How Lula's victory could end Brazil's global isolation

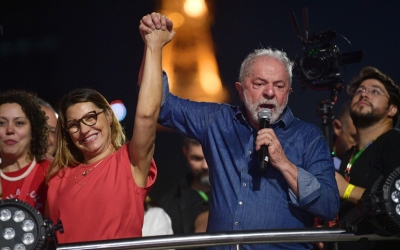

The dust has settled in Brazil, and even if President Jair Bolsonaro and his most radical supporters still won’t admit it, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has won the election. While the ballot was closer than his supporters might have liked - 50.9 percent to 49.1 percent - Lula still won by more than two million votes, despite reports of voter suppression by pro-Bolsonaro forces and the outgoing president’s recent multibillion-dollar spending spree aimed at buying votes.

While protests and road blockades calling for a military coup were still ongoing this week, their numbers were gradually dwindling. Regardless, the sight of thousands of Brazilians pushing for a military coup, with some protesters reportedly performing a Nazi salute to a rendition of the country’s national anthem, has been disturbing, to say the least.

Bolsonaro and his supporters have somewhat relished their pariah status, breaking all diplomatic norms

Almost as disturbing has been the tacit or explicit support for these anti-democratic protests by police. Frustrated with their reluctance to act, members of the public, including groups of football fans, have taken it upon themselves to clear the blockades. The prospect of a successful coup grows more unlikely by the day, as Bolsonaro’s powerful allies have accepted the election results and are seeking to begin the process of an orderly transition.

But what does Lula’s victory mean for the rest of the world? After results were announced on Sunday evening, world leaders from China to the US to Russia swiftly offered their congratulations to the incoming president. Under Bolsonaro, Brazil has gone from a respected international actor known for its commitment to multilateralism, to a pariah state shunned from important summits. Brazil has never been more isolated in its modern history.

Bolsonaro and his supporters have somewhat relished their pariah status, breaking all diplomatic norms by involving themselves as openly partisan actors in American politics, such as by supporting former US President Donald Trump’s challenges to the 2020 election results. Bolsonaro’s fallings-out with world leaders have been very public, such as his row with French President Emmanuel Macron over an Amazon aid package.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Truculent foreign policy

Perhaps nowhere was Bolsonaro’s aggressively truculent foreign policy more evident than in the Middle East. Brazil enjoys strong cultural and historical ties to the region, housing a massive diaspora Arab population of more than 11 million people. Lebanese culture in particular has become part of Brazil’s national identity, from food to music, with the Lebanese community in Brazil today estimated at between seven and 10 million people. Former President Michel Temer is of Lebanese ancestry, as are other prominent politicians.

Since the start of the Syrian war, there has been a new wave of immigration from the region, with Syrian restaurants becoming a part of Sao Paulo’s streetscape. Around 70,000 Palestinian refugees also live in Brazil, with the Palestinian flag and struggle constituting a standard part of left-wing politics.

In 2010, under Lula’s past presidency, Brazil recognised Palestinian independence. Lula proved a reliable ally of the Palestinian cause, becoming the first head of the Brazilian state to visit Palestine. This continued under his successor, Dilma Rousseff, whose government condemned Israel’s offensive in Gaza in 2014 and rejected settler leader Dani Dayan’s nomination as ambassador for Israel.

One of the few countries where Bolsonaro found international support was Israel. In recent years, the Brazilian far right - in large part due to the rise of evangelical Christianity - has embraced Zionism as both a symbol and a cause. The Israeli flag is now a standard part of the Bolsonarista aesthetic. Bolsonaro’s wife, Michelle, cast her vote on election day wearing an Israeli flag T-shirt. Bolsonaro himself even once stated: “My heart is green, yellow, blue and white”, referencing the colours of the Brazilian and Israeli flags.

