region and decreasing its security commitments to several countries, including Gulf countries; the Covid-19 pandemic, the renewed Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) negotiations with Iran; and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The continuation of the American re-focus and shift of resources towards China prompted the GCC states to accelerate their diversification and hedging strategies. As a result, countries like Turkey, Israel, and Iran gained more importance in this situation.

The power fatigue resulting from following highly contrasting geopolitical and ideological agendas and the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in the post-2011 era encouraged the conflicting regional players to follow pragmatic behaviour and prioritise the economy, business, trade, and interest-based agendas rather than ideological ones.

As the pandemic began to recede in 2021-2022, these regional players were in a good position to approach each other with a pragmatic/economic mindset that aimed to compensate for the devastating economic and financial losses caused by the pandemic. This was evident in the case of Egypt-Qatar, UAE-Turkey, Turkey-Egypt, and the Israel-Turkey rapprochement efforts.

The Russian war against Ukraine gave more importance to the Eastern Mediterranean region and its oil and gas resources, thus creating a positive atmosphere for countries to reach a common ground for a win-win situation, especially in the case of Turkey, Israel, and Egypt.

Challenges ahead

Despite the positive impact of this unprecedented de-escalation in the region, there are questions regarding the sustainability of the reconciliation and the resilience of the normalisation processes.

Moreover, it is not quite clear yet whether this is a temporary situation driven by the tactical calculations of some of the countries involved or a newly emerging norm and trend based on strategic calculations. Regardless, several challenges will soon test this new phenomenon in the Middle East.

The regional and international dynamics that have led to this rare moment of de-escalation and reconciliation among the different regional players, in particular, are not constant and subject to sudden changes.

The highly volatile situation means possible shifts in these dynamics in the near future cannot be ruled out and may thus negatively affect the process resulting in a regression.

Additionally, one obvious characteristic of the current normalisation processes is that they are highly based on the nature of the personal relations between the decision-makers of the countries in question. While this might be good when it comes to surpassing bureaucratic hurdles that may cause long delays in the normalisation of relations, it may indicate weak institutional relations.

An under-institutionalised relation makes the reconciliation between the relevant states fragile and highly vulnerable vis-a-vis political fluctuations in the future. Furthermore, a dramatic change at the top level in any of the primary regional players might trigger different kinds of intra-regional relations.

Several other factors are worthy of closer observation in the near future and might test the current regional normalisation and de-escalation moment. These factors include;

Firstly, the 2024 US presidential elections are very critical and determinant to the region as they might bring another transactional Trump-like president to office. A poll conducted by Associated Press (AP) in May found that President Joe Biden’s approval rating has hit a new low, with only 39 percent approving his job performance.

While AP noted that Republicans’ disapproval of Biden has remained steady –less than one in 10 GOP respondents approve of him – his popularity among Democrats has declined throughout his presidency.

While no US president has served two non-consecutive terms in US history – with the exception of President Grover Cleveland, who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and again from 1893 to 1897 - there are strong speculations on the prospects of Trump coming back in 2024.

The idea that Trump or a Trump-like president may come in 2024 could potentially encourage some regional states, particularly the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Israel and Egypt, to follow the same old risky policies.

Turkish elections

Second, the 2023 presidential elections in Turkey. This election is of high importance to the Turks and the region.

Several regional and international powers have been betting on an internal change in Ankara to reshape the regional dynamics in their favour. A scenario in which a government subservient to the West arises will dramatically change Ankara’s regional role and the nature of its relations with several regional countries.

The main opposition party, the CHP, has pledged to kick Syrian refugees out of Turkey and resume relations with the Assad regime. Similar trends can be expected towards different issues and different governments. A reversal of Turkish foreign policy and less diplomatic, economic, and military engagement in the Middle East might be expected. If realised, this scenario would also impact intra-regional relations.

The third is the fate of the 2015 JCPOA nuclear deal between the US and Iran. Negotiations between the Biden administration and the Iranian government to reactivate the deal have been going on for some time.

Several regional countries, particularly Israel and Saudi Arabia, objected to the original deal on the grounds that it would not completely prevent Tehran from producing a nuclear weapon. They also communicated that they would like to block Iran’s missile programme and force the Iranian regime to change its regional behaviour and end its destabilising activities.

Reactivating the same old deal will empower Iran, prompting it to continue its expansionist agenda, which will force Iran’s regional rivals to adopt confrontational policies to counter it. However, the “no deal” scenario is no less dangerous as Iran will likely move closer to producing a nuclear bomb.