A welcome change

As journalist Eman Abusidu noted in Middle East Monitor, under Bolsonaro, Brazil became Israel’s “new best friend”. Bolsonaro had even vowed to move Brazil’s embassy to Jerusalem, although he never delivered on that promise.

After Bolsonaro’s election victory in 2018, a senior diplomatic source told Haaretz that “Brazil will now be coloured in blue and white”. Bolsonaro made an official visit to Israel shortly after taking office, and Brazil became one of the few states that would defend Israel at the UN.

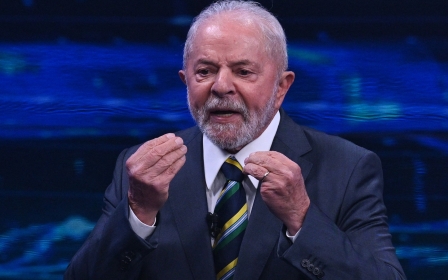

Lula’s return to power will represent Brazil’s return to the world. Lula had left office as one of the most popular elected leaders in history, and was so well-regarded that he was famously referred to by former US President Barack Obama as “the man”. During the election campaign, he frequently referenced his role in managing the Iran nuclear file and the increased role Brazil played in Africa, although it’s not clear whether these issues played any significant role in getting out the vote.

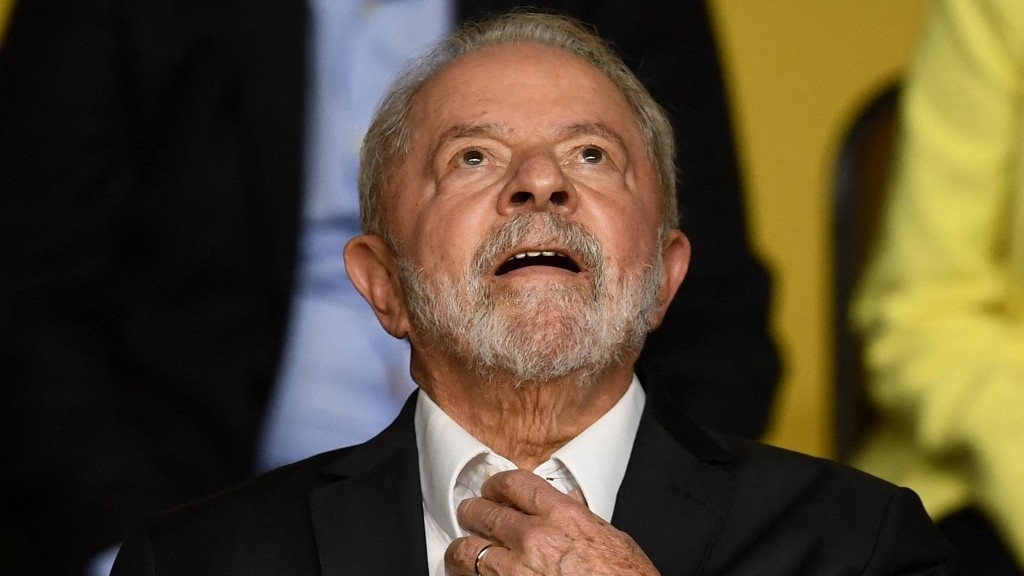

Lula has signalled that he will recommit Brazil to honouring human rights, both at home and abroad, and protecting the environment. After Bolsonaro’s many attacks on LGBTQ+ rights, Black Brazilians and Indigenous people, and his systemic undermining of any attempts to protect the Amazon from deforestation, this is most welcome.

Lula will seek to establish Brazil as an intermediary in international negotiations, recommit to multilateralism, and undo the damage inflicted by his predecessor - but the real challenge will be governance at home. Meanwhile, the world can at least rejoice over Brazil escaping its self-inflicted international isolation through the rejection of a far-right leader at the ballot box.

Brazil is also a favourite for the Qatar World Cup, which starts this month - and a sixth cup would mark a good start for Lula’s presidency.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.