This scenario will trigger a nuclear arms race. In both cases, the outcome of the negotiations might reshape the alliances in the region based on the position vis-a-vis Iran.

The Ukraine war effect

Fourth is the emerging food insecurity in the Middle East. In 2019, Russia and Ukraine exported more than 25 percent of the world’s wheat. Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, as well as sanctions against Russia, are disrupting the exports of wheat, grain, corn, and other essential food sources, causing their prices to skyrocket globally.

A second wave of Arab uprisings might force regional players to reconfigure their alliances based on the security of the regimes

Several Arab countries, as well as Israel and Turkey, depend on importing wheat from Russia and Ukraine. Egypt, the world’s largest importer of wheat, depends on Moscow and Kyiv to secure more than 70 percent of its local demand.

Besides Egypt, several Arab countries are severely exposed. If the war is set to prolong, then one should not rule out that a looming food crisis coupled with skyrocketing food prices would trigger uprisings.

This scenario will have political, economic, and security implications. A second wave of Arab uprisings might force regional players to reconfigure their alliances based on the security of the regimes.

Fifth, spoilers and developments in the Eastern Mediterranean. Russia’s weaponising of energy during its war against Ukraine has put Europe at the mercy of Moscow. This situation created an urgent interest in Europe in finding alternative energy sources to meet demand, reduce its dependence on Russian gas, and manage the risk exposure vis-a-vis Moscow.

One untapped source of gas lies in the Eastern Mediterranean basin. Considering the regional de-escalation, the US and some European countries have been signaling the possibility of utilising the hydrocarbon resources of the region.

Utilising the untapped resources of the Eastern Mediterranean and resolving the conflicts between the different players would require taking into account Turkey’s holistic approach on the issue as well as a pipeline that would extend from Israel to Turkey instead of the unfeasible EastMed pipeline from Israel to Greece via Crete, passing through waters claimed by Ankara.

Despite the very positive regional atmosphere resulting from the normalisation processes, it is hard to anticipate whether some of the relevant players are charting this new path out of genuine desire, or they are just being pragmatic

Not content with these developments and with the fact that its major regional partners – the UAE, Israel, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia – have been normalising their relations with Turkey, Greece has emerged as a spoiler.

It is actively working to undermine the de-escalation environment and drag other players, such as the US, into its own problems. If this behaviour continues, it might negatively impact the region and seriously test some of the reconciliation and normalisation processes.

Keeping the momentum

Despite the very positive regional atmosphere resulting from the normalisation processes, it is hard to anticipate whether some of the relevant players are charting this new path out of genuine desire, or they are just being pragmatic, putting their sword in their sheath, lying low, and waiting for the right moment to return to their old policies.

Having said this, if there is a genuine will to turn the de-escalation moment into a sustainable situation, then we should see key regional countries taking at least some of these following measures in the near future.

It is quite vital that the involved parties establish a mechanism capable of containing/solving the problems that might arise in the future

First, prioritising the economic aspect of bilateral relations. The economic space is a de-politicised space by nature, which can easily help establish a win-win formula for the involved parties. Building on economic interests will cement the reconciliation processes and provide it with real and tangible gains for all parties.

Although rentier states might not be so interested in such benefits, the post-Covid-19 pandemic era, the Russian war against Ukraine, and the desire to diversify the economy compels these parties to seriously consider the economic dimension.

Second, identifying areas of common interests in other domains such as security and politics. Then building on these while trying to maintain a separation between politics, economics, and security in times of tension to avoid cutting all ties at once. This way will guarantee minimum damages and enable the parties to keep the communication open on other non-conflicting issues.

Third, engaging in a constructive discussion on the areas of difference between the major regional powers. In this sense, it is vital that the involved parties establish a mechanism capable of containing/solving the problems that might arise in the future.

Additionally, aiming to keep intelligence channels open and working. Security is important to everyone. Due to their geographical position, and feelings of insecurity, some countries tend to prioritise security relations. Keeping an open channel will not only deepen the cooperation on security issues but also might help facilitate the way to discussing some unresolved political issues.

The absence of these measures will signal weak reconciliation and normalisation processes and will make them extremely vulnerable to the aforementioned challenges that are expected to test the current regional configurations sooner or later.

This article was first published by Insight Turkey website.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